About this course:

This course explores venous thromboembolism (VTE), including the condition's definition and incidence in the United States. In addition, this course reviews the pathophysiology, various risk factors, and clinical manifestations of VTEs. Finally, this course reviews the process of diagnosis, various prevention and treatment modalities, and complications associated with VTE treatment.

Course preview

Venous Thromboembolism for Nurses

This course explores venous thromboembolism (VTE), including the condition's definition and incidence in the United States. In addition, this course reviews the pathophysiology, various risk factors, and clinical manifestations of VTEs. Finally, this course reviews the process of diagnosis, various prevention and treatment modalities, and complications associated with VTE treatment.

After this activity, learners will be prepared to:

- define types of VTE, such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

- describe the incidence and pathophysiology of VTEs.

- identify various risk factors and clinical manifestations of VTEs.

- discuss the process of diagnosing VTEs.

- describe the various prevention and treatment modalities for VTE, including complications associated with treatment.

Venous thromboembolism refers to blood clots that start in a vein and encompass two pathologies: deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). VTEs are caused by slow blood flow, damaged blood vessel lining, increased estrogen, or a change in the makeup of the blood that facilitates clotting. VTEs are the third leading vascular diagnosis after heart attacks and strokes, with approximately 10 million cases annually. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that the incidence of VTEs could be as high as 900,000 people each year, which equates to 1 to 2 cases per 1,000 people as many cases go undiagnosed. The associated health care costs are $10 billion or more annually in the United States. The CDC also estimates that 60,000 to 100,000 Americans die each year from a VTE, with 10% to 30% dying within a month of diagnosis. Sudden death occurs in approximately 25% of people who have a PE. Not only is there a high risk for mortality related to VTEs, but also an estimated one-third to one-half of patients diagnosed with a DVT will have long-term complications (i.e., post-thrombotic syndrome [PTS]), including pain, swelling, discoloration, and scaling in the affected limb. In addition, approximately 33% of people with a VTE will have a recurrence within 10 years of diagnosis. Although there are many risk factors for VTEs, about 5% to 8% of Americans have a genetic risk factor (i.e., inherited thrombophilia; American Heart Association [AHA], 2023c; CDC, 2024a, 2024b, 2024c; Gregson et al., 2019; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2022).

When a blood clot occurs due to surgery, hospitalization, or another health care treatment or procedure, it is known as health care–associated venous thromboembolism (HA-VTE). More than one-third of VTE cases are related to recent hospitalization, with 60% of them not occurring up to 90 days after discharge. HA-VTEs are the leading cause of preventable hospital death. They are the fifth most common reason for unplanned hospital readmissions after surgery and the third most common among patients undergoing knee and hip replacements. It is estimated that 70% of HA-VTEs are preventable through measures such as compression stockings and anticoagulation medications, but as few as 50% of patients receive the prevention measures. Overall, patients with HA-VTEs are three times more likely to be readmitted to the hospital than patients without HA-VTEs (CDC, 2024b, 2024c).

Pathophysiology

The body requires adequate perfusion to ensure oxygenation and nourishment of tissues, which depend on a properly functioning cardiovascular system. Adequate blood flow throughout the body depends on sufficient circulating blood volume and the efficiency of the heart to pump that blood through blood vessels. Patent, intact, and responsive blood vessels are necessary to deliver oxygen to the tissues and remove metabolic wastes. Arteries are thick-walled structures that carry blood from the heart to the tissues, while veins are less muscular, thin-walled structures that carry blood back to the heart. The walls of arteries and veins have three layers, including the intima, media, and adventitia. The thinner, less muscular walls of the veins allow the vessels to distend more than arteries and permit large volumes of blood to remain in the veins under low pressure (i.e., approximately 75% of the total blood volume remains in the veins). The sympathetic nervous system stimulates the veins to constrict, which reduces venous blood volume and increases the volume of blood circulating throughout the body. Within the extremities, skeletal muscle contraction creates a pumping action to facilitate blood flow back to the heart. Since the veins in the lower extremities must carry blood against the force of gravity, they are equipped with valves that prevent blood from seeping backward. Arteries can become obstructed or damaged due to atherosclerotic plaques, chemical or mechanical trauma, thromboembolism, vasospastic disorders, infections or inflammatory processes, and congenital malformations. Arterial occlusion can occur suddenly or gradually over time. A sudden occlusion can lead to profound and often irreversible tissue ischemia and death, while a gradual occlusion poses a lower risk of significant damage. When a gradual occlusion occurs, collateral circulation can develop, allowing the tissues to adapt to decreased blood flow (Chaudhry et al., 2022; Hinkle et al., 2021).

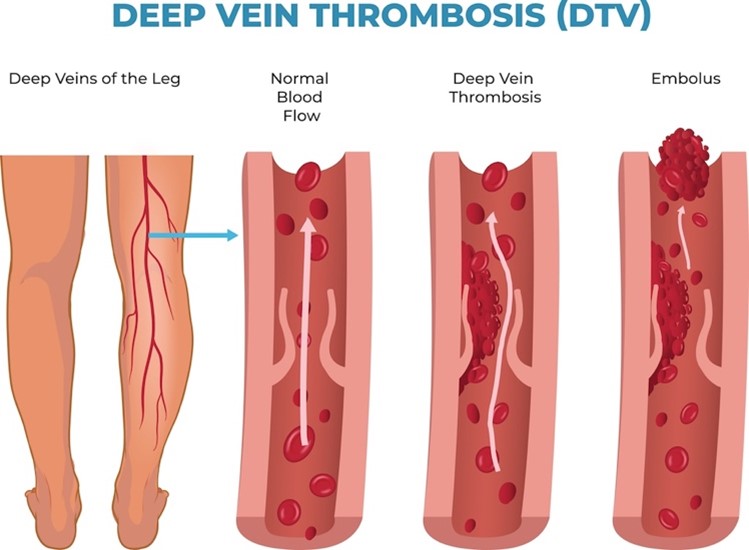

Venous blood flow disorders can result from thromboembolism obstructing the vein, incompetent venous valves, or a reduction in the effectiveness of the pumping action of the muscles. Since venous disorders reduce blood flow and increase venous stasis, this can lead to coagulation defects, edema, tissue breakdown, and increased susceptibility to infection. A decreased venous blood flow will increase venous pressure and hydrostatic capillary pressure. As a result, fluid will move out of the capillaries and into the interstitial spaces, resulting in edema. Edematous tissues are more susceptible to injury, breakdown, and infection since they cannot receive adequate nutrition from the blood. A DVT is a blood clot in a deep vein that more commonly occurs in the lower extremities but occasionally appears in the upper extremities and elsewhere (refer to Figure 1). If the clot breaks free from the wall of the vein and travels to the lungs, it causes a PE by partially or completely blocking the blood flow to the lungs (refer to Figure 1). DVTs found in the thigh are more likely to cause PEs than those found in the lower leg or elsewhere. PEs can lead to pulmonary hypertension, an increase in the blood pressure in the vessels leading to the lungs due to obstructed blood flow. Pulmonary hypertension can lead to heart failure and symptoms such as difficulty breathing, swelling, fatigue, palpitations, and hemoptysis (coughing up blood) (Chaudhry et al., 2022; Hinkle et al., 2021; NHLBI, 2022).

Venous thrombosis can happen in any vein but most commonly occurs in the veins of the lower extremities. The formation of a thrombus frequently accompanies phlebitis (i.e., inflammation of the vein walls). DVTs in the upper extremities occur about 2% of the time, but the incidence may be as high as 65% in patients with central venous cannulation or upper extremity compression. When an upper extremity DVT does develop, it usually involves multiple venous segments, with the subclavian the most commonly affected. Other risk factors for upper extremity DVTs include internal trauma to the vein from the presence of an IV, pacemaker leads, chemotherapy ports, dialysis catheters, or parenteral nutrition lines. Another mechanism for upper extremity DVTs is repetitive motion or effort thrombus formation (i.e., Paget-Schroetter syndrome). Effort thrombosis results when repetitive motion irritates the vessel wall, causing inflammation and subsequent thrombus. Construction workers, competitive swimmers, tennis players, baseball players, and weightlifters are examples of individuals who engage in repetitive...

...purchase below to continue the course

A venous thrombus forms when platelets aggregate and attach to the vein wall. The thrombus has a tail-like appendage containing fibrin and white and red blood cells. Successive layers of the thrombus can form and propagate in the direction of blood flow. The propagating thrombus is dangerous because parts can break off (i.e., emboli) and travel to the pulmonary blood vessels, causing a PE (refer to Figure 1). Fragmentation of the thrombus can occur spontaneously as the thrombus naturally dissolves. Elevated venous pressure can also lead to fragmentation, specifically when engaging in muscular activity after prolonged inactivity. When a DVT occurs, recannulation (i.e., re-establishment of the lumen of the vessel) typically results. PTS is more likely to develop when recannulation does not occur within 6 months of the DVT formation (Chaudhry et al., 2022; Hinkle et al., 2021).

Figure 1

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Embolus

Risk Factors for VTE

Although the exact cause remains unclear, three primary factors play a significant role in the development of VTEs. Collectively, these factors are known as Virchow's triad and include endothelial damage, venous stasis, and altered coagulation (i.e., inherited or acquired). A risk factor for thrombosis can be identified in over 80% of patients with VTE, many of whom have several contributing factors. Endothelial damage (i.e., damage to the intimal lining of the blood vessel) creates a site for a blood clot to form. This damage can occur from trauma (e.g., fractures or dislocations), surgery, pacing wires, central venous or dialysis catheters, local vein damage (e.g., diseases of the vein or chemical irritation from intravenous [IV] medications or solutions), or repetitive motion injuries. Venous stasis occurs when blood pools in the lower extremities. Venous stasis can result from reduced blood flow resulting from conditions such as heart failure or shock. Medications that cause dilation of the veins can also provoke venous stasis. Other risk factors for venous stasis include conditions that decrease skeletal muscle contraction (e.g., immobility, paralysis, or anesthesia), obesity, history of varicosities, prolonged travel, smoking, and being over 65 years of age (Bauer & Lip, 2024; Douketis, 2023; Hinkle et al., 2021; McLendon et al., 2023).

Altered coagulation most commonly affects patients whose anticoagulant medications (e.g., warfarin [Coumadin]) have been abruptly stopped. Other common reasons for hypercoagulability include elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, oral contraceptive use or other oral estrogen therapy (e.g., hormone replacement therapy), and several blood dyscrasias (with prevalence varying by ethnicity). For example, antithrombin III deficiency, protein C deficiency, and protein S deficiency are found primarily in patients of Southeast Asian descent. Factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutation are more common in White individuals, while elevated factor VIII concentrations are more common in Black individuals. These inherited forms of hypercoagulability are rare. Acquired hypercoagulability is far more common, and causes include medications (e.g., testosterone, glucocorticoids, antidepressants, oral contraceptives, estrogen replacement), rheumatologic disease (e.g., lupus), polycythemia vera, and sick cell anemia. Pregnancy is another risk factor for thrombus formation due to increased clotting factors that may remain elevated for more than 6 weeks postpartum. In addition, pregnancy decreases venous flow by 50% due to hormonally decreased venous capacity and reduced venous outflow due to compression from the uterus (Bauer & Lip, 2024; Hinkle et al., 2021; Vaqar & Graber, 2023). The presence of the following factors increases the risk of a VTE in pregnancy:

- previous VTE

- genetic predisposition to or family history of VTE

- diabetes

- varicose veins

- cesarean birth

- inflammatory bowel disease

- gestational age less than 36 weeks

- obstetric hemorrhage

- stillbirth

- smoking

- obesity

- prolonged immobilization

- twin gestation

- older maternal age

- other illnesses during pregnancy (e.g., cancer, infection, or pre-eclampsia; AHA, 2023a; Malhotra & Weinberger, 2024).

The American Heart Association (AHA) also includes chronic medical conditions such as heart disease (i.e., hypertension, dyslipidemia), lung disease (i.e., asthma, obstructive sleep apnea), nephrotic syndrome, stroke, diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disorders in the list of risk factors for a VTE. While all cancers increase the risk for VTE, the risk rises if the cancer is widespread; if it includes the lung, brain, lymph nodes, gynecologic system (e.g., ovarian, or uterine), or gastrointestinal tract (e.g., pancreas or stomach); or if the patient is receiving chemotherapy (i.e., bevacizumab [Avastin], thalidomide [Thalomid]) or surgical intervention. In addition, a lower extremity superficial thrombophlebitis (ST), which consists of a blood clot in a more superficially located vein that causes swelling and/or pain, can also progress to a VTE in some instances if left untreated. Protective factors include maintaining a healthy weight, staying well hydrated, using compression stockings, and staying active or maintaining a healthy level of regular movement (AHA, 2023a, 2023c; Bauer & Lip, 2024; Douketis, 2023; McLendon et al., 2023).

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of a VTE will vary depending on the location and severity of the thrombus. Signs and symptoms of a DVT include lower extremity pain (usually unilateral, which the patient may describe as an ache or cramping), tenderness, swelling, warmth, or redness. In addition, the patient may exhibit a decreased range of motion, an inability to ambulate, or pain that radiates (e.g., from the thigh into the groin). Physical examination of a DVT may reveal dilated superficial veins; unilateral edema with a difference in calf or thigh circumferences; and warmth, tenderness, or erythema. The clinical presentation for PE can vary significantly from no symptoms to sudden death. The most common presenting signs and symptoms include shortness of breath (SOB), tachypnea, chest pain (worsening with deep inhalation), tachycardia, light-headedness/loss of consciousness, irregular heart rate, hemoptysis, hypotension, anxiety/feeling of impending doom, coughing with or without blood, and sweating. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms of PE may also have signs and symptoms of a DVT (AHA, 2023b; Bauer & Huisman, 2024; Thompson et al., 2024; Vaqar & Graber, 2023).

Diagnosis of VTE

An accurate diagnosis is critical due to the morbidity and mortality associated with missed diagnoses and complications of DVT and PE. VTE diagnosis starts with obtaining a comprehensive history of the present illness (i.e., any recent surgery or prolonged immobility due to trauma or illness), past medical history (including any cancer), current medications, and family history. Routine laboratory tests are not diagnostic for VTE but can alter the suspicion of PE, confirm the presence of alternative diagnoses, and provide prognostic information if PE is diagnosed. Complete blood count (CBC), arterial blood gas (ABG), comprehensive metabolic profile (CMP), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), coagulation studies, troponin, and D-dimer (discussed later on) may be ordered. According to the 2018 (last reviewed in 2022) recommendations from the American Society of Hematology (ASH), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American College of Physicians (ACP), the diagnostic algorithm for VTE should begin by assessing the patient's pretest probability (PTP) of VTE with a validated clinical prediction tool. The PTP provides an estimate of the expected prevalence of VTE at the population level. The guideline states that risk should be established with the Modified Wells (Canadian PE) score or the Revised Geneva score. The Modified Wells performs better for pregnant patients and younger patients without comorbidities or a history of VTE (Lim et al., 2018; Ouelette, 2024; Thompson et al., 2024). The Revised Geneva score is reportedly less accurate than the Modified Wells score due to VTE found within the low-risk group of patients at a rate of roughly 8% (score of 0; Ouelette, 2024). For patients with a score that indicates a low PTP, the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) is recommended. This validated scale developed by Kline in 2004 assesses the risk of PE based on eight criteria (Ouelette, 2024; Thompson et al., 2024). If the patient meets all 8 of these criteria, the patient can be safely discharged from the hospital or ED without any further testing recommended. The false-negative rate (the presence of PE despite a negative result on the screen) with this test is less than 1%, with a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 22%. If the PTP is intermediate or low, but the patient does not meet all 8 PERC criteria, further testing with a high-sensitivity D-dimer is recommended. A D-dimer test measures the amount of D-dimer released into the bloodstream when fibrin proteins in a blood clot dissolve. A D-dimer less than 500 ng/mL is considered negative, and no further testing is required. A result over 500 ng/mL is considered positive for the presence of VTE in patients under the age of 50, while a score of age x 10 ng/mL should be used as an age-adjusted cut-off for all patients over the age of 50. ASH guidelines warn against a high rate of false-positive results with D-dimer testing, especially in certain populations such as postsurgical or pregnant patients. The PERC is only valid in clinical settings (typically the ED) with a low prevalence of PE (Lim et al., 2018; Ouelette, 2024; Thompson et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

The ASH guidelines recommend against using a positive D-dimer alone to diagnose DVT in low, intermediate, and high PTP. If a DVT is suspected, the D-dimer should be followed by a lower extremity ultrasound (US) for low-risk patients. Ultrasounds use sound waves to create pictures of blood flow inside the veins. Technicians can also compress the veins during the test to determine if the veins react normally or appear stiff, secondary to the presence of blood clots. If D-dimer testing is not readily available, alternative strategies can include the proximal lower extremity or whole-leg ultrasound alone. The D-dimer may be bypassed in patients with intermediate or high PTP who may undergo US instead. The ASH guidelines also recommend repeating the US if it was initially negative, the PTP is high, and no alternative diagnosis can be found. Many medical centers do not offer 24-hour departmental availability to perform a compressive US. If necessary, the test can be done by an ED physician in under 15 minutes with a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 97%. If the US is negative and a DVT is not ruled out, another alternative is to perform magnetic resonance venography, which is especially helpful for patients who are pregnant or have a BMI over 30, but is not yet validated for routine clinical use (Bates et al., 2018; Bauer & Huisman, 2024; Lim et al., 2018; Tritschler et al., 2018)

For patients with a suspected PE and a low or intermediate PTP, the ASH recommends a strategy that starts with a D-dimer followed by a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan or computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). If a D-dimer is not available, a V/Q scan or CTPA can be performed alone. The ASH guidelines also recommend against using a positive D-dimer alone to diagnose a PE. A V/Q scan is recommended over CTPA for low-intermediate PTP patients due to a lower level of radiation exposure. Reduced radiation exposure is especially important for pregnant patients. A planar lung V/Q scan is a 2-stage radionuclide imaging test that requires the inhalation of radioisotope gas prior to the ventilation portion of the scan, followed by injection of radioisotope albumin intravenously for the perfusion portion to be completed. This test assesses the gas exchange and blood flow within the lungs and surrounding vasculature. CTPA utilizes CT technology and intravenous contrast dye to visualize the lungs and possibly the lower extremities to assess for any blood clots. It is contraindicated in patients with a contrast dye allergy or severe renal impairment. CTPA has better accuracy than planar V/Q scans, is widely available, and easy to perform. The downsides of CTPA include exposure to ionizing radiation at high levels and the need for an intravenous contrast medium (Bates et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2018; Ouelette, 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

If a patient's PTP is assessed as high risk, the ASH guidelines recommend advanced imaging with CTPA and not a V/Q scan. V/Q scintigraphy/single-photon emission CT (SPECT) is a reasonable second choice if CTPA is contraindicated or if CTPA results are negative while suspicion remains high. V/Q SPECT has a similar sensitivity and specificity to CTPA, reduces the patient's radiation exposure, and eliminates the need for contrast. Unfortunately, its safety and efficacy are not yet validated for routine clinical use. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans can also be used to eliminate exposure to radiation and contrast, but have significantly lower accuracy. MRI is inconclusive in up to 19% of suspected PE cases (Bates et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2018; Ouelette, 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

Prevention of VTE

An estimated 50% of hospitalized medical patients are at risk of developing a VTE, and thromboprophylaxis (VTE prophylaxis) is critical to prevent VTEs. Health care professionals (HCPs) should be aware that thromboprophylaxis does not eliminate the risk of VTEs, so diligent assessments are essential to reducing morbidity and mortality. When choosing the appropriate method of primary prophylaxis, HCPs should consider patient demographics, the perceived risk, effectiveness, ease of administration, cost-efficiency, and safety (i.e., risk of bleeding or other complications). VTE prophylaxis can be defined as primary or secondary: primary is preferred over secondary prophylaxis due to its efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Primary prophylaxis consists of pharmacologic (e.g., low molecular weight heparin [LMWH], unfractionated heparin [UFH], fondaparinux [Arixtra], direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs]) or mechanical methods (e.g., compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression [IPCs] devices). In contrast, secondary prevention involves the early detection and treatment of subclinical venous thrombosis. Secondary prevention is done by screening medical patients with objective methods that are sensitive to detecting the presence of a VTE (e.g., venous ultrasound, MRI venography, contrast venography). This approach is not commonly used due to the limited established efficacy of these screening methods. Secondary prevention may be used during pregnancy or when primary prevention is contraindicated (Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024a; Schunemann et al., 2018).

Thrombosis and Bleeding Risk Assessment

Before initiating VTE prophylaxis, HCPs should assess each patient for the risk of thrombosis and bleeding. The risk of VTE depends on the circumstances of the acute illness and the presence of risk factors. Therefore, HCPs should complete a history and physical examination for all patients admitted to the hospital. Medical patients with a single risk factor are considered at risk for VTE. Some of the most common risk factors for medical patients include acute respiratory failure, sepsis, known thrombophilia, previous VTE, age older than 60 years, elevated D-dimer, heart failure, inflammatory bowel disease, and prolonged immobility (i.e., for longer than 3 days). Patients with active cancer, lower limb paralysis (e.g., from a stroke), or critical illness are considered high risk. When pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis is indicated, HCPs should assess the risk of bleeding for all patients. Patients considered high risk for bleeding include those with moderate to severe coagulopathy, active bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, a planned surgical procedure in 6 to 12 hours, severe bleeding diathesis, or severe thrombocytopenia (i.e., platelet count [PLT] < 50,000/µL). Other risk factors for bleeding in hospitalized medical patients include hepatic or renal failure, the presence of an intravenous catheter, rheumatoid arthritis, older age, cancer, intensive care stay, and male sex. Epistaxis and menstrual bleeding are not contraindications for VTE prophylaxis. Validated tools for assessing bleeding risk are lacking or require further evaluation (Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024a; Schunemann et al., 2018).

Long-Distance Travel

Long-distance travel is associated with a small risk for VTE, with the greatest risk of VTE developing within 2 weeks of travel. For individuals traveling long distances (i.e., more than 4 hours), the AHA recommends doing seated ankle/calf exercises, getting up to walk around every 2–4 hours, and staying hydrated (AHA, 2017c). The ASH does not recommend compression stockings or aspirin (ASA) for individuals without increased risk. For individuals with increased risk (defined as a recent history of surgery, prior history of VTE, less than 6 weeks postpartum, current active malignancy, or the presence of two or more risk factors such as hormone replacement therapy, obesity, and pregnancy), the ASH recommends the use of compression stockings, LMWH, or ASA during long-distance travel. Compression stockings and LMWH are the preferred VTE prophylaxis for these individuals. For patients who cannot use compression stockings or LMWH (e.g., aversion to anticoagulants), ASA is recommended versus no prophylaxis (Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024a; Schunemann et al., 2018).

Acutely or Critically Ill Medical Patients

The ASH estimates that approximately 50% of all VTEs occur due to current or recent hospitalization for an acute medical illness or surgery. Hospital-acquired VTEs are preventable using anticoagulants and mechanical devices (e.g., compression stockings and IPC devices). Pharmacological prophylaxis is preferred for acute medical patients admitted to the hospital with an increased VTE risk and acceptable bleeding risk. LMWH or fondaparinux (Arixtra) is preferred over UFH or DOACs due to their once-daily dosing regimen and reduced rate of complications. LMWHs, such as enoxaparin (Lovenox) and dalteparin (Fragmin), are subcutaneous medications that inhibit thrombin and factor Xa. These recommendations also apply to critically ill medical patients with acceptable bleeding risk. The ASH recommends mechanical prophylaxis (e.g., sequential compression device, foot pumps, etc.) instead of pharmaceutical prophylaxis for acute medical patients admitted to hospitals with an increased risk of bleeding. For acutely and critically ill medical patients who do not receive pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (e.g., patient refusal), the ASH recommends mechanical prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis. Treatment with both pharmacological and mechanical prophylaxis is not recommended for acutely or critically ill medical patients (Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024a; Schunemann et al., 2018).

HCPs should check the PLT regularly (i.e., on days 5 and 9) for all patients receiving LMWH to detect potential heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT; Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024a). Although ASA has been shown to reduce the risk of arterial thrombosis, there is little evidence supporting its use to prevent VTEs. Similarly, warfarin (Coumadin) initiation is not recommended for VTE prevention due to its delayed (i.e., 36 to 72 hours) therapeutic anticoagulation effect. In addition, medical patients often have other comorbidities (e.g., impaired liver function) or medications that interfere with the anticoagulation effect (Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024a).

Chronically Ill Medical Patients

The ASH guidelines recommend inpatient-only VTE prophylaxis versus inpatient plus extended outpatient prophylaxis for acutely or critically ill medical patients. However, this recommendation does not apply to patients previously on a DOAC for another indication. For chronic medical inpatients residing in skilled nursing facilities, the guidelines recommend against prophylactic treatment for VTE. The ASH also does not recommend prophylaxis for outpatients with minor provoking risk factors such as prolonged immobility, injury, illness, or infection (Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024a; Schunemann et al., 2018).

Non-Orthopedic Surgical Patients

VTE is common in the postoperative setting, with over 50% of these patients at moderate risk for VTE. Non-orthopedic surgeries involve the skin and soft tissues of the trunk and extremities or surgery involving the abdomen, head, neck, chest, or pelvic organs. Like acutely ill medical patients, HCPs should assess the risk for thrombosis and bleeding. For surgical patients, the risk of VTE depends not only on patient factors but also on the type of procedure. Procedure-related factors that can increase VTE risk include intraoperative positioning, the extent and duration of the procedure (i.e., surgery lasting longer than 2 hours or emergent surgery), the type of anesthesia, and postoperative mobility (more than 4 days of immobilization). Minor procedures done in an ambulatory setting are generally low risk for VTE. Next, HCPs should assess bleeding risk by considering the individual risk factors discussed above. In addition to individual risk factors, bleeding risk for the specific procedure should be considered. Surgical procedures considered low risk for bleeding (less than 2%) include uncomplicated general, abdominal-pelvic, vascular, bariatric, and thoracic surgery. In contrast, cardiac surgery and patients with significant trauma, especially of the brain and spine, are at high risk for bleeding (greater than 3%; Anderson et al., 2019; Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024b).

The ASH guidelines set specific guidelines for the prevention of VTE in surgical patients. For patients undergoing major non-orthopedic surgery, the ASH recommends using pharmacological or mechanical prophylaxis depending on the risk of VTE, the risk of bleeding, and the type of surgical procedure. For patients who receive pharmacologic prophylaxis (LMWH or UFH), a combined approach with pharmacological and mechanical prophylaxis is recommended, especially for patients with a high risk of VTE. The ASH recommends that mechanical prophylaxis should be given to patients who do not receive pharmacologic prophylaxis. When mechanical prophylaxis is used for non-orthopedic surgical patients, the ASH recommends IPC devices over compression stockings. For patients with a high risk for bleeding, mechanical prophylaxis with IPC is recommended. In the 2019 guidelines, the ASH panel also recommended avoiding inferior vena cava (IVC) filters for VTE prophylaxis (Anderson et al., 2019; Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024b).

Orthopedic Surgical Patients

The VTE risk among patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery is the highest among all types of surgery. The risk of VTE and bleeding in orthopedic surgical patients can vary depending on patient-related risk factors and the type of procedure (i.e., elective or emergent, major or minor); therefore, the preferred VTE prophylaxis method should be determined on an individual basis. Like non-orthopedic surgical patients, HCPs should assess the risk of thrombosis and bleeding for orthopedic surgical patients. Orthopedic surgeries considered low risk for VTE include foot and ankle fractures, arthroscopy, and shoulder and elbow surgery. In contrast, hip and knee arthroplasty, pelvic surgery, hip fracture surgery, and multiple fracture surgery are considered high risk for VTE. Procedural factors that can impact VTE risk include the type of anesthesia, the extent and length of surgery, and the likelihood of postoperative immobility. Patient-related factors include the same risk factors identified for non-orthopedic surgery. Additional patient-related risk factors specific to orthopedic surgery include poor ambulation prior to surgery, patients over 75 years old, BMI over 30, and cardiovascular disease. Next, HCPs should assess bleeding risk according to Individual risk factors. Pharmacological prophylaxis is contraindicated for patients with active bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, or a PLT below 50,000/µL (Anderson et al., 2019; Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024c).

Low-Bleeding-Risk Patients

According to the ASH, patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA), total knee arthroplasty (TKA), and hip fracture surgery should receive pharmacological VTE prophylaxis. For patients at low risk of bleeding, pharmacological prophylaxis is recommended for up to 10 to 14 days. The initial pharmacologic agent of choice for THA/TKA patients is LMWH or a DOAC. Mechanical prophylaxis can be combined with pharmacologic agents for orthopedic surgery patients, although limited evidence supports the added benefit of mechanical prophylaxis (Anderson et al., 2019; Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024c).

LMWH has been considered the gold standard for pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis for other major orthopedic surgery patients. Studies have shown that LMWH is more effective than UFH or warfarin (Coumadin) for VTE prevention, but less effective than fondaparinux (Arixtra). The bleeding risk among these agents is similar, except that fondaparinux (Arixtra) has a higher incidence of hemorrhage. Studies have also shown that DOACs, specifically rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis), have similar safety and efficacy profiles as LMWH. The efficacy of ASA is unclear in the initial postoperative period, but clinical evidence does support using ASA for extended prophylaxis (i.e., beyond 5 days). HCPs should be aware that VTE prophylaxis reduces but does not eliminate the risk of VTEs; therefore, diligently assessing and monitoring for clinical manifestations of VTE are essential for patient safety (Anderson et al., 2019; Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024c).

High-Bleeding-Risk Patients

Mechanical prophylactic VTE methods should be used for patients deemed at high risk for bleeding when pharmacologic prophylaxis is contraindicated. Mechanical prophylactic methods for this population include IPC devices, compression stockings, and venous foot pumps (VFPs). Based on the available data, IPC devices are the preferred mechanical method of VTE prophylaxis. The ASH does not recommend the use of IVC filters for VTE prophylaxis. Research has shown that mechanical methods can reduce the risk of asymptomatic VTE by 50% compared to placebo; however, these methods are less effective than LMWH or warfarin (Coumadin). Therefore, if the risk of bleeding decreases, patients should be switched to a pharmacologic agent. Another disadvantage to IPC device use is poor compliance, with under 50% of patients using this approach properly (Anderson et al., 2019; Douketis & Mithoowani, 2024c).

Superficial Thrombophlebitis

Because superficial thrombophlebitis can progress to VTE, many providers believe these cases should be treated to avoid progression. Currently, fondaparinux (Arixtra), dosed prophylactically at 2.5 mg/day subcutaneously for 45 days, has the clearest and most concise evidence for efficacy and safety versus placebo. For patients who refuse or cannot take parenteral anticoagulation, rivaroxaban (Xarelto) 10 mg daily is recommended (Nisio et al., 2018; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024).

Pregnancy

The ASH recommends antepartum prophylaxis with the standard dose of LMWH for women with antithrombin deficiency and a family history of VTE, a homozygous mutation for factor V Leiden, combined thrombophilia, or a personal history of VTE related to a hormonal risk factor or unprovoked VTE who are not currently on long-term anticoagulation treatment. They recommend postpartum prophylaxis with a standard or intermediate dose of LMWH for women with antithrombin deficiency and a family history of VTE, women who are homozygous for factor V Leiden or prothrombin genetic mutation, women with combined thrombophilia, women with a protein C or S deficiency, or women with a personal history of VTE. No prophylaxis is recommended for pregnant women with no or a single clinical risk factor for VTE. The ASH recommends antithrombotic prophylaxis for women undergoing assistive reproductive treatment who develop severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (Bates et al., 2018).

Treatment of VTE

Once a VTE has been diagnosed, numerous options are available for treatment. Benefits of treatment include preventing clot extension, PE, recurrent VTE, hemodynamic collapse, and even death. VTEs are generally categorized as provoked (i.e., related to a specific known risk factor) or unprovoked. Surgical patients who develop VTE postoperatively are considered low risk (less than 1% after a year, 3% after 5 years) for recurrence. Patients with VTE not related to surgery but instead related to pregnancy, prolonged immobility, or exogenous estrogen therapy have an intermediate risk for recurrence (5% after a year, 15% after 5 years). Both low- and intermediate-risk patients can be treated with anticoagulant medication for 3 months. For high-risk patients (those with unprovoked or cancer-related VTE), the risk of recurrence is high. Cancer patients should be treated until remission or for at least 6 months. Patients with unprovoked VTE should be treated indefinitely if their bleeding risk is low to intermediate, or for 3–6 months if they have a high risk for bleeding; this is especially important for those assigned male at birth, who have twice the risk of recurrence compared to patients assigned female at birth (Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

Serial Surveillance

In symptomatic, isolated distal DVT cases without severe symptoms, the 2021 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guideline update recommends serial ultrasound surveillance (i.e., 2 weeks) for an extension to the proximal veins over anticoagulation for low-risk patients (e.g., postoperative provoked VTE). A meta-analysis of patients with distal DVT showed a potentially decreased recurrence rate among those treated with anticoagulants, but this was based on limited evidence. The only double-blind, randomized clinical trial on this topic showed that 6 weeks of LMWH was not superior to placebo for low-risk patients as far as the proximal extension of the clot, development of a contralateral DVT, or development of a symptomatic PE; the LMWH group also had an increased risk of bleeding. Anticoagulation is recommended over serial imaging for acute isolated distal DVT of the leg with severe symptoms or risk factors for an extension. If thrombus extension occurs in patients receiving serial imaging, anticoagulation should be initiated (Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

Nonpharmacological and Procedural Treatment Options

Compression stockings are recommended only for symptomatic relief of swelling and discomfort. Catheter-directed thrombolysis should be performed in cases of threatened limb loss. A combination of thrombolysis and an anticoagulant compared to anticoagulants alone reduced the risk of PTS by one-third but had no significant effect on the risk of PE, recurrent DVT, or death; the thrombolysis group also had an increased risk of bleeding. The recent ATTRACT trial compared thrombolysis to anticoagulants and found that the thrombolysis group had an increased risk of major bleeding in the first 10 days and equivalent rates of PTS at 24 months, VTE recurrence, and mortality compared with those patients in the medication group. The ASH guidelines recommend anticoagulation alone instead of anticoagulation and thrombolysis for most patients. For patients with hemodynamic compromise, the ASH recommends thrombolysis followed by anticoagulation. IVC filters are only recommended for patients with an absolute contraindication to pharmacological anticoagulation and proximal DVT or PE. Their use has become controversial due to an increased mortality rate in the first 30 days following placement. A recent trial comparing IVC filters with anticoagulants versus anticoagulants alone found no reduction in recurrent PE or death at 3–6 months in the combination treatment group (Ortel et al., 2020; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

Pharmacological Treatment

The 2018 (reviewed in 2022) ASH guidelines do not specify which medication is preferred for VTE treatment but instead give guidelines regarding the groups of medications available. All patients on anticoagulants should receive additional supplementary patient education. The ASH recommends against the use of a daily lottery to improve medication adherence, as evidence has not shown them to be effective. Instead, the ASH recommends ensuring access to providers across the care continuum, including team-based care, and reducing barriers to obtaining medications, such as costs. In addition, the ASH recommends using health information technology to improve communication and medication adherence (Witt et al., 2018).

In general, the 2022 ACCP guidelines and the 2019 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend the use of DOACs over other medications as they are non-inferior in terms of efficacy with an improved safety profile based on a reduced risk of major bleeding as compared to a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) such as warfarin (Coumadin). They also carry the advantage of rapid onset of action and predictable pharmacokinetic profile, which negates the need for monitoring and dose adjustments. For dabigatran (Pradaxa) or edoxaban (Savaysa, an oral factor Xa inhibitor), they recommend using LMWH for at least 5 days first; when administering rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis), antecedent LMWH is not necessary (Konstantinides & Meyer, 2019; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018; Witt et al., 2018).

For patients on a VKA, the guidelines suggest home point-of-care INR testing (patient self-testing or PST) and self-adjusting of dose (patient self-management or PSM) for competent and capable patients. INR testing should be done every 4 weeks or fewer after initiation and dose adjustments, and every 6–12 weeks when dosing is stable. They suggest using an anticoagulant management service (AMS) in a specialized clinic over a primary care clinic when available. For patients on a VKA with a low to moderate risk of recurrent VTE who require a planned invasive procedure, no perioperative bridging with UFH or LMWH is recommended (Konstantinides & Meyer, 2019; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018; Witt et al., 2018).

Renal Failure

As previously mentioned, LMWH and many DOACs are excreted renally. VKAs are still recommended by the ACCP/ESC for patients with severe renal impairment. For those on LMWH with severe renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min), dosing should be adjusted based on the package insert instructions rather than on anti-factor Xa concentration monitoring. For patients with mild renal impairment (creatinine clearance >49 mL/min), they recommend monitoring renal function every 6–12 months. Those with moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30–50 mL/min) should be monitored every 3 months (Konstantinides & Meyer, 2019; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018; Witt et al., 2018)

Ante and Postpartum Patients

VTE complicates approximately 1.2 of every 1,000 deliveries in the United States. the ASH recommends LMWH over UFH for the treatment of acute VTE or superficial vein thrombosis for pregnant patients. As with other patients, the ASH does not recommend monitoring of anti-factor Xa for dosing. Catheter-directed thrombolysis is not recommended for pregnant patients with acute lower extremity DVTs. If a patient is on LMWH at a therapeutic dose, the ASH suggests stopping the anticoagulant medication prior to scheduled delivery. They suggest this is unnecessary for women on the lower prophylactic dose of LMWH. Avoid the use of DOACs for breastfeeding mothers and opt for UFH, LMWH, VKA, or fondaparinux (Arixtra; Bates et al., 2018).

Pediatric Patients

VTE affects children at a rate of 0.07–0.14 per 10,000 children, but among hospitalized patients, this rate increases to 58 per 10,000. The ASH suggests that asymptomatic VTE should not be treated, but encourages treatment with LMWH or VKA for symptomatic cases. Treatment is recommended for a maximum of 3 months for cases of DVT or provoked PE, or for 6–12 months in the case of unprovoked PE. Thrombolysis is suggested for PE with hemodynamic instability, followed by anticoagulant therapy, but not in cases of DVT or sub-massive PE. Thrombolysis may also be indicated for pediatric patients with life-threatening renal vein thrombosis. Thrombectomy is not recommended for pediatric patients, and neither are IVC filters. Treatment with anticoagulant medication is recommended for children with right atrial thrombosis, renal vein thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis (with occlusive thrombus, post–liver transplant, or idiopathic), or cerebral sinovenous thrombosis. No anticoagulation is recommended for children with portal vein thrombosis with nonocclusive thrombus or portal hypertension. For children with congenital purpura fulminans related to homozygous protein C deficiency, the ASH recommends protein C replacement with or without liver transplantation. Antithrombin replacement treatment is not recommended for pediatric patients unless they fail to respond to standard anticoagulation medication, and their antithrombin levels are low when tested. Central venous access devices do not have to be removed until after treatment has been initiated if the devices are still functioning and required for treatment purposes (Monagle et al., 2018).

Cancer Patients

Cancer patients who develop VTE have an especially high risk of recurrence and bleeding complications. Cancer patients have a 15% VTE recurrence rate and should be treated until remission or for at least 6 months. The ACCP update recommends that for patients with an acute VTE (cancer-associated thrombosis), an oral Xa inhibitor (e.g., apixaban [Eliquis], edoxaban [Savaysa], rivaroxaban [Xarelto]) should be initiated over LMWH for the treatment phases of therapy. Edoxaban (Savaysa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) have a higher risk for major GI bleeding in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis and gastrointestinal malignancy, so apixaban (Eliquis) or LMWH is preferred for these patients (Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024).

Unprovoked VTE

Patients with unprovoked episodes of VTE (no identifiable risk factor or trigger present at the time of diagnosis) and low to moderate bleeding risk should receive long-term treatment to prevent a recurrence. Patients with unprovoked VTE have a 10% risk of recurrence after a year and 30% after 5 years. Serial D-dimer testing may be acceptable for those assigned female at birth, as they have a lower risk of recurrence than those assigned male at birth, and for patients with increased bleeding risk or other contraindications to anticoagulant medications. Another option for those assigned female at birth with an unprovoked VTE is to calculate their risk of recurrence using the Hyperpigmentation, Edema, Redness, D-dimer, Obesity, Older age 2 (HERDOO2) score. Originally developed in 2008, this score attempts to identify the low-risk group of patients who may be safe to discontinue anticoagulant therapy after the acute treatment phase for a single unprovoked VTE (Konstantinides & Meyer, 2019; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018). The patient receives a point for each of the following risk factors:

- signs/symptoms of PTS in either lower extremity (hyperpigmentation, redness, or edema)

- D-dimer over 249 µg/L while taking an anticoagulant for at least 6 months

- BMI over 29

- age older than 64.

If a patient has a score of 0–1, they are considered at low risk for VTE recurrence according to the HERDOO2 developers, and discontinuation of the anticoagulant medication could be considered. If a patient's score is 2 or above, medication should be continued. The 2022 ACCP and 2019 ESC guidelines recommend treatment with a DOAC for patients without cancer instead of a VKA or ASA. DOACs have equivalent effectiveness and a reduced risk of bleeding compared to VKAs and superior effectiveness compared to ASA. DOACs are typically more expensive than VKAs, and there is no evidence for their use in patients with significant renal impairment (CC <30 mL/min), antiphospholipid syndrome, HIT, or a VTE in an unusual site (e.g., the splanchnic vein). For patients with unprovoked VTEs, offering extended-phase anticoagulation (i.e., 6 months or indefinite) is recommended. The 2022 ACCP guidelines recommend extended-phase anticoagulation with a DOAC (or VKA for patients who cannot receive a DOAC). A reduced dose of apixaban (Eliquis) or rivaroxaban (Xarelto) is recommended over full doses for extended-phase anticoagulation (Konstantinides & Meyer, 2019; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

Pulmonary Embolism

Systemic thrombolysis is currently the initial treatment of choice for patients with acute massive or high-risk PE (with hemodynamic compromise or instability, such as a systolic blood pressure <90), according to the 2022 ACCP and 2019 ESC guidelines. This treatment carries an increased risk of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage, and is not recommended for intermediate-risk patients. In a recent study, intravenous heparin combined with systemic thrombolysis reduced the risk of recurrent PE but increased the risk of major bleeding when compared with intravenous heparin alone. Therefore, this treatment is only recommended by the ASH for patients with life-threatening hemodynamic instability, especially for pregnant patients with VTE (Bates et al., 2018; Konstantinides & Meyer, 2019; Stevens et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2024; Tritschler et al., 2018).

Management of Complications

As with most medications and medical treatments, complications may arise with the use of anticoagulant medications. For anticoagulant therapy, the primary potential complication is bleeding. The ASH has some general guidelines regarding the management of this complication. For patients on a VKA, complications may begin with an unsafe/highly elevated INR (>4.5), leading to dangerous bleeding. For patients with an INR 4.5–10 without any clinically relevant bleeding, they suggest stopping the medication but do not recommend administering vitamin K. In the case of life-threatening bleeding, they recommend administering vitamin K along with 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCCS) as opposed to fresh frozen plasma (Tritschler et al., 2018; Witt et al., 2018).

For patients on a DOAC, the ASH recommends against measuring their effect during the management of heavy bleeding. If these patients develop life-threatening bleeding, the ASH recommends stopping the anticoagulant medication and administering 4-factor PCCS or coagulation factor Xa (recombinant) or inactivated-zhzo (andexanet alpha or Andexxa) if on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), edoxaban (Savaysa), or apixaban (Eliquis). In contrast, the ACCP/ESC guidelines state that andexanet alpha (Andexxa) should be used to reverse apixaban (Eliquis) or rivaroxaban (Xarelto) in cases of life-threatening bleeding but do not mention its use for patients taking edoxaban (Savaysa). For most mild-to-moderate bleeding cases that are not life-threatening, the ACCP/ESC guidelines recommend simply stopping the medication and supportive care due to their short half-life. Patients on dabigatran (Pradaxa) who develop life-threatening bleeding should stop the medication and receive the reversal agent idarucizumab (Praxbind). The guidelines suggest restarting oral anticoagulants within 90 days of major bleeding for patients with a moderate to high risk of recurrent VTE and a low to moderate risk of recurrent bleeding. For patients on UFH or LMWH who develop life-threatening bleeding, the ASH recommends stopping the anticoagulant and administering protamine (Tritschler et al., 2018; Witt et al., 2018).

Outside of bleeding, a potential complication of using UFH and, to a lesser degree, LMWH or fondaparinux (Arixtra), is the development of HIT. This syndrome is a prothrombotic adverse drug reaction mediated by IgG antibodies that target platelet factor 4 and heparin complexes. The ASH defines the following patients as low risk for developing HIT: medical or obstetric patients or patients following minor surgeries or trauma on LMWH or fondaparinux (Arixtra). Patients on LMWH or fondaparinux (Arixtra) following major surgery or trauma or medical/obstetric patients on UFH are considered at intermediate risk for HIT. Patients on UFH after major surgery or trauma are defined as high risk for the development of HIT. Patients at low risk for HIT require no PLT monitoring. For intermediate- or high-risk patients, the ASH recommends monitoring PLT on day 0 if the patient has a history of heparin use in the last 30 days, or on day 4 if there has been no recent heparin use. After this, the ASH recommends checking PLT every 2–3 days thereafter (intermediate risk) or every other day (high risk). The 4T score assesses a patient's PTP of HIT. A score of 0–3 indicates low risk, 4–5 indicates intermediate risk, and 6–8 indicates high risk for HIT. Points are assigned for the degree of thrombocytopenia, the timing of thrombocytopenia, the presence of thrombosis, and the presence of an alternative cause of thrombocytopenia (Cuker et al., 2018).

Immunoassays and/or functional assays are typically used to confirm a diagnosis of HIT. In acute HIT (when the diagnosis has been confirmed, but PLT remains low), heparin is contraindicated. An alternative anticoagulant should be started, such as argatroban (Acova, a direct thrombin inhibitor given intravenously with a shorter duration that should be avoided in patients with hepatic dysfunction), bivalirudin (Angiomax, another direct thrombin inhibitor given intravenously), fondaparinux (Arixtra), or a DOAC. VKAs are not recommended until a patient's PLT count has recovered to over 150,000/mL. IVC filters are not recommended, and antiplatelet medication is unnecessary unless a patient also has coronary artery disease, a cardiac stent, or some other indication for antiplatelet medication. Platelet infusion is only recommended for actively bleeding or high-risk patients. For patients who require dialysis during acute HIT, the ASH recommends using argatroban (Acova) or bivalirudin (Angiomax) to prevent thrombosis of the circuitry (Cuker et al., 2018).

The ASH suggests a bilateral lower extremity US to screen for lower extremity thrombosis and an upper extremity US for patients with a central venous catheter in place. For patients with isolated HIT and no associated DVT, anticoagulants should be continued until the PLT count recovers, but not for longer than 3 months. During those 3 months, the ASH recommends that patients wear an emergency alert bracelet warning medical providers of their recent history of HIT. In the case of life- or limb-threatening thrombosis, the ASH recommends a parenteral medication instead of an oral option (Cuker et al., 2018).

Subacute HIT A refers to the period when the patient's PLT count has recovered, but immunoassays remain positive. During this period, the ASH recommends treatment with a DOAC instead of a VKA. Subacute HIT B refers to the period when a patient's functional assay has returned to normal, but the immunoassay remains positive for HIT. Remote HIT refers to the period following HIT when all lab values have returned to normal. The ASH recommends waiting until the Subacute B or remote stage before proceeding for patients who require cardiovascular surgery. According to the ASH, patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention should receive bivalirudin (Angiomax) as the anticoagulant of choice. For patients with a remote history of HIT who require VTE treatment, UFH and LMWH are not recommended; argatroban (Acova), fondaparinux (Arixtra), or a DOAC are safer options. For patients requiring dialysis during subacute or remote HIT, the ASH recommends regional citrate to prevent thrombosis of the circuitry (Cuker et al., 2018).

References

American Heart Association. (2023a). Risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE). https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/venous-thromboembolism/risk-factors-for-venous-thromboembolism-vte

American Heart Association. (2023b). Symptoms and diagnosis of venous thromboembolism (VTE). https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/venous-thromboembolism/symptoms-and-diagnosis-of-venous-thromboembolism-vte

American Heart Association. (2023c). What is venous thromboembolism (VTE)? https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/venous-thromboembolism/what-is-venous-thromboembolism-vte

Anderson, D. R., Morgano, G. P., Bennett, C., Dentali, F., Francis, C. W., Garcia, D. A., Kahn, S. R., Rahman, M., Rajasekhar, A., Rogers, F. B., Smythe, M. A., Tikkinen, K. A. O., Yates, A. J., Baldeh, T., Balduzzi, S., Brozek, J. L., Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I., Johal, H., Neumann, I., . . . Dahm, P. (2019). American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Advances, 3(23), 3898–3944. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000975

Bates, S. M., Rajasekhar, A., Middeldorp, S., McLintock, C., Rodger, M. A., James, A. H., Vazquez, S. R., Greer, I. A., Riva, J. J., Bhatt, M., Schwab, N., Barrett, D., LaHaye, A., & Rochwerg, B. (2018). American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Venous thromboembolism in the context of pregnancy. Blood Advances, 2(22), 3317–3359. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024802

Bauer, K. A., & Huisman, M. V. (2024). Clinical presentation and diagnosis of the nonpregnant adult with suspected deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity. UpToDate. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-the-nonpregnant-adult-with-suspected-deep-vein-thrombosis-of-the-lower-extremity

Bauer, K. A., & Lip, G. Y. H. (2024). Overview of the causes of venous thrombosis. UpToDate. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-causes-of-venous-thrombosis

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). About venous thromboembolism (blood clots). https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/about

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). Data and statistics on venous thromboembolism. https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/data-research/facts-stats

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). Understanding your risk for healthcare-associated VTE (blood clots). https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/risk-factors/ha-vte.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/ha-vte.html

Chaudhry, R., Miao, J. H., Rehman, A. (2022). Physiology, cardiovascular. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493197

Cuker, A., Arepally, G. M., Chong, B. H., Cines, D. B., Greinacher, A., Gruel, Y., Linkins, L. A., Rodner, S. B., Selleng, S., Warkentin, T. E., Wex, A., Mustafa, R. A., Morgan, R. L., Santesso, N. (2018). American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood Advances, 2(22), 3360–3392. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024489

Douketis, J. D. (2023). Deep venous thrombosis (DVT). https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/cardiovascular-disorders/peripheral-venous-disorders/deep-venous-thrombosis-dvt

Douketis, J. D., & Mithoowani, S. (2024a). Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease in acutely ill hospitalized medical adults. UpToDate. Retrieved December 10, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-venous-thromboembolic-disease-in-acutely-ill-hospitalized-medical-adults

Douketis, J. D., & Mithoowani, S. (2024b). Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease in adult nonorthopedic surgical patients. UpToDate. Retrieved December 12, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-venous-thromboembolic-disease-in-adult-nonorthopedic-surgical-patients

Douketis, J. D., & Mithoowani, S. (2024c). Prevention of venous thromboembolism in adults undergoing hip fracture repair or hip or knee replacement. UpToDate. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-venous-thromboembolism-in-adults-undergoing-hip-fracture-repair-or-hip-or-knee-replacement

Gregson, J., Kaptoge, S., Bolton, T., Pennells, L., Willeit, P., Burgess, S., Bell, S., Sweeting, M., Rimm, E. R., Kabrhel, C., Zoller, B., Assmann, G., Gudnason, V., Folsom, A. R., Arndt, V., Fletcher, A., Norman, P. E., Nordestgaard, B. G., Kitamura, A., . . . Meade, T. (2019). Association of cardiovascular risk factors with venous thromboembolism. JAMA Cardiology, 4(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4537

Hinkle, J. L., Cheever, K. H., & Overbaugh, K. (2021). Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of medical-surgical nursing (15th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Konstantinides, S. V., & Meyer, G. (2019). The 2019 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. European Heart Journal, 40(42), 3453–3455. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz726

Lim, W., Le Gal, G., Bates, S. M., Righini, M., Haramati, L. B., Lang, E., Kline, J. A., Chasteen, S., Snyder, M., Patel, P., Bhatt, M., Patel, P., Braun, C., Begum, H., Wiercioch, W., Schunemann, H. J., & Mustafa, R. A. (2018). American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Advances, 2(22), 3226-3256. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024828

Malhotra, A., & Weinberger, S. E. (2024). Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. UpToDate. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/venous-thromboembolism-in-pregnancy-epidemiology-pathogenesis-and-risk-factors

McLendon, K., Goyal, A., & Attia, M. (2023). Deep venous thrombosis risk factors. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470215

Monagle, P., Cuello, C. A., Augustine, C., Bonduel, M., Brandao, L. R., Capman, T., Chan, A. K. C., Hanson, S., Male, C., Meerpohl, J., Newall, F., O'Brien, S. H., Raffini, L., van Ommen, H., Wiernikowski, J., Williams, S., Bhatt, M., Riva, J. J., Roldan, Y., . . . Vesely, S. K. (2018). American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Treatment of pediatric venous thromboembolism. Blood Advances, 2(22), 3292–3316. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024786

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022). Venous thromboembolism. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/venous-thromboembolism

Nisio, M. D., Wichers, I., & Middeldorp, S. (2018). Treatment of lower extremity superficial thrombophlebitis. JAMA, 320(22), 2367–2368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16623

Ortel, T. L., Neumann, I., Ageno, W., Beyth, R., Clark, N. P., Cuker, A., Hutten, B. A., Jaff, M. R., Manja, V., Schulman, S., Thurston, C., Vedantham, S., Verhamme, P., Witt, D. M., Florez, I. D., Izcovich, A., Nieuwlaat, R., Ross, S., Schunemann, H. J., . . . Zhang, Y. (2020). American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Advances, 4(19), 4693–4738. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001830

Ouellette, D. R. (2024). Pulmonary embolism clinical scoring systems. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1918940-overview#a2

Schunemann, H. J., Cushman, M., Burnett, A. E., Kahn, S. R., Beyer-Westendorf, J., Spencer, F. A., Rezende, S. M., Zakai, N. A., Bauer, K. A., Dentali, F., Lansing, J., Balduzzi, S., Darzi, A., Morgano, G. P., Neumann, I., Nieuwlaat, R., Yepes-Nunez, J. J., Zhang, Y., & Wiercioch, W. (2018). American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Advances, 2(22), 3198–3225. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

Stevens, S. M., Woller, S. C. Baumann Kreuzinger, L., Bounameaux, H., Doerschug, K., Geersing, G-J., Huisman, M. V., Kearon, C., King, C. S., Knighton, A. J., Lake, E., Murin, S., Vintch, J. R. E., Wells, P. S., & Moores, L. K. (2022). Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest, 160(6), E545–E608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055

Stevens, S. M., Woller, S. C., Baumann Kreuziger, L., Doerschug, K., Geersing, G-J., Klok, F. A., King, C. S., Murin, S., Vintch, J. R. E., Wells, P. S., Wasan, S., & Moores, L. K. (2024). Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Compendium and review of CHEST guidelines 2012–2021. Chest, 166(2), 388-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2024.03.003

Thompson, B. T., Kabrhel, C., & Pena, C. (2024). Clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnosis of the nonpregnant adult with suspected acute pulmonary embolism. UpToDate. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-evaluation-and-diagnosis-of-the-nonpregnant-adult-with-suspected-acute-pulmonary-embolism

Tritschler, T., Kraaiipoel, N., Gal, G. L., & Wells, P. S. (2018). Venous thromboembolism: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA, 320(15), 1583–1594. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14346

Vaqar, S., & Graber, M. (2023). Thromboembolic event. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549877

Witt, D. M., Nieuwlaat, R., Clark, N. P., Ansell, J., Holbrook, A., Skov, J., Shehab, N., Mock, J., Myers, T., Dentali, F., Crowther, M. A., Agarwal, A., Bhatt, M., Khatib, R., Riva, J. J., Zhang, Y., & Guyatt, G. (2018). American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Advances, 2(22), 3257–3291. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024893