About this course:

This module provides an overview of skin cancer, focusing on the most common types, associated risk factors, current screening recommendations, and preventive strategies. Emphasis is placed on clinical management and patient education regarding sun safety and the importance of early detection of skin cancer.

Course preview

Skin Cancer: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention

This module provides an overview of skin cancer, focusing on the most common types, associated risk factors, current screening recommendations, and preventive strategies. Emphasis is placed on clinical management and patient education regarding sun safety and the importance of early detection of skin cancer.

Upon completion of this module, learners should be able to:

- describe the epidemiology of skin cancer in the United States and identify the three most common types, highlighting their distinguishing clinical and pathologic characteristics

- apply the clinical ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter, and Evolution) to differentiate malignant lesions from benign nevi and review current evidence-based guidelines for skin cancer screening

- explain the role of ultraviolet (UV) radiation in skin carcinogenesis and identify key risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing skin cancer

- summarize the diagnostic process and treatment options for SCC, BCC, and melanoma and review melanoma staging criteria

- discuss best practices for skin cancer prevention across the lifespan

Skin cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, with cases continuing to rise each year due to a combination of environmental exposure and aging populations. Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), which include basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), represent over 98% of all cases of skin cancer. Although common, they are less aggressive than melanoma and are highly treatable when identified in the early stages. Melanoma is the most serious and potentially fatal skin cancer. Despite the risks associated with melanoma and the high incidence of BCC and SCC, skin cancer remains largely preventable. The majority of cases are linked to prolonged or intense exposure to UV radiation from sunlight or artificial sources such as tanning beds. As a result, public health initiatives have increasingly focused on prevention strategies, including sun safety education, skin protection behaviors, and community screening efforts. Health care professionals (HCPs)—including nurses—play a vital role in recognizing suspicious skin changes, guiding patients on sun safety, and promoting routine skin assessments. Since early-stage skin cancers are often curable with minimal intervention, all members of the health care team must remain vigilant (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2025a; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024, 2025; US Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 2023).

Epidemiology

Approximately 9,500 people in the United States are diagnosed with skin cancer each day. The incidence of skin cancer is higher than all other cancers combined, and incidence rates continue to rise, particularly in children and adolescents (Skin Cancer Foundation, 2024).

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

NMSCs are not typically reported to most cancer registries, making it challenging to accurately assess their incidence. However, research studies estimate that approximately 5.4 million new NMSC cases are diagnosed in the United States annually, and roughly 8 out of 10 are BCC. Treatment of NMSC increased by nearly 77% between 1994 and 2014, with an annual cost of $4.8 billion. It is estimated that approximately 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer throughout their lifetime and that 40%–50% of Americans who live up to age 65 will develop NMSC at least once. The increased incidence of skin cancer may be attributed to improved detection, increased sun exposure, and longer life expectancy (ACS, 2023b, 2025a, 2025b; CDC, 2024; Lim & Asgari, 2025; Wu, 2025).

BCC is the most common skin cancer, accounting for approximately 80% of NMSC cases, whereas SCC comprises the remaining 20%. Both BCC and SCC have higher incidence rates in areas with closer proximity to the equator. Epidemiologic studies have shown that higher UV radiation exposure at lower latitudes, such as in Hawaii, compared to higher latitudes, such as in the Midwest, is associated with an increased incidence of BCC. Despite the high incidence of NMSC, almost all cases of BCC and SCC can be cured, especially if detected early and treated adequately. Although the incidence is high, associated mortality is not. According to the ACS (2023b), deaths from NMSCs are estimated to range between 2,000 and 8,000 people annually, and mostly from SCCs. Most NMSC deaths are among the older adult population or those who did not seek treatment until the cancer was advanced (ACS, 2023b; Lim & Asgari, 2025; Wu, 2025).

Melanoma

Melanoma is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States, accounting for about 5% of all new cancer cases. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database--a government-funded program that compiles information on cancer statistics among the US population--it is estimated that in 2025, there will be approximately 104,960 new cases of melanoma diagnosed and about 8,430 related deaths. While melanoma accounts for a relatively small proportion of overall cancer deaths (around 1.4%), its incidence has been increasing steadily over the past several decades, especially among individuals with lighter skin tones and higher UV exposure. The overall age-adjusted incidence rate is about 23.8 per 100,000 people per year, and rates are significantly higher in those assigned male at birth. In fact, males have nearly double the incidence rate compared to those assigned female at birth, and the mortality rate for males is also higher, with 2.9 deaths per 100,000 males annually compared to 1.3 per 100,000 females (ACS, 2025a, 2025b; CDC, 2025; Curiel-Lewandrowski, 2025; National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2025).

Melanoma is strongly age-related, and most diagnoses occur in individuals aged 65 and older. The median age at diagnosis is 66, and the median age at death is 72. However, it remains one of the most common cancers in young adults, particularly among females under 30. When detected early, melanoma has a favorable prognosis, with a five-year relative survival rate of approximately 94.8% for localized disease. The survival rate decreases to 70.6% when the cancer has spread to regional lymph nodes and drops significantly to 32.1% for distant-stage (metastatic) disease. Racial disparities in melanoma outcomes are notable. While the vast majority of melanoma cases (about 94%) occur in non-Hispanic White individuals, people of color are often diagnosed at later stages, contributing to worse outcomes. For example, Black individuals have lower survival rates largely due to delayed detection and differences in tumor biology and access to care. Geographically, the highest melanoma incidence rates are seen in states with strong sun exposure and larger populations of light-skinned individuals. Regular skin examinations and public awareness about warning signs such as asymmetry, irregular borders, and color variation in visible skin lesions are critical for early detection. As melanoma rates continue to rise, particularly among older adults and males, these statistics underscore the importance of timely diagnosis and equitable access to dermatologic care (Curiel-Lewandrowski, 2025; NCI, 2025).

Anatomy and Physiology

The skin is the largest organ in the human body, protecting against sunlight, injury, heat, and infection....

...purchase below to continue the course

Epidermis

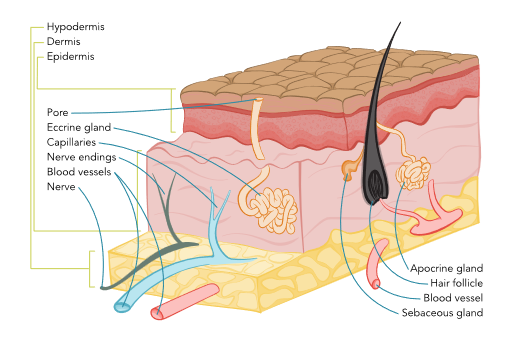

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin, protecting against microorganisms by providing a barrier against intruders from the outside environment (refer to Figure 1). The epidermis is divided into five layers, as outlined in Table 1, and is primarily composed of flat, keratinized, scale-like, stratified squamous epithelial cells. Keratinocytes are responsible for synthesizing the protein keratin, which forms a protective barrier for the body. Underlying this layer of skin are spherical-shaped basal cells, followed by the lowest inner level of the epidermis, which contains melanocyte cells. Melanocyte cells produce melanin, a protein pigment responsible for giving skin its natural color. Melanin also protects the skin from the harmful effects of UV radiation damage. The more melanin present, the darker the skin color. With sun exposure, melanocytes produce melanin, causing the skin to darken or tan. Clusters of melanocytes and surrounding tissue frequently create moles or nevi. Merkel cells are specialized cells located immediately below the epidermis and function as mechanoreceptors, responding to physical stimuli such as touch and pressure. Langerhans cells, located in the stratum spinosum, are the first line of defense against pathogens, triggering the immune response to foreign invaders (Agarwal & Krishnamurthy, 2023; Ignatavicius et al., 2023).

Figure 1

Skin Anatomy

Table 1

Layers of Epidermis (In order from most superficial to deepest)

Epidermal Layer | Composition | Function |

Stratum Corneum |

|

|

Stratum Lucidum |

|

|

Stratum Granulosum |

|

|

Stratum Spinosum |

|

|

Stratum Basale |

|

|

(Agarwal & Krishnamurthy, 2023; Ignatavicius et al., 2023)

Dermis

The dermis is the layer beneath the epidermis and comprises collagen-producing fibroblasts, which are responsible for giving the skin its strength, durability, and flexibility. The dermis contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, glands, hair follicles, and nerve endings. Blood vessels nourish the skin with oxygen and nutrients, deliver immune system cells to the skin to fight infection, and carry away waste products. Some of the glands produce sweat, which helps regulate body temperature, whereas others produce sebum, an oily substance that helps keep the skin from drying out. Nerves communicate signals from the skin, including touch, pain, pressure, temperature, and itching (Agarwal & Krishnamurthy, 2023; Ignatavicius et al., 2023).

Hypodermis

The deepest layer of the skin is the hypodermis, also known as the subcutaneous layer. Similarly to the dermis, it contains blood vessels and nerves but consists primarily of adipose tissue (a layer of fat). Adipose tissue cushions and protects against physical trauma or impact on internal organs, muscles, and bones and also helps regulate body temperature (Agarwal & Krishnamurthy, 2023; Ignatavicius et al., 2023).

Basics of Cancer Biology

Cancer arises from disruptions in the body’s natural cellular processes. Cells are the building blocks that make up all tissues within the human body, and these tissues, in turn, make up organs. Under normal circumstances, cells undergo a tightly regulated cycle of growth, division, and death. This cycle ensures that aging or damaged cells are replaced with new ones in an orderly and balanced manner. However, when these regulatory mechanisms break down, the result is uncontrolled cellular proliferation, which can lead to the formation of tumors. In the case of skin cancer, this deregulation occurs in the epidermal or dermal layers, often induced or exacerbated by environmental factors such as UV radiation. New cells may form unnecessarily, while old or damaged cells fail to die off as intended. These cells accumulate, behave abnormally, and may eventually develop into malignant cells (Ignatavicius et al., 2023).

Risk Factors

Actinic keratosis (AK) is a primary contributor to NMSCs. AK is a precancerous skin lesion caused by chronic sun exposure. Affecting more than 58 million Americans, AK is typically found on sun-exposed areas such as the face, ears, scalp, forearms, and hands, particularly in individuals with fair skin and those over the age of 40. These lesions appear as pink or flesh-toned scaly patches and are often rough in texture. Notably, around 65% of SCCs and 36% of BCCs originate from sites previously diagnosed with AK (ACS, 2024; Lim & Asgari, 2024, 2025; McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

Approximately 90% of NMSCs are associated with prolonged exposure to UV radiation. Common risk factors associated with UV exposure include fair skin, light eyes, and blonde or red hair, all of which contribute to reduced melanin production. Additional environmental and behavioral factors intensify the risk, such as residing near the equator, a history of blistering sunburns—especially during childhood or adolescence—and frequent use of tanning beds. A weakened immune system, including HIV infection or posttransplant immunosuppression, further elevates risk. Genetic conditions such as xeroderma pigmentosum and nevoid BCC syndrome are rare but potent risk factors, as these individuals have a higher susceptibility to DNA damage from UV exposure. In addition, certain localized factors also contribute to increased NMSC risk, such as chronic inflammatory skin conditions, prior scars or burns, and long-term exposure to toxic substances like arsenic, which can create an environment conducive to malignancy. Gorlin syndrome, a genetic condition resulting from a mutation of the PTCH1 gene, predisposes individuals to multiple BCCs at an early age (ACS, 2024, 2025a; Sathe & Zito, 2025; Lim & Asgari, 2025).

The risk of skin cancer is cumulative, meaning the total amount of sun exposure over one’s lifetime plays a significant role in disease development. UV rays can damage unprotected skin within just 15 minutes of exposure, although the visible effects—such as sunburn—may not appear for up to 12 hours later. Tanning is harmful; while it may not cause an immediate sunburn, it represents the skin’s defensive response to DNA damage. Over time, such damage accumulates, increasing the risk of premature aging, actinic damage, and various types of skin cancer (Lim & Asgari, 2025; McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Sathe & Zito, 2025).

Melanoma

Melanoma, the most aggressive and potentially lethal form of skin cancer, presents a distinct set of risk factors. Among the most significant include a personal or family history of melanoma. Having a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, child) with melanoma increases one’s risk, with a family history present in about 10% of all cases. Inherited genetic mutations and shared environmental exposures within families may both play a role. Dysplastic nevi, also known as atypical moles, are another significant risk factor. These moles differ from common nevi in color, size, and border definition. They can display several colors, from pink to dark brown, and are often larger than 6mm—typically wider than a pea and longer than a peanut—and exhibit irregular pigmentation or asymmetry. Dysplastic nevi are more likely than ordinary moles to undergo malignant transformation. Individuals with more than 50 moles, especially if some are atypical, are at higher risk of developing melanoma. While not all atypical moles develop into cancer, they serve as markers for an elevated risk of melanoma (Curiel-Lewandrowski, 2025; Heistein et al., 2024; NCI, 2022).

Exposure to artificial UV sources significantly increases the risk of melanoma. Indoor tanning beds are classified as carcinogenic by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. The use of tanning beds before the age of 35 increases the risk of melanoma by 75%. Moreover, even a single blistering sunburn during childhood can double the lifetime risk of melanoma. Five or more such burns before age 20 are associated with an 80% increased risk (ACS, 2025a; Curiel-Lewandrowski, 2025; Heistein et al., 2024; NCI, 2022; Skin Cancer Foundation, 2025).

UV Radiation

UV radiation is a form of electromagnetic energy emitted by the sun and certain artificial sources, such as sun lamps and tanning beds. Although it cannot be seen with the human eye, its biologic effects are profound. UV radiation is divided into three primary categories: UVA, UVB, and UVC. Of these, UVA and UVB rays penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere and have well-documented roles in skin damage and carcinogenesis. UVA rays are longer in wavelength and penetrate deeper into the skin, contributing to photoaging and immune suppression. UVB rays, although shorter in wavelength, are more biologically active and primarily responsible for sunburn. Both types of rays can damage cellular DNA in the skin. This damage, when left unrepaired or improperly repaired, can result in genetic mutations that lead to cancer. UV radiation does not need to cause a visible burn to be harmful; subclinical DNA changes may still occur, and these accumulate over time with repeated exposure (Curiel-Lewandrowski, 2025; Sathe & Zito, 2025; Wu, 2025).

The skin’s natural defense against UV radiation involves the production of melanin. Individuals with higher melanin levels—typically those with darker skin tones—are less likely to burn and have a lower relative risk of skin cancer. However, no skin type is immune to UV-induced damage, and protective behaviors are essential for all populations. Sunscreen with broad-spectrum (UVA and UVB) protection, protective clothing, and behavioral modifications such as seeking shade and avoiding tanning beds are crucial preventative measures (Sathe & Zito, 2025; Wu, 2025). Table 2 outlines the differences between these two types of rays.

Table 2

UVA Versus UVB Radiation Rays

UVA Radiation | UVB Radiation |

It has a longer wavelength and is associated with skin aging. | It has a shorter wavelength and is associated with skin burning. |

It damages the collagen and elastin in the skin, generates free radicals, and causes almost all forms of skin aging, including wrinkles (photoaging). | It plays a key role in the development of skin cancer by damaging cells and causing DNA mutations; it can eventually lead to melanoma and cataracts. |

It can penetrate deep into the skin’s dermis, resulting in a tan, and can penetrate through glass. | It does not penetrate as deeply as UVA, but it is the primary source of sunburn. It usually burns the superficial layers of the skin. |

It accounts for 95% of all the UV rays that reach the Earth’s surface. | It makes up only 5% of the UV rays from the sun, but it is very high energy. |

UVA is the primary radiation source emitted from tanning beds; UV rays produced by tanning units are 10 to 15 times more potent than UV rays produced by the midday sun. | The intensity of UVB rays varies by season, geographic location, and time of day, with the hours from 10 AM to 4 PM considered the peak period. |

(Saric-Bosanac et al., 2019)

UV radiation can penetrate light clothing, windows, and windshields. It is also reflected by sand, water, snow, and concrete. It can reach swimmers at least 1 foot below the water’s surface. Roughly 60% to 80% of the sun’s rays transmit through clouds, so clouds and water do not offer protection (Saric-Bosanac et al., 2019).

Screening and Early Detection

Early identification of skin cancer is crucial for improving outcomes. Nurses play a vital role in educating patients and assisting with appropriate evaluation and referrals when suspicious lesions are identified. The best way to detect skin cancer early is to be aware of new or changing skin growths, particularly those that look unusual. The ACS (2025a) recommends that an HCP promptly evaluate any new lesion or a progressive change in a lesion’s appearance (size, shape, or color change). Although some clinicians support total body skin examinations (TBSEs) as a cost-effective and low-risk strategy for early detection, there remains a lack of consensus on their routine use in the general population (Geller & Swetter, 2024). The USPSTF (2023) has issued an “I” statement, indicating that current evidence is insufficient to determine whether visual skin examinations by clinicians effectively reduce skin cancer–related morbidity or mortality in asymptomatic individuals without a personal history of skin cancer. The USPSTF recommendation applies specifically to adults and adolescents who are not experiencing skin-related symptoms and who have no previous history of precancerous or cancerous lesions. Therefore, TBSEs are not routinely included in annual physical exams by nondermatology providers. This neutral stance should not be confused with discouragement of skin exams. Instead, it reflects the need for more rigorous research, particularly randomized controlled trials, to assess the long-term benefit of visual screening in reducing deaths from skin cancer. Importantly, the USPSTF recommendation does not extend to higher-risk groups, including individuals with a prior skin cancer diagnosis. In such cases, clinical judgment remains paramount (USPSTF, 2023).

Patient Skin Self-examination

Although the USPSTF (2023) does not endorse self-examinations as a preventative measure due to insufficient evidence, several authoritative organizations—including the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), the ACS, and the Melanoma Research Alliance—advocate for monthly skin self-exam as a practice strategy for early detection. Self-examinations allow individuals to become familiar with the appearance of their skin and identify changes early (AAD, 2023; ACS, 2023a; Melanoma Research Alliance, n.d.). The AAD (2023) recommends monthly checks in a well-lit room, using both a full-length mirror and a handheld mirror. Tools such as body mapping diagrams or mobile apps can be helpful in tracking moles and identifying new or changing lesions. Patients are encouraged to bring their skin maps or digital images to clinical appointments (AAD, 2023). Resources such as the AAD’s “SPOT Skin Cancer” campaign offer free tools, including body maps and educational guides, to help patients learn and maintain this important self-care practice (AAD, 2022). To perform a thorough self-examination, patients should be taught to (AAD, 2022, 2023):

- Examine the entire body (front and back) in a full-length mirror.

- Inspect underarms, forearms, and palms.

- Check the legs, between the toes, and the soles of the feet.

- Use a hand mirror to examine the scalp, neck, and back.

- Examine the buttocks and genital area using mirrors as needed.

Recognizing Warning Signs

Skin cancer often begins subtly, making it essential for both HCPs and patients to recognize the early signs. Key indicators include:

- a mole or lesion that changes in size, shape, or color

- the development of a new growth on the skin

- a sore or ulceration that does not heal within a month

These symptoms should prompt timely clinical evaluation. Nurses should assess not only the lesion’s appearance but also inquire about any itching, bleeding, or tenderness associated with the area, as these may be signs of malignancy (Lim & Asgari, 2024; Swetter & Geller, 2023; Wu, 2025). The clinical presentation and key warning signs of the most common skin cancer will be reviewed in this section.

Actinic Keratosis

AK most commonly appears on chronically sun-exposed areas such as the face, scalp, ears, forearms, and hands. Clinically, they appear as dry, rough, scaly patches or spots, often in clusters. The texture is more prominent than the visual appearance. Patients frequently describe them as feeling like sandpaper. While actinic keratoses are not invasive cancers, they have the potential to progress to SCC if left untreated. The exact progression varies, but this risk underscores the importance of early recognition and of ensuring appropriate referral for dermatologic evaluation (Lim & Asgari, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Basal Cell Carcinoma

BCCs originate from basal cells in the lower layer of the epidermis. BCC lesions are slow-growing and rarely fatal, as they uncommonly spread to other parts of the body. However, these lesions can be highly disfiguring if allowed to grow and can cause extensive invasion into surrounding tissues. BCC can infiltrate nerves and bones, causing damage and disfigurement. BCC lesions often develop on regions of the body that receive regular sun exposure, such as the face and hands, but can form anywhere on the body, including the chest, abdomen, and legs. They appear as flesh-colored, pearly bumps or a raised pink or red translucent, shiny region. On darker-toned skin, BCCs can present with colors ranging from tan to black or brown and can easily be mistaken for a normal mole. Alternatively, they may present as an open sore, scar, or growth with rolled edges or a central indentation. These lesions may develop tiny surface blood vessels over time. Lesions may crust, ooze, itch, and often bleed following minor injury. To avoid misdiagnosing a lesion, HCPs must understand that BCC lesions may appear quite differently from one individual to another (McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025). The five most common warning signs of BCC include:

- a sore that does not heal or heals then reopens

- a red, irritated patch that may itch or crust

- a shiny bump or nodule, often pink or pearly

- a small pink growth with a raised border and central indentation

- a scar-like area that is white, yellow, or waxy, often with poorly defined borders (McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025)

BCCs are further classified into several subtypes based on clinical and histologic characteristics. Understanding these patterns supports accurate assessment and referral. Refer to Table 3 for an overview of these subtypes and their corresponding clinical features. Each subtype presents unique management challenges, with morpheaform BCC being notably more aggressive and difficult to treat due to its indistinct borders and deeper tissue involvement (McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Table 3

Common BCC Subtypes

Subtype | Key Characteristics |

Nodular BCC (refer to Figure 2) |

|

Pigmented BCC |

|

Morpheaform (Sclerotic) BCC |

|

Superficial BCC (refer to Figure 3) |

|

(McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025)

Figure 2

Nodular Basal Cell Carcinoma

(NCI, 2012a)

Figure 3

Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma

(NCI, 2012b)

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

SCCs arise from the keratinocytes in the epidermis. Although SCC is less common than BCC, it carries a higher risk of metastasis (spreading), particularly when it arises in high-risk locations, such as the lips or ears, or immunocompromised individuals. SCC lesions vary in appearance and may present as thick, crusted nodules (refer to Figure 4a), scaly plaques, or ulcerated growths. They are often red (refer to Figure 4b) or skin-colored and may bleed or become tender. The edges of the lesion may be raised, and blood vessels may be visible along the periphery. SCC is most frequently observed on sun-exposed sites, such as the face, scalp, neck, and hands. Since SCC has a higher potential to spread than BCC, early diagnosis and treatment are especially critical. Lesions that are left untreated can invade deeper tissues, including muscle and bone (Hadian et al., 2024; Lim & Asgari, 2024).

Figure 4

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Lesion, (a) Face and (b) Leg

(NCI, 2012c)

(NCI, 2012d)

Bowen’s disease, also known as SCC in situ, is considered an early, noninvasive form of SCC. It is confined to the epidermis and has not penetrated the dermis. Bowen’s disease is associated with chronic sun exposure and has been linked to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Clinically, Bowen’s disease presents as a slowly enlarging, scaly, red-brown patch of plaque with irregular but well-demarcated borders. These lesions are most often found on the lower extremities, particularly the legs, and occur more frequently in women. Although confined to the superficial skin layers, Bowen’s disease has the potential to progress to invasive SCC if left untreated (Hadian et al., 2024; Lim & Asgari, 2024).

Melanoma

Melanoma arises from the melanocyte cells and is characterized by radial and vertical growth. While most melanoma is referred to as cutaneous melanoma, which appears in the skin, it may also occur in the eye, and this condition is known as ocular melanoma. There are rare instances where melanoma arises in other areas, such as the lymph nodes or digestive tract. While melanoma can appear anywhere on the body, there are patterns in its anatomic distribution. In men, lesions tend to occur more commonly on the trunk, head, or neck. In women, the lower legs and feet are more frequently involved. Individuals with fair skin, a history of sunburns, or a family history of melanoma are at higher risk (Lim & Asgari, 2024; Wu, 2025).

One of the most widely used strategies for identifying suspicious pigmented lesions is the ABCDE rule, which serves as a practical tool for clinicians and patients. This mnemonic provides a systematic approach to evaluating moles and other skin changes that may indicate melanoma. Table 4 provides an overview of the clinical application of the ABCDE rule, comparing melanoma lesions with normal moles or benign nevi. While not all melanomas present with these features or meet the five criteria listed here, the ABCDE rule remains an essential clinical guide for triaging lesions that require biopsy or warrant referral to dermatology (Lim & Asgari, 2024; Swetter & Geller, 2023; Wu, 2025).

Table 4

ABCDE Rule of Melanoma

Letter | Characteristic | Description |

A | Asymmetry | One half of the lesion does not mirror the other. A benign mole is usually symmetrical; asymmetry can be a warning sign of malignancy. Refer to Figure 5. |

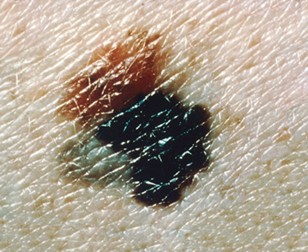

B | Border | Melanoma often has uneven, notched, or poorly defined edges, whereas benign lesions typically have smooth, regular borders. Refer to Figure 6. |

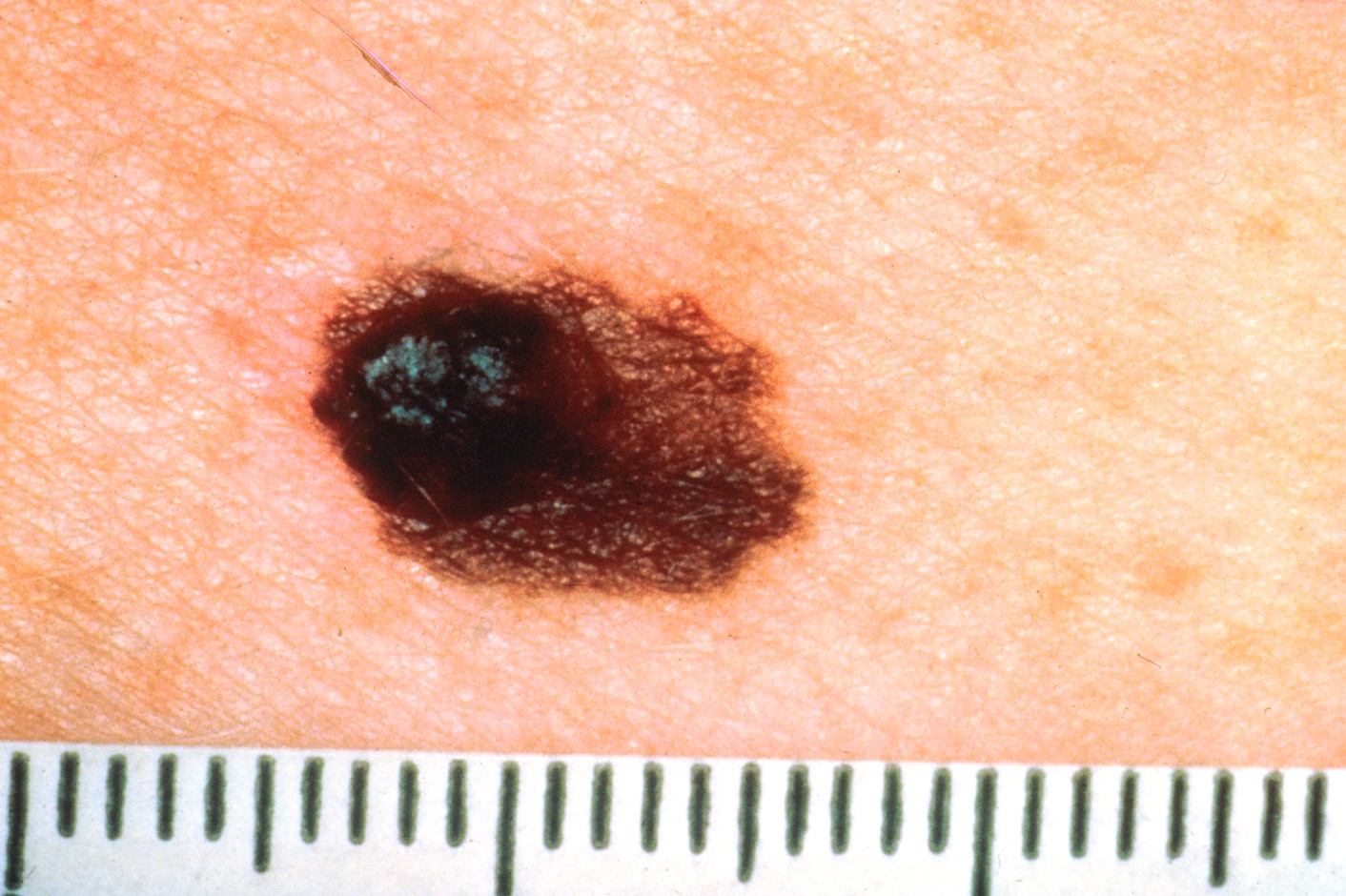

C | Color | Normal moles are uniform in color. Lesions that exhibit multiple colors, such as brown, black, tan, or white, should raise concern. Refer to Figure 7. |

D | Diameter | Melanomas are often larger than 6 mm (about the size of a pencil eraser), although early melanomas can be smaller. Refer to Figure 8. |

E | Evolution | Any change over time in the size, shape, color, or elevation of a mole or the development of new symptoms, such as bleeding or itching, is suspicious and warrants evaluation. |

(Lim & Asgari, 2024; Swetter & Geller, 2023; Wu, 2025)

Figure 5

Asymmetrical Melanoma Lesion

(NCI, 2001a)

Figure 6

Melanoma Lesion with Irregular, Notched Borders

(NCI, 2011a)

Figure 7

Melanoma Lesion with Variable Colors

(NCI, 2011b)

Figure 8

Melanoma Lesion with Large/Changing Diameter

(NCI, 2001b)

Melanoma is a heterogeneous disease with multiple histologic and clinical subtypes. Understanding these variations helps guide diagnosis and treatment decisions. The four primary types of cutaneous melanoma are superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, and acral-lentiginous melanoma.

Superficial Spreading Melanoma. This is the most prevalent subtype, accounting for approximately 70% of all melanomas. It typically grows horizontally along the top layer of the skin before penetrating deeper. Superficial spreading melanoma frequently arises from a preexisting mole and is commonly found on the back in both men and women, as well as on the legs in women. These lesions are often multicolored, with hues including tan, black, pink, and gray, and have irregular borders with a scaly or crusted surface.

Nodular Melanoma. This aggressive subtype accounts for 15–20% of melanomas and is characterized by rapid vertical growth. It appears as a dome-shaped, elevated lesion, often bluish-black, although it can lack pigment in some individuals. Nodular melanoma typically develops on the trunk, head, or neck and is more likely to be diagnosed at a later, more advanced stage due to its fast-growing nature.

Lentigo Maligna Melanoma. This subtype originates from a precursor lesion known as lentigo maligna, characterized by a large, flat, sun-damaged patch. It is most commonly found on chronically sun-exposed areas such as the face, neck, or hands. It is particularly common in older adults. These lesions tend to be tan to dark brown and have uneven borders. Over time, they may evolve into raised nodules as they progress to invasive melanoma.

Acral-Lentiginous Melanoma. Although rare, this subtype is the most common type of melanoma in individuals with darker skin tones. It often develops under the fingernails, toenails, and on the palms and soles. It appears as an irregular, flat, or slightly raised multicolored lesion with shades of tan, blue, and black. It can sometimes be mistaken for benign conditions such as warts or bruises, which may delay early diagnosis.

Table 5 outlines a brief comparison of the most common sites and features of each subtype (Heistein et al., 2024; Swetter & Geller, 2023).

Table 5

Melanoma Subtypes

Subtype | Common Sites | Key Features |

Superficial Spreading | Back (all genders), legs (females) | Irregular, multicolored plaque, often developing from preexisting nevus |

Nodular | Trunk, head, neck | Raised, dome-shaped, dark lesion with rapid vertical growth |

Lentigo Maligna | Face, neck, hands | Flat, freckle-like patch on sun-damaged skin |

Acral-Lentiginous | Palms, soles, nail beds | Dark, irregular lesions on acral surfaces, more common in darker skin tones |

(Heistein et al., 2024; Swetter & Geller, 2023)

Melanoma is less common in individuals with darker skin; however, when it does occur, it is more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage and in less visible areas. In these populations, melanoma often develops in non–sun-exposed sites such as the nail beds, soles of the feet, and palms. HCPs should be aware of these anatomic patterns and ensure comprehensive skin assessments are inclusive and culturally competent (Swetter & Geller, 2023). If not detected and treated early, melanoma can metastasize. The most common sites of distant spread include the lungs, liver, brain, bones, and gastrointestinal tract. Once metastatic, melanoma becomes significantly more difficult to treat and is associated with a lower survival rate (Heistein et al., 2024).

Diagnosis

Timely and accurate diagnosis of skin cancer plays a pivotal role in reducing patient morbidity and mortality. While many cases of NMSC are curable with complete surgical excision, early detection is especially critical in melanoma, where delayed treatment significantly increases the risk of metastasis and poor outcomes. The diagnostic process begins with a detailed patient history and comprehensive skin examination. A thorough history should include questions about cumulative sun exposure, history of sunburns (especially in childhood), tanning bed use, personal or family history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, and occupational exposures. Patients with fair skin, freckles, or a tendency to burn rather than tan are at higher risk for developing skin malignancies (Lim & Asgari, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Visual inspection of skin lesions remains the first step in clinical assessment. However, the accuracy of detecting malignancy is enhanced when clinicians conduct exams in a well-lit room and utilize adjunctive tools such as a dermatoscope. Dermoscopy (also known as dermatoscopy) is a noninvasive technique that enables enhanced visualization of subepidermal structures not visible to the naked eye. Dermatoscopy incorporates magnification and light, and applying a transparent medium (such as mineral oil, liquid paraffin, or ultrasound gel) to the skin improves clarity by reducing surface reflection. Dermoscopy improves diagnostic accuracy, particularly in distinguishing benign nevi from melanoma or identifying vascular patterns suggestive of basal or SCCs. This tool has become increasingly common in primary care and dermatology settings as part of the standard skin cancer workup (Sonthalia et al., 2023).

The Role of Biopsy

Although clinical tools and visual cues provide valuable information, histopathologic examination of a tissue sample remains the gold standard for confirming a diagnosis of skin cancer. Once a lesion is suspected of being malignant, a biopsy is necessary. The type of biopsy performed depends on the clinical characteristics, location, size of the lesion, and the suspected cancer subtype (Lim & Asgari, 2024; McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Punch Biopsy

A punch biopsy is ideal for small lesions (i.e., from 2 mm to 10 mm in diameter) and is a straightforward procedure performed in an office setting. The site is prepared with isopropyl alcohol, povidone-iodine, or chlorhexidine and anesthetized using 1% to 2% lidocaine. A disposable circular blade is often used, and the specimen is taken down to the level of the subcutaneous tissue. Larger punch biopsies (those measuring 8mm to 10mm) may require one or two sutures for wound closure and optimal cosmetic outcome. After the procedure, patients are advised to keep the area clean, avoid water for 24 hours, and apply a topical antibiotic such as bacitracin (Neosporin) twice daily (Lim & Asgari, 2024; McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Shave Biopsy

Shave biopsies are performed when the suspected lesion is confined to the superficial layers of the epidermis. A wheal of local anesthetic is injected to elevate the lesion, making it easier to excise with a scalpel or razor blade. This method is quick and straightforward, performed in the office setting, and typically does not require sutures. It is commonly used for lesions that are not deeply invasive, such as actinic keratoses or superficial BCC. However, shave biopsies should not be performed on pigmented lesions or any lesion where melanoma is suspected because they do not provide the full lesion depth required for melanoma staging. Following the procedure, standard wound care instructions should be provided, emphasizing the importance of keeping the wound clean through twice-daily application of bacitracin (Neosporin; Lim & Asgari, 2024; McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Excisional Biopsy

When melanoma is suspected, an excisional biopsy is the preferred method, as it provides the most complete information regarding tumor depth and margins. This procedure involves removing the entire lesion along with a narrow margin of healthy skin, typically 1 to 3 mm, and often extending into the subcutaneous fat. Excisional biopsies require a sterile environment and may be conducted in an outpatient surgical suite or clinic. The wound is closed with sutures, and patients receive detailed instructions for postprocedure wound care, including the use of antibiotic ointments and dressing changes (Lim & Asgari, 2024; McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025).

Special Considerations for Melanoma Biopsy

The depth of invasion, measured as Breslow thickness, is one of the most critical prognostic indicators in melanoma. Breslow thickness is the measurement of the depth of a melanoma. It is measured in millimeters from the skin’s surface to the deepest layer of the melanoma cells. If the lesion is ulcerated, then it is measured from the base of the ulcer to the deepest melanoma cell. Thicker melanoma lesions are associated with poorer survival outcomes. Therefore, a full-thickness biopsy is necessary when melanoma is suspected (North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, 2024). Partial biopsies can lead to inaccurate staging, which may delay appropriate treatment planning. In certain cases, an incisional biopsy (sampling a portion of the lesion) may be considered if it is too large or located in an area where complete excision could cause significant complications (Wu, 2025).

Nursing Considerations

Nurses play a crucial role in both the biopsy process and follow-up care. Patient education regarding postbiopsy wound management is vital for preventing infection and ensuring proper wound healing. Nurses should also be aware of contraindications to skin biopsies, such as a local infection at the biopsy site, which may delay the procedure until the infection is treated. Patients on anticoagulation therapy can typically undergo skin biopsy without discontinuing their medication, but bleeding risks should be assessed and minimized. Lesions on cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face, eyelids, or lips may require referral to a plastic surgeon or Mohs surgery for diagnostic accuracy and to ensure a favorable cosmetic outcome (Lim & Asgari, 2024; McDaniel & Steele, 2024; Wu, 2025).

NMSC Treatment

Management of NMSC varies depending on the type, size, depth, and location of the lesion. The primary goal is complete removal while minimizing recurrence and preserving healthy tissue. Most patients with localized NMSC are managed through surgical removal of the lesion. However, a range of both surgical and nonsurgical modalities are available, allowing for individualized treatment planning based on the patient’s needs, risk factors, and cosmetic considerations (Aasi, 2025; Hadian et al., 2024; McDaniel & Steele, 2024).

Surgical Excision

Surgical excision is the cornerstone of NMSC treatment, involving the removal of the cancerous lesion along with a margin of surrounding healthy tissue to ensure the complete removal of all cancerous cells. The specimen is sent for histologic analysis to confirm negative margins, meaning that no residual cancer cells exist at the edge of the excised tissue. Surgical excision has a high success rate, particularly for small, primary tumors that have not deeply invaded surrounding structures (McDaniel & Steele, 2024).

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery, also known as cryotherapy, utilizes extreme cold to destroy abnormal tissue and is commonly performed for actinic keratoses and superficial BCCs. During the procedure, the lesion is frozen (typically with liquid nitrogen) and then repeatedly thawed, resulting in cellular destruction. Since the effectiveness of cryosurgery depends on the lesion’s depth, it is not recommended for invasive or deeply infiltrative cancers. Cryosurgery is a quick, outpatient treatment but may result in hypopigmentation and scarring. It can also cause redness, swelling, pain, and blistering of the affected site (Aasi & Hong, 2025).

Curettage and Electrodesiccation

Curettage and electrodesiccation is a technique used for small, superficial BCCs and SCCs. The lesion is scraped with a curette, and then an electrical current is applied to the area to destroy any residual cancer cells. This method is most effective for nonaggressive lesions located in low-risk areas such as the trunk or extremities. It is not frequently used for lesions on the face or ears, where scarring may be more noticeable. Curettage and electrodesiccation can cause side effects, including swelling, pain, crusting, bleeding, and scarring at the affected site (Hadian et al., 2024; McDaniel & Steele, 2024).

Topical Therapies

For some superficial lesions, topical agents may be an appropriate treatment option, especially for patients who are poor surgical candidates or have multiple lesions. 5-fluorouracil (Efudex, Carac) is a commonly used chemotherapeutic agent effective against actinic keratoses, superficial BCC, and Bowen’s disease. It is applied as a cream and targets abnormal skin cells while sparing healthy tissue. Treatment duration can vary, but it typically involves using the cream for several weeks. Patients should be counseled on the expected side effects of redness, inflammation, and peeling (Aasi, 2025).

Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery is a more advanced and targeted surgical technique. It is considered the most precise and tissue-sparing surgical method for treating high-risk or recurrent NMSC. This procedure is particularly indicated for lesions in cosmetically or functionally important regions such as the nose, eyelids, lips, and ears. It is also used for tumors with poorly defined borders or aggressive histologic subtypes. Mohs surgery is performed in sequential stages during a single appointment. Initially, a thin layer of tissue containing the tumor is removed. The tissue is then examined under a microscope to identify whether cancerous cells remain. If residual cancer is detected, the surgeon maps and removes only the affected area, repeating the process until the margins are clear. This technique ensures the complete removal of cancer while preserving as much healthy tissue as possible. It also minimizes unnecessary removal of surrounding skin, reducing the risk of disfigurement and improving cosmetic outcomes (Aasi, 2025; McDaniel & Steele, 2024).

Once the skin cancer has been excised, the surgeon focuses on managing the wound to support proper healing. According to the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS), techniques used to manage wounds may include allowing the area to heal on its own without sutures, stitching the wound directly, or using a skin flap from nearby tissue or a skin graft from another part of the body to cover the surgical site. Most patients tolerate this outpatient procedure well and are able to drive themselves home. Potential risks include discomfort, bleeding, scarring, discoloration, and nerve damage. In rare cases, some patients may need additional reconstructive surgery. Patients who require stitches must return to the surgeon’s office within 1 to 3 weeks for suture removal (ASDS, 2025).

The cure rates associated with Mohs surgery are high, up to 99% for untreated skin cancer lesions and up to 94% for recurrent skin cancer after prior treatment. Due to the procedure’s complexity, Mohs surgery should be performed by a specially trained dermatologic surgeon and is typically limited to specialized surgical centers or dermatology practices equipped for on-site histologic processing (Aasi, 2025; McDaniel & Steele, 2024).

Recurrence Risk and Follow-Up

Even with complete removal, NMSCs can recur, especially if cancer cells extend beyond the visible edges of the lesion or are left behind due to microscopic spread. Certain sites are associated with a higher risk of recurrence. For example, BCCs on the ears, nose, and lips are more likely to recur within the first two years following treatment. Risk factors for recurrence include the following (Hadian et al., 2024):

- incomplete excision or positive surgical margins

- high-risk histologic features (e.g., morpheaform subtype)

- perineural invasion

- immunosuppressed status

- previous radiation therapy at the lesion site

Routine surveillance following treatment is necessary. The frequency and duration of follow-up visits depend on the risk of recurrence and the patient’s history. In general, patients should undergo a full skin examination every 6 to 12 months for at least two years after treatment, with particular attention to the original lesion site and sun-exposed areas (Aasi & Hong, 2025).

Melanoma Staging and Treatment

Once melanoma is confirmed through biopsy, accurate staging is essential to guide prognosis and treatment decisions. The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system is the most widely accepted tool for classifying melanoma. This system takes into account factors such as tumor thickness, ulceration status, lymph node involvement, and distant metastases. Correspondingly, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) provides evidence-based treatment guidelines that align with the stage of the disease, supporting clinical decision-making. Melanoma is categorized into five stages (0–IV), each reflecting the extent of tumor progression. Table 6 summarizes these stages along with general treatment considerations. Accurate staging is critical not only for treatment planning but also for determining eligibility for clinical trials and predicting outcomes. Treatment plans should be guided by NCCN recommendations and individualized based on patient-specific factors such as tumor biology, comorbidities, and overall performance status (NCCN, 2025; Pathak & Zito, 2023).

Table 6

The Five Stages of Melanoma

Stage | Description | General Treatment Approach |

Stage 0 (Melanoma in situ) |

|

|

Stage I (Localized) |

|

|

Stage II (Localized, Higher Risk) |

|

|

Stage III (Regional Spread) |

|

|

Stage IV (Distant Metastatic Disease) |

|

|

(Melanoma Research Alliance, n.d.; NCCN, 2025; Pathak & Zito, 2023)

Systemic Therapy for Advanced and Metastatic Melanoma

The treatment landscape for advanced and metastatic melanoma has evolved significantly over the last several years through the development of systemic therapies that target specific molecular pathways or activate the immune system. These therapies have significantly improved survival rates and are now the standard of care for patients with unresectable stage III or stage IV disease. The selection of systemic treatment is based on several factors, including BRAF mutation status, disease burden, central nervous system (CNS) involvement, and patient comorbidities (Seth et al., 2023).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are a cornerstone of systemic treatment for metastatic melanoma. They enhance the immune response against melanoma by blocking proteins that normally inhibit T-cell activation, thereby allowing the body to identify and target cancer cells more effectively. Anti-programmed death-1 (anti-PD-1) inhibitors are a type of ICI designed to help the immune system fight cancer more effectively. Normally, the immune system has built-in “brakes” to prevent it from attacking healthy cells. One of these brakes is a protein called PD-1, which is found in T-cells. When PD-1 connects with another protein called PD-L1, it sends a signal that tells the T-cell to slow down or stop its activity. Some cancer cells produce PD-L1 to trick the immune system. By binding to PD-1, they “turn off” the T-cells, which allows the cancer to grow unchecked. Anti-PD-1 drugs, such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo), block this connection between PD-1 and PD-L1. By doing so, they remove the brake and allow T-cells to remain active—enabling them to recognize and attack cancer cells. These drugs are typically used as first-line therapy for patients with advanced melanoma. They are generally well tolerated, and the most common side effects include fatigue, skin rash, arthralgia, cough, and fever. However, they carry a risk of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which can affect any organ system (e.g., lungs, colon, liver, thyroid) and may require corticosteroids or necessitate treatment cessation (Kreft et al., 2025; NCCN, 2025).

Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is a type of ICI that targets the protein cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), which is found on T-cells. CTLA-4 acts like a brake, keeping the immune system from becoming overactive. Ipilimumab (Yervoy) activates the immune system by blocking the CTLA-4 checkpoint. In the treatment of metastatic melanoma, ipilimumab (Yervoy) may be administered in combination with nivolumab (Opdivo). Side effects of ipilimumab (Yervoy) include fatigue, skin rash, arthralgia, and itching. While rare, some patients develop severe irAEs that can be fatal if untreated, including severe colitis with bowel perforation, liver failure, neurologic events, adrenal crisis, or pituitary dysfunction. Early recognition and intervention are key. Most irAEs are reversible if caught early and treated with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive therapy (Kreft et al., 2025; NCCN, 2025).

Approximately 50% of patients with melanoma have an activating BRAF V600 mutation, most commonly V600E. This mutation leads to the continuous activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, a key pathway that normally regulates cell growth and division. As a result, the mutation promotes uncontrolled tumor growth and survival. For these patients, targeted therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors offers a highly effective therapeutic strategy and alternative to immunotherapy. These drugs are usually used in combination to target both pathways simultaneously. US Food & Drug Administration (FDA)–approved BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations include the following (Priantti et al., 2023):

- dabrafenib (Tafinlar) + trametinib (Mekinist)

- vemurafenib (Zelboraf) + cobimetinib (Cotellic)

- encorafenib (Braftovi) + binimetinib (Mektovi)

These oral targeted therapies induce rapid tumor shrinkage and are especially useful in patients requiring immediate disease control. They are commonly used as first-line treatment or after progression on immunotherapy. Side effects include skin rash, photosensitivity, fatigue, arthralgias, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, blurred vision, anemia, and neutropenia. MEK inhibitors can cause cardiotoxicity, including decreased ejection fraction, QT prolongation, and heart failure. BRAF inhibitors carry a risk of secondary cutaneous malignancies such as SCC, but the incidence declines when they are combined with MEK inhibitors (NCCN, 2025; Priantti et al., 2023; Sosman, 2024).

Novel therapies for the treatment of metastatic melanoma include relatlimab (Opdualag) and talimogene laherparapvec (T-VEC). Relatlimab (Opdualag), a LAG-3 inhibitor, is approved in combination with nivolumab (Opdivo). LAG-3 is another checkpoint protein that inhibits T-cell activity. This combination has demonstrated promising results in extending progression-free survival in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Talimogene laherparapvec (T-VEC) is a genetically modified oncolytic viral therapy indicated for the local treatment of unresectable, recurrent melanoma. It utilizes a modified herpes simplex virus to kill melanoma cells and stimulate a systemic immune response (Ferrucci et al., 2021; Tawbi et al., 2024).

Skin Cancer Follow-up Care

Patients with NMSC or melanoma skin cancer who completed treatment still require follow-up surveillance at regular intervals. Follow-up is often recommended for patients with BCC every 6 to 12 months. For those with SCC, monitoring is usually more frequent than BCC, such as every 3 to 6 months for the first few years. If the patient remains without evidence of recurrent cancerous lesions, follow-up intervals can be extended. Surveillance for melanoma is more complicated. Surveillance depends on the stage of cancer at diagnosis, treatment response, residual disease following treatment, and the need for ongoing treatment. Melanoma in situ treated with wide local excision and negative margins is considered cured. According to the NCCN guidelines, patients with stages 0, I, and IIA should undergo complete skin examinations every 6 to 12 months for the first two years, followed by annual examinations thereafter. For patients with stage IIB-IV, the NCCN recommended follow-up every 3 to 6 months for the first two years, and every 6 to 12 months from years 3 to 5. In patients with a history of brain metastases and those at high risk for brain metastases (e.g., those with stage IIIC-IV), the NCCN advises more frequent brain imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). For all patients with a prior history of melanoma, the NCCN guidelines recommend at least annual skin exams for life (NCCN, 2025; Pathak & Zito, 2023).

Skin Cancer Prevention and Sun Safety

Ongoing public health efforts focus on prevention through sun protection and education, with a particular emphasis on targeting high-risk groups. Minimizing sun exposure is the key to preventing skin cancer. According to ACS researchers, most melanoma cases and deaths are potentially preventable by reducing exposure to intense and damaging UV radiation. The USPSTF (2023) recommends counseling all young adults, adolescents, children, and parents of young children about minimizing exposure to UV radiation for persons aged 6 months to 24 years with a fair skin type to reduce their risk of skin cancer (category B recommendation) and selectively offering counseling (based on risk factors) to adults older than 24 years with a fair skin type (category C recommendation). The following is a compilation of evidence-based interventions to educate patients on how to reduce the risk of skin cancer induced by UV radiation:

- avoid sunbathing or indoor tanning

- seek shade when outdoors; however, understand that while the shade is an effective mode of reducing UV radiation, it does not eliminate the exposure completely

- avoid exposures to midday sun when the sun’s UV rays are strongest and can do the most damage to the skin (from 10 AM through 4 PM)

- wear protective clothing made of tightly woven fabric (e.g., long sleeves, a wide-brimmed hat, and long pants.) when outside; a hat with a brim of at least 6 inches in circumference is recommended, as it protects the face, neck, and ears; baseball caps do not protect the back of the neck or the tops of the ears

- wear sunglasses with UV-absorbing lenses to block UV rays; seek sunglasses that protect the sides of the eyes and lenses that offer protection against both UVA and UVB rays; sun exposure increases the risk of cataracts

- apply a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 30 to unprotected skin every day, regardless of anticipated sun exposure and even on cloudy days

- adequate sun protection should be ensured while driving or sitting near windows due to exposure to UVA and UVB rays through the glass, especially to the hands, arms, neck, and face

- be mindful of medications, as some over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription medications can increase photosensitivity (sensitivity to harmful sun rays). A few of the most common ones include:

- antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl)

- ibuprofen (Motrin)

- certain antibiotics such as tetracyclines (doxycycline [Monodox] and minocycline [Minocin])

- certain antidepressant medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine [Prozac] or citalopram [Celexa])

- several types of chemotherapeutic agents, such as capecitabine (Xeloda), doxorubicin (Adriamycin), or fluorouracil (5-FU; Guerra et al., 2023; Young & Tewari, 2024)

HCPs should educate patients to use broad-spectrum sunscreen, which protects against UVA and UVB rays. Sunscreens are rated in strength according to SPF. The higher the SPF, the greater the sunburn protection it provides. Sunscreen should have an SPF of 30 or higher and be water-resistant. HCPs should caution patients that sunscreen does not offer 100% protection against the sun’s harmful UV rays, so the foregoing precautions must be taken to ensure safety. Additional patient teaching points include the following (Guerra et al., 2023; Young & Tewari, 2024):

- Use sunscreen every day, even on cloudy days. Up to 80% of the sun's harmful UV rays can penetrate the skin through clouds.

- Snow, sand, and water increase the need for sunscreen as they reflect the sun’s rays.

- Apply enough sunscreen to cover all exposed skin. Most adults need approximately 1 ounce to cover their entire body.

- Rub sunscreen in well to dry skin.

- Reapply at least every 2 hours when outside and more frequently after swimming, sweating, or toweling off.

- Ensure the sunscreen has not expired, as some ingredients in sunscreen break down over time.

- Sunscreen should be applied at least 15 minutes before exposure to all areas that the sun’s rays may reach. Pay special attention to areas commonly omitted when applying sunscreen, including the tips of the ears, the back of the neck, and bald spots on the top of the head.

- Apply protective lip treatment with an SPF of at least 15 to protect the lips from sun exposure.

- Type of sunscreen:

- Products that include zinc oxide offer the safest sun protection.

- Available sunscreen options include lotions, creams, gels, ointments, wax sticks, and sprays.

- Creams are best for dry skin and the face.

- Gels are ideal for hairy areas, such as the scalp or male chest.

- Sunscreen sticks are good to use around the eyes.

- Patients sometimes prefer sprays since they are easy to apply. However, current FDA regulations on testing and standardization do not pertain to spray sunscreens; many organizations advise against their use.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is essential for healthy bones, muscles, and teeth. The human body makes vitamin D when exposed to sunlight (specifically UVB, which is processed through the skin). While sunlight is essential for vitamin D production, patients must be counseled on the importance of being cautious about the amount of sun exposure they receive. Generally, the lighter one’s skin tone, the less sunlight is required to produce vitamin D. The body only needs about 15 minutes of unimpeded sun exposure, two to three times a week, to meet its vitamin D requirements. This small amount of sun exposure generates all the vitamin D the body requires. Beyond that, the body begins to eliminate vitamin D to prevent an overdose. At this point, sun exposure poses risks without any presumed benefits. In addition to sunlight, vitamin D can be obtained through a balanced diet. Diets that include egg yolks, oily fish (such as salmon, tuna, sardines, or eel), fortified milk, and cereal can help satisfy vitamin D needs without requiring sun exposure. Alternatively, patients can be advised to take vitamin D supplements (Guerra et al., 2023; Young & Tewari, 2024).

Special Considerations for Children and Adolescents

As described earlier, sunburns in childhood significantly increase the risk of melanoma later in life. Children with fair skin, red or blonde hair, freckles, and light-colored eyes are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of UV radiation. Avoiding sunlight and limiting exposure to it, along with implementing sun protection measures, can help reduce the risk of toxic overexposure. Parents should be taught to apply sunscreen generously with an SPF of at least 30 to their child’s body. They should cover exposed skin with approximately 1 ounce of sunscreen 15 to 20 minutes prior to going outside and reapply it every 2 hours, even on cloudy days, and after swimming or sweating. Infants younger than six months should never be exposed to direct sunlight and should be dressed in tightly woven, long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and brimmed hats that offer the best protection. Traditionally, it was advised to avoid applying sunblock to infants under six months old, but the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has published new guidelines supporting its use. Research has shown that the risk of sunburn is greater than that of chemical exposure. The AAP advises keeping infants under six months out of direct sunlight, recommending seeking shade under an umbrella, a tree, or a stroller canopy. When adequate clothing and shade are unavailable, parents are advised to apply sunscreen on small areas of the body, such as the face, if protective clothing and shade are not available. Clothing, especially swimsuits, can be manufactured with SPF fabric. Some small tents and umbrellas are designed with SPF 50 fabric to simultaneously protect the entire family when seated underneath it with no chemical exposure (AAP, 2024).

For nurses, understanding the pathogenesis of skin cancer and the interplay between UV radiation, genetic predisposition, and behavioral risk factors is essential for prevention, early detection, and patient education. Skin cancer is one of the most preventable malignancies, yet its incidence continues to rise. As frontline HCPs, nurses play a crucial role in identifying individuals at risk, promoting sun safety behaviors, and supporting early diagnosis through clinical vigilance. With increasing public awareness and evidence-based preventive strategies, many skin cancers can be avoided or successfully treated in their early stages.

Aasi, S. Z. (2025). Treatment and prognosis of basal cell carcinoma at low risk of recurrence. UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prognosis-of-basal-cell-carcinoma-at-low-risk-of-recurrence

Aasi, S. Z., & Hong, A. M. (2025). Treatment and prognosis of low-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC). UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prognosis-of-low-risk-cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma-cscc

Agarwal, S., & Krishnamurthy, K. (2023). Histology, skin. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537325

American Academy of Dermatology. (2022). Infographic: Skin cancer body mole map. https://www.aad.org/diseases/skin-cancer/body-mole-map

American Academy of Dermatology. (2023). Find skin cancer: How to perform a skin self-exam. https://www.aad.org/skin-cancer-find-check

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2024). Sun safety: Information for parents about sunburns & sunscreen. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/at-play/Pages/Sun-Safety.aspx

American Cancer Society. (2023a). Can basal and squamous cell skin cancers be found early? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/basal-and-squamous-cell-skin-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html

American Cancer Society. (2023b). Key statistics for basal and squamous cell skin cancers. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/basal-and-squamous-cell-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

American Cancer Society. (2024). What are basal and squamous cell skin cancers? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/basal-and-squamous-cell-skin-cancer/about/what-is-basal-and-squamous-cell.html

American Cancer Society. (2025a). Cancer facts & figures 2025. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2025-cancer-facts-figures.html

American Cancer Society. (2025b). Key statistics for melanoma skin cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. (2025). Mohs surgery for skin cancer. https://www.asds.net/skin-experts/skin-treatments/mohs-surgery

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Skin cancer basics. https://www.cdc.gov/skin-cancer/about/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Melanoma of the skin statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/skin-cancer/statistics/

Curiel-Lewandrowski, C. (2025). Risk factors for the development of melanoma. UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/risk-factors-for-the-development-of-melanoma

Ferrucci, P. F., Pala, L., Conforti, F., & Cocorocchio, E. (2021). Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC): An intralesional cancer immunotherapy for advanced melanoma. Cancers (Basel), 13(6), 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061383

Geller, A. C., & Swetter, S. (2024). Screening for melanoma in adults and adolescents. UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-melanoma-in-adults-and-adolescents

Guerra, K. C., Zafar, N., & Crane, J. S. (2023). Skin cancer prevention. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519527

Hadian, Y., Howell, J. Y., Ramsey, M. L., & Buckley, C. (2024). Cutaneous squamous cell skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441939

Heistein, J. B., Acharya, U., & Mukkamalla, S. K. R. (2024). Malignant melanoma. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470409

Ignatavicius, D. D., Rebar, C. R., & Heimgartner, N. M. (2023). Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts for clinical judgment and collaborative care (11th ed.). Elsevier.

Kreft, S., Bosetti, T., Lee, R., & Lorigan, P. (2025). Selecting first-line immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: Current evidence on efficacy across diverse populations. EJC Skin Cancer, 3(100285). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcskn.2025.100285

Lim, J. L., & Asgari, M. (2024). Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC): Clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma-cscc-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

Lim, J. L., & Asgari, M. (2025). Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Epidemiology and risk factors. UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma-epidemiology-and-risk-factors

Melanoma Research Alliance. (n.d.). Melanoma staging. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.curemelanoma.org/about-melanoma/melanoma-staging/

McDaniel, B., & Steele, R. B. (2024). Basal cell carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482439/

National Cancer Institute. (2001a). Asymmetrical melanoma [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=2362

National Cancer Institute. (2001b). Melanoma with diameter change [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=2365

National Cancer Institute. (2011a). Melanoma [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9188

National Cancer Institute. (2011b). Melanoma [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9189

National Cancer Institute. (2012a). Skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma, nodular [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9234

National Cancer Institute. (2012b). Skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma, superficial [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9236

National Cancer Institute. (2012c). Skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, face [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9248

National Cancer Institute. (2012d). Skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, leg [image]. https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9249

National Cancer Institute. (2022). Common moles, dysplastic nevi, and risk for melanoma. https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/moles-fact-sheet

National Cancer Institute. (2025). Cancer stat facts: Melanoma of the skin. National Institute of Health: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2025, January 28). NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Melanoma: Cutaneous, version 2.2025. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf

North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. (2024). Breslow tumor thickness. https://apps.naaccr.org/ssdi/input/melanoma_skin/breslow_thickness/

Pathak, S., & Zito, P. M. (2023). Clinical guidelines for the staging, diagnosis, and management of cutaneous malignant melanoma. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572149/

Priantti, J. N., Vilbert, M., Madeira, T., Moraes, F. C., Hein, E. C., Saeed, A., & Cavalcante, L. (2023). Efficacy and safety of rechallenge with BRAF/MEK inhibitors in advanced melanoma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 15(15), 3754. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153754

Saric-Bosanac, S. S., Clark, A. K., Nguyen, V., Pan, A., Chang, F., Li, C., & Sivamani, R. K. (2019). Quantification of ultraviolet (UV) radiation in the shade and in direct sunlight. Dermatology Online Journal, 25(7), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.5070/D3257044801

Sathe, N. C., & Zito, P. M. (2025). Skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441949

Seth, R., Agarwala, S. S., Messersmith, H., Alluri, K. C., Ascierto, P. A., Atkins, M. B., Bollin, K., Chacon, M., Davis, N., Faries, M. B., Funchain, P., Gold, J. S., Guild, S., Gyorki, D. E., Kaur, V., Khushalani, N. I., Kirkwood, J. M., Leigh, J., McQuade, J. L., . . . Weber, J. (2023). Systemic therapy for melanoma: ASCO guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 41(30), 4794–4823. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.01136

Skin Cancer Foundation. (2024). Skin cancer facts & statistics. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts/

Skin Cancer Foundation. (2025). Tanning & your skin. https://www.skincancer.org/risk-factors/tanning

Sonthalia, S., Yumeen, F., & Kaliyadan, F. (2023). Dermoscopy overview and extradiagnostic applications. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537131

Sosman, J. A. (2024). Overview of the management of advanced cutaneous melanoma. UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-management-of-advanced-cutaneous-melanoma

Swetter, S., & Geller, A. C. (2023). Melanoma: Clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/melanoma-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

Tawbi, H. A., Hodi, F. S., Lipson, E. J., Schadendorf, D., Ascierto, P. A., Matamala, L., Gutierrez, E. C., Rutkowski, P. P., Gogas, H., Lao, C. D., De Menezes, J. J., Dalle, S., Arance, A. M., Grob, J., Ratto, B., Rodriguez, S., Mazzei, A., Dolfi, S., & Long, G. V. (2024). Three-year overall survival with nivolumab plus relatlimab in advanced melanoma from RELATIVITY-047. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 43(13). https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.24.01124

US Preventive Services Task Force. (2023). Screening for skin cancer: US Preventative Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 329(15), 1290-1295. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.4342

Wu, P. A. (2025). Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical features of basal cell carcinoma. UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-pathogenesis-and-clinical-features-of-basal-cell-carcinoma

Young, A. R., & Tewari, A. (2024). Patient education: Sunburn prevention (beyond the basics). UpToDate. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sunburn-prevention-beyond-the-basics

Powered by Froala Editor