About this course:

This course reviews nationwide and worldwide statistics regarding immunizations and their efficacy in reducing morbidity and mortality. In addition, this course reviews the recommended immunization schedules for children and adults in the United States, including contraindications and safety considerations with pregnancy. Finally, this course reviews the use of immunizations for worldwide epidemics and discusses the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy.

Course preview

CDC Immunization Schedule and the Facts About Vaccines

This course reviews nationwide and worldwide statistics regarding immunizations and their efficacy in reducing morbidity and mortality. In addition, this course reviews the recommended immunization schedules for children and adults in the United States, including contraindications and safety considerations with pregnancy. Finally, this course reviews the use of immunizations for worldwide epidemics and discusses the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy.

After this activity, learners will be prepared to:

- recall the current nationwide and worldwide statistics regarding immunizations.

- identify examples of the efficacy of immunizations in reducing morbidity and mortality.

- describe the components of the recommended immunization schedules for children and adults in the United States.

- discuss the safety of various immunizations during pregnancy.

- describe the use of immunizations in worldwide epidemics such as dengue fever, malaria, and cholera.

- discuss the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy and the myths surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine.

The World Health Organization (WHO) asserts that immunizations or vaccines (these terms will be used interchangeably throughout this learning activity) are the most cost-effective health interventions. There are currently vaccines available for more than 20 life-threatening diseases; these vaccines help to prevent and control infectious disease outbreaks. Immunizations prevent 3.5–5 million deaths per year worldwide, and if global coverage increases, it is predicted that an additional 1.5 million deaths could be prevented. Expanding access to immunizations is critical to preventing sickness and death associated with infectious diseases such as polio, tetanus, whooping cough, and measles. However, it is estimated that 1 in 5 children do not have access to lifesaving vaccines. Over the last decade, immunization rates had plateaued and then dropped between 2019 and 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic was a significant contributor to the setback in immunization coverage rates due to significant disruptions in the health care system, contributing to missed vaccines. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has ended, immunization numbers have not recovered to pre-pandemic rates. For example, global immunization coverage for children receiving the first dose of the measles vaccine dropped from 86% in 2019 to 83% in 2023. In addition, in 2023, it was estimated that 14.5 million children worldwide had not received any vaccination (termed zero-dose children). This is 2.7 million more children than in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly 50% of zero-dose children live in low- and middle-income countries, such as Angola, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sudan, and Yemen (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024j; WHO, n.d.-b, 2019, 2024d). Healthcare providers (HCPs) should be aware of the following terminology pertinent to the topic of immunization coverage:

- A vaccine is a preparation used to stimulate the immune response against disease. These are usually administered through intramuscular injection, but some can be administered orally or nasally.

- Vaccination refers to the act of introducing the vaccine into the body.

- Immunization refers to how a person becomes protected (i.e., through vaccination) from a specific disease. Immunization is often used interchangeably with vaccination or inoculation.

- Immunity refers to protection from an infectious disease (i.e., you can be exposed without becoming infected; CDC, 2024i).

Background and Global Data

Vaccines can prevent various illnesses and diseases, from influenza and pneumonia to cervical cancer and paralysis related to polio. Polio, for example, was once a highly infectious viral disease that could cause irreversible paralysis. Globally targeted for eradication, polio has been nearly eliminated through immunization efforts, existing now in just a few small regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan. However, until polio transmission is interrupted in these countries, all countries remain at risk due to travel links to endemic areas. In addition, only 83% of infants worldwide received three doses of the polio vaccine in 2023. Vaccination rates vary by region, with the European region estimated to have 89% coverage, while the Southeast Asia region has only 6% coverage (WHO, 2024d).

Tetanus is caused by a bacterium that can grow from spores of C. tetani, which is present in the environment. The toxin produced can cause severe complications and death. Infection risk persists as a public health problem in 10 countries, mainly in Asia and Africa. In 2023, approximately 14.5 million infants did not receive an initial dose of the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccine, and an additional 6.5 million were only partially vaccinated. Lack of access to immunizations and other health services persists, as 60% of these 21 million infants live in those same 10 countries (WHO, 2024d).

The effectiveness of immunizations varies from vaccine to vaccine and from condition to condition. As stated above, some vaccines (e.g., polio) are very effective at eradicating the disease. Others are adjunctive tools in a large public health toolbox. For example, meningitis A is an infection that can cause severe brain damage and death. Prior to 2010, Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A (NmA) accounted for 80-85% of meningitis epidemics in Africa. The meningitis A vaccine, introduced in 2010 in Africa south of the Sahara, has nearly eliminated that infection in less than 10 years. By the end of 2023, nearly 350 million individuals in 24 of the 26 countries in the African meningitis belt were vaccinated. However, the meningitis A vaccine is not being consistently integrated into routine worldwide immunization programs. Measles is a highly contagious virus that causes high fevers and rash and can lead to disability, infection, and death (WHO, 2024d). The measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine is very effective; after receiving both doses, the vaccine is 97% effective at preventing measles. Individuals who receive both doses are considered immune for life against measles and rubella (CDC, 2021b).

The WHO estimates that 300,000 children under the age of 5 die from Streptococcus pneumoniae each year worldwide, mostly in developing countries. The original vaccine against S. pneumoniae, the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7), was introduced in the United States in 2000 and in Africa in 2009. The vaccine was upgraded to include more serotypes, renamed PCV13, and reintroduced in 2010/2011. In 2022, PCV15 and PCV20 were approved for use in adults 19 years and older. Rates of pneumococcal infections in South Africa in children under the age of two decreased from 54.8 cases per 100,000 person-years before the vaccination (2005–2008) to just 17 cases per 100,000 person-years after (2011-2012) thanks to a vaccination coverage of 81% in 2012. Despite progress, only 65% of countries have a third-dose pneumococcal vaccine. There is also significant coverage variation, with the European region having 86% coverage and 26% in the Western Pacific region (CDC, 2024n; von Gottberg et al., 2014).

The introduction of new vaccines can be measured in fundamental shifts or changes in medical care trends and outcomes. For example, the varicella vaccine (Varivax or VAR) was introduced in the United States in 1995, with 89% vaccine coverage nationwide by 2006. Zostavax (ZVL) was a live attenuated vaccine introduced in 2006 for herpes zoster or shingles, a secondary infection related to the same virus. The...

...purchase below to continue the course

Closer to home, two separate studies have shown encouraging trends related to cervical cancer since the 2006 introduction of the controversial vaccination for human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract; it can cause genital warts and cervical cancer. A retrospective cohort study between 2007 and 2014 across 16 clinics serving predominantly low-income and underrepresented racial and ethnic populations showed a decrease in abnormal cervical cytology. The detection rate for vaccinated girls (at least one dose, ages 11–20) decreased to 79.1 per 1000 person-years versus 125.7 per 1000 person-years amongst those not vaccinated. This effectiveness was most apparent among those who initiated the vaccine series between the recommended ages of 11-14 and received all three doses (Hofstetter et al., 2016). Similarly, Benard and colleagues (2017) found a decrease in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) amongst girls aged 15-19 in New Mexico over the same period. The incidence per 100,000 patients screened decreased from 3,468.3 in 2007 to 1,590.6 in 2014 for CIN1, from 896.4 to 414.9 for CIN2, and 240.2 to 0 for CIN3. The researchers found a similar significant decrease in CIN2 lesions amongst patients ages 20–24 but an increase in CIN1 and CIN3 lesions amongst patients aged 25–29, who would not have benefited from vaccination before age 14 as recommended (Benard et al., 2017). Although research has supported the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine, many countries have not included the vaccine in routine vaccination panels. More recently, several large countries have included a one-dose schedule HPV vaccine into existing vaccination programs. In 2023, 37 countries instituted a one-dose schedule. This represents approximately 45% of girls aged 9–14 vaccinated in that year. Global coverage with the first dose of the HPV vaccine is now 27%, up from 20% in 2022. (WHO, 2024d).

In 2019, a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified In Wuhan, China. In 2020, the WHO named this disease COVID-19 as it quickly spread worldwide, resulting in a global pandemic. By the end of 2020, several vaccines became available worldwide to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. All the available vaccines were effective in reducing the risk of COVID-19, specifically reducing the risk of severe disease, hospitalization, and death. Even with the emergence of new variants, the COVID-19 vaccines mitigate the risks of severe disease. Numerous clinical trials have reported on the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of the various COVID-19 vaccines; however, there is limited research comparing the efficacy of the vaccines to each other. Currently, there are two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech) and one protein subunit vaccine (Noravax) available. All three vaccines have demonstrated efficacy against COVID-19, and the determination of which vaccine to choose can be patient-specific. When considering adverse effects, the protein subunit vaccine has been associated with thrombosis with thrombocytopenia and Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), whereas the mRNA vaccines have been associated with myocarditis. The risk of these events is minimal (CDC, 2024h; Edwards & Orenstein, 2025; WHO, 2024b).

National Data

The CDC publishes vaccination data from the National Immunization Survey-Child (NIS-Child) for children by age 24 months in the United States. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) currently recommends that by 24 months of age, children should be vaccinated against 15 potentially serious illnesses. In their latest publication, the CDC reported that vaccination rates of children born in 2020–2021 had declined compared to those born pre-pandemic in 2018-2019. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination rates had remained stable; this data demonstrates the impact the pandemic had on vaccination rates for children born in 2020–2021. This decline in coverage occurred across all recommended vaccines (except for the HepB birth dose and two or more doses of HepA), with declining rates ranging from 1.3 to 7.8 percentage points. Despite the declining vaccination rates, coverage for some vaccines remained above 90%, including IPV, MMR, and HepB series. In addition, the percentage of children who received no vaccinations by 24 months remained low (1.2%). The vaccines that had the greatest drop in coverage were two or more doses of influenza and vaccines with a recommended series completion during the second year of life (i.e., fourth dose of DTaP, final dose of Hib, and fourth dose of PCV). The latest report also highlights that disparities still exist based on race, ethnicity, health insurance coverage, poverty, and geographic location. Coverage with 4 of the 17 recommended vaccine measures was lower among non-Hispanic Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native children compared to non-Hispanic White children. Coverage was also lower in children covered by Medicaid or other nonprivate insurance, uninsured children, children living in rural areas, and those living below the federal poverty level (Hill et al., 2024).

Principles of Immunization

Immunization is a vital part of public health and disease prevention, significantly contributing to increased life expectancy and improved quality of life (QOL). The first vaccine was administered in 1796 when a 13-year-old boy was inoculated with cowpox, resulting in immunity to smallpox. Smallpox was globally eradicated in 1979 because of immunization. Knowing how the body fights infections is important to understanding how vaccines work. Once a pathogen invades, the body activates defenses to protect itself from the foreign object and kill the pathogen. The invasion and multiplication of foreign materials eventually lead to an active infection. As a result, the body produces and releases different cells designed to combat the disease. The main components of the immune response come from white blood cells such as macrophages, B-lymphocytes, and T-lymphocytes. Macrophages are phagocytic, engulfing and digesting foreign material, including pathogens. A small portion of the pathogen, known as an antigen, remains during this process. The role of the B-lymphocytes is to create matching antibodies based on the antigen. The role of the T-lymphocytes is to attack host cells that the pathogen has already invaded to prevent further infection or illness (CDC, 2024i; Ginglen & Doyle, 2023).

Vaccines contain a form of the disease-causing agent (i.e., a weakened or dead form, an inactivated version of the toxin, or a protein from the microbe's surface). Introducing the agent into the body allows the immune system to quickly recognize the antigen as foreign and develop antibodies and memory T-lymphocytes. The process enables the body to mount a robust and rapid immune response if exposed to the disease again. After an individual receives a vaccination, they may experience chills, fever, body aches, pain at the injection site, and fatigue secondary to the immune system’s response to the foreign material (i.e., the vaccine). It typically takes a few weeks to create the T-lymphocytes and B-lymphocytes following vaccination. Therefore, if an individual is exposed to the disease before the body achieves immunity, they can still become sick with the condition they were recently vaccinated against. When individuals are not vaccinated, the first exposure to an organism can be fatal before the immune system can mount a sufficient response (CDC, 2024i; Ginglen & Doyle, 2023; Hibberd, 2024; Justiz Vaillant & Grella, 2024).

Most vaccines induce active immunity by promoting the development of antibodies via a primary immune response. Then, if an individual is subsequently exposed to the pathogen, a secondary response occurs, increasing antibody formation (resulting in increased protection). The secondary response ideally protects individuals for life, but some vaccines require boosters to sustain protection. Passive immunization involves the administration of antibodies known as immune globulin, derived from pooled human serum or antitoxin harvested from immunized animals. Passive immunity is used for immunocompromised individuals who cannot mount an effective immune response. However, passive immunity is not commonly recommended for healthy adults and only offers short-term protection. Passive immunization is occasionally used for pregnant patients, international travelers, and health care workers (Ginglen & Doyle, 2023; Hibberd, 2024; Justiz Vaillant & Grella, 2024).

Types of Vaccines

There are many ways to create a vaccine. The most common vaccinations are live attenuated, inactivated, toxoid, subunit, mRNA, and conjugate. Live attenuated vaccines contain live viruses or bacteria that have been weakened to prevent an active infection in an individual with a healthy immune system. Since these vaccines contain a live version of the pathogen, they create an immune response and memory similar to naturally acquired immunity. Examples of live attenuated vaccines include MMR, rotavirus, and varicella. Since these vaccines contain live material, they are contraindicated in immunocompromised patients. Live attenuated vaccines offer long-lasting protection after two doses (CDC, 2024i; US Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2022).

Inactivated vaccines are also created to protect against bacteria and viruses, but the virus or bacteria is killed or inactivated during production. An example of this type of vaccine is the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). The process of developing immunity following the administration of an inactivated vaccine is different than live attenuated vaccines, so multiple (three or more) doses are typically required at set intervals (i.e., a series). The protection provided by these vaccines fades over time. These vaccines are safe for immunocompromised individuals (CDC, 2024i; HHS, 2022).

Toxoid vaccines are specifically designed to protect an individual against a bacterium that produces toxins once it enters the body. This type of vaccine creates an immune response targeted to the toxin instead of the whole pathogen. During the production of these vaccines, the toxin is weakened to the point that it cannot cause illness. The weakened form of the toxin is known as a toxoid. The toxoid vaccine allows the individual's immune system to learn how to combat the full-strength toxin. An example of a toxoid vaccine is the DTaP vaccine, which contains diphtheria and tetanus toxoids (CDC, 2024i; HHS, 2022).

The DTaP vaccine also contains a subunit vaccine for acellular pertussis. Subunit vaccines contain only essential pieces of the pathogen, resulting in a strong immune response targeted toward the key pieces of the pathogen. These vaccines can be administered to immunocompromised individuals because side effects following administration are less common. Subunit vaccines require booster shots to provide ongoing protection. The acellular pertussis vaccine contains inactivated pertussis toxin and one or more bacterial components. This vaccine was developed in the 1980s in response to a high rate of complications reported after administering the previously used whole-cell (inactivated) pertussis vaccine (CDC, 2024i; HHS, 2022).

Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines are a type of nucleic acid vaccine that works by teaching our cells how to make a protein that will trigger an immune response in the body. This immune response produces antibodies that protect the individual if the actual virus enters the body. mRNA vaccines are newly available to the public, specifically for the COVID-19 virus. Instead of using weakened or inactivated pathogens, the vaccine uses mRNA created in a laboratory. Once the mRNA vaccine enters the body, it uses the cells' machinery to produce a spike protein that is found on the pathogen. Once the spike protein is made, the cells break down and remove the mRNA, leaving the body as waste. The spike protein is displayed on the cells’ surface, triggering an immune response that recognizes the spike protein if it enters the body at some later point (CDC, 2024h; HHS, 2022).

The last type of vaccination is a conjugate vaccine. This type of vaccine protects against bacteria with a polysaccharide outer coating, which makes it more difficult for the immune system to recognize the pathogen. These vaccines connect or conjugate the target antigen’s polysaccharide coating to antigens that the immune system recognizes and has an effective response against. This helps the immune system develop the appropriate response to the target antigen. An example of a conjugate vaccine is the Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine (CDC, 2024i; HHS, 2022).

Adult and Child Immunization Schedules

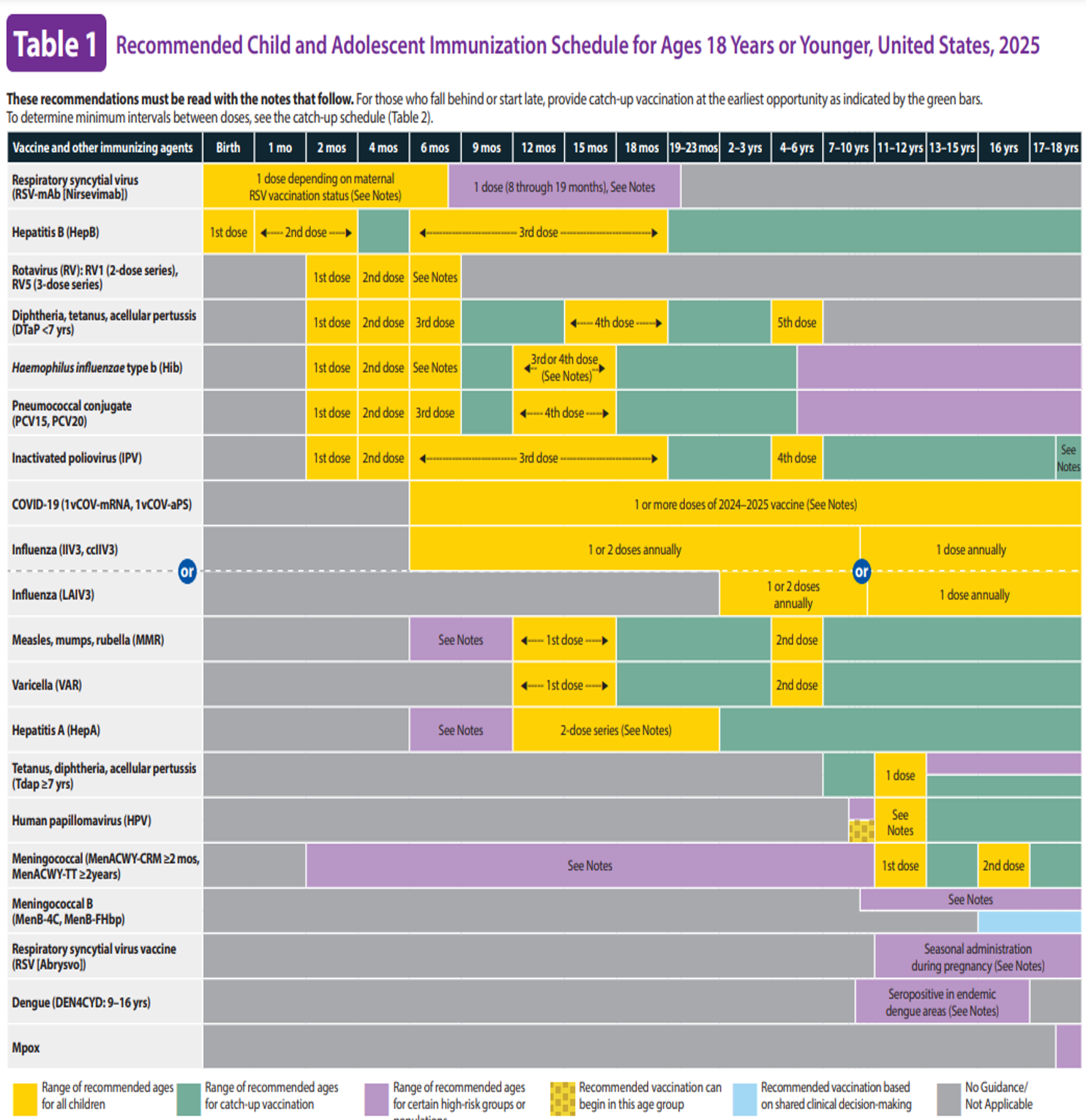

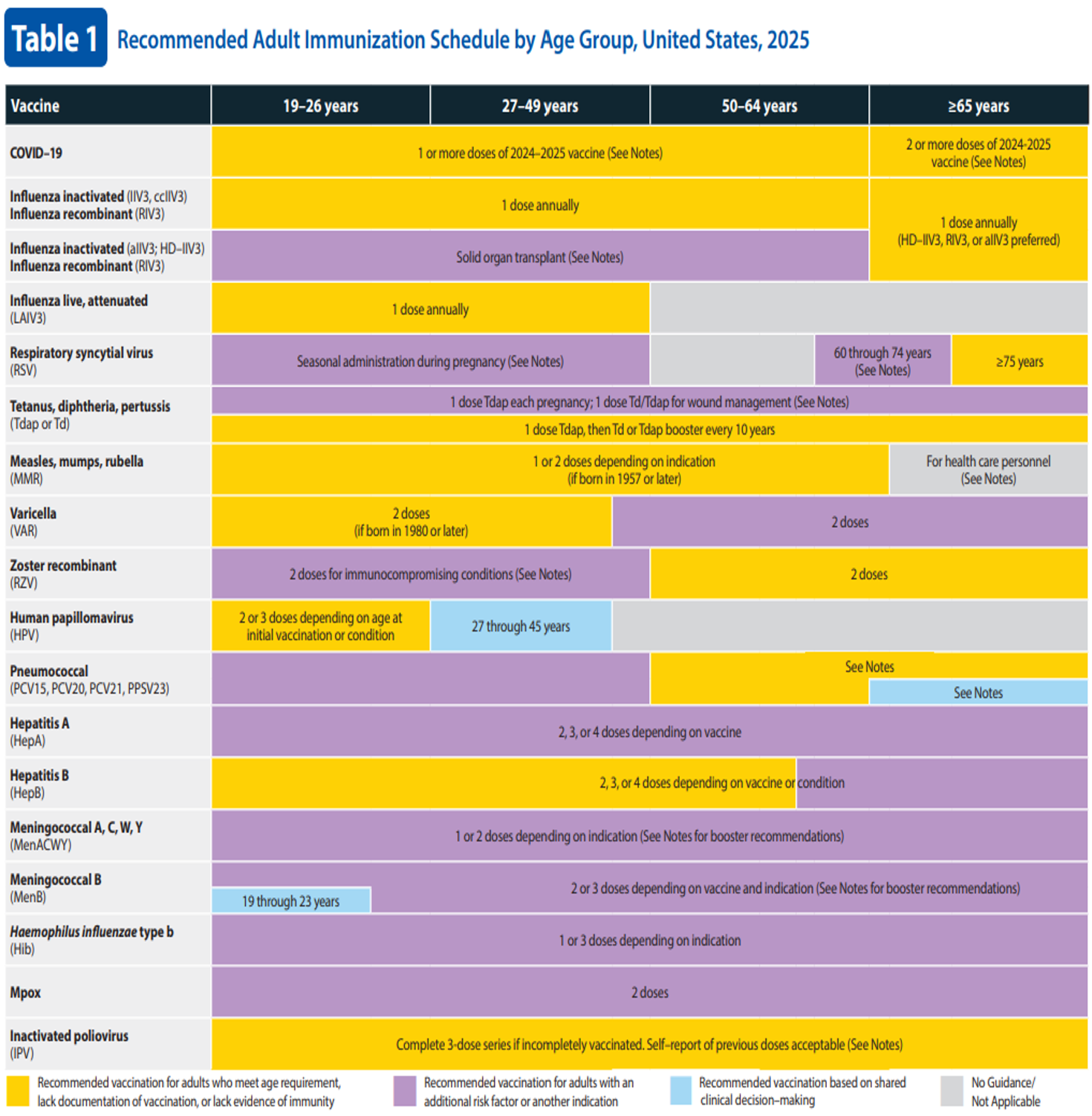

The CDC puts forth immunization recommendations and schedules in the United States based on the policies of the ACIP. The recommended immunization schedules in the United States for children (ages 18 years or younger) and adults (ages 19 years and older) can be found in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (CDC, 2024d, 2024f).

Figure 1

Recommended Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule for Ages 18 Years or Younger, United States, 2025

(CDC, 2024f)

Figure 2

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule by Age Group, United States, 2025

(CDC, 2024d)

Influenza Vaccine

Influenza or flu is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the orthomyxovirus family that can lead to serious illness, hospitalization, or death. Each season, the flu is slightly different, and it affects millions of people (averaging 8% of the US population), with hundreds of thousands needing hospitalization. Complications can arise from influenza infection, including bacterial pneumonia, ear and sinus infections, and exacerbations of chronic respiratory illnesses such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Receiving a yearly flu vaccine is the best way to prevent influenza infection and decrease the likelihood of hospitalization. Three different types of influenza are known to infect humans: A, B, and C. Type A influenza has subtypes determined by surface antigens hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 different H subtypes and 11 different N subtypes, with 8 H types and 6 N types being detected in humans. Type B influenza is classified into two lineages: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria. Children are most commonly infected with influenza B. Influenza C is rarely reported in human illness because many of the cases are subclinical. Influenza is transmitted from person to person via large respiratory droplets and has an incubation period of 1–4 days. The onset of symptoms may occur suddenly and include cough, sore throat, runny nose, fever, chills, headache, malaise, vomiting, and diarrhea (Hall, 2021; Kalaarikkal & Jaishankar, 2024).

The influenza vaccine is available in multiple forms: an inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV), recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV), or live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV). Some influenza vaccines are produced by growing the virus inside chicken eggs. Due to this production process, the vaccine may contain trace amounts of egg protein. Egg-free options include the cell-culture–based IIV (Flucelvax; for individuals 6 months and older) and the RIV4 (Flublok; for individuals 18 years and older). Individuals with an egg allergy are still able to receive any of the influenza vaccines approved for use in their age group; however, those who experience severe allergic reactions need to receive the vaccination in a health care setting under the supervision of an HCP who can recognize and manage a severe allergic reaction. Adverse effects following vaccination include injection site soreness and swelling, headache, fatigue, and muscle pain (CDC, 2023b, 2024p; Hibberd et al., 2024; Kalaarikkal & Jaishankar, 2024).

The CDC recommends the IIV annually for anyone over 6 months of age. It is administered intramuscularly and is available as a trivalent (containing three influenza virus strains) or quadrivalent vaccine (containing four influenza virus strains). For the 2024–2025 influenza season, trivalent vaccines (including one influenza A H1N1 virus, one influenza A H3N2 virus, and one influenza B Victoria lineage) will be used because the B/Yamagata virus has not been detected globally since 2020. Each type of influenza vaccine has a recommended age range. The minimum age for the IIV variations includes 6 months and older for IIV3 (inactivated influenza vaccine trivalent) and ccIIV3 (cell-cultured inactivated influenza vaccine trivalent), 2 years and older for LAIV3, and 18 years and older for RIV3. For children under the age of 8 receiving their first-ever influenza vaccination, two doses should be given at least four weeks apart. It is recommended that children are vaccinated as soon as the yearly vaccination is made available to ensure immunity before an influenza outbreak occurs in the individual's community. The highest numbers of influenza cases occur during February and March; therefore, vaccination is recommended even if flu season has already begun (CDC, 2024f, 2024g, 2024p).

For adults 19 and older, the standard dose IIV3 (Flarix, FluLaval, and Flozone) is a subunit vaccine given intramuscularly. Other available options for adults include ccIIV3 (Flucelvax), RIV (Flublok), and LAIV (FluMist), which is a quadrivalent nasal spray approved for use between 2 and 49 years old. LAIV should not be given to individuals with a history of severe allergic reactions to any vaccine component (excluding egg) or a previous dose of any influenza vaccine. In addition, it should not be given to individuals who are immunocompromised, have anatomic or functional asplenia, are pregnant, have cochlear implants, or have cranial cerebrospinal fluid/oropharyngeal communications. High-dose (HD-IIV3) and adjuvant (aIIV3) are available for adults over the age of 65 because they have an added ingredient to help the vaccine create a strong immune response. Adults aged 19 to 64 are recommended to have an annual influenza vaccine (IIV3, ccIIV3, RIV3). Adults 65 years and older are recommended to have an annual influenza vaccine (HD-IIV3, RIV3, or aIIV3). Solid organ transplant recipients aged 19 to 64 who are receiving immunosuppressive medication are recommended to have an annual influenza vaccine (HD-IIV3 or aIIV3; CDC, 2024d, 2024e; Hibberd et al., 2024).

The CDC recommends that all HCPs are vaccinated for influenza annually to help prevent the spread of the disease to patients, coworkers, and families. Some health care systems have started requiring employee vaccination or proof of vaccination off-site. Between March and April of 2024, the CDC conducted an opt-in internet survey of 2,750 US HCPs to estimate influenza vaccine coverage for the 2023–2024 flu season. They found that 75.4% of HCPs reported receiving the influenza vaccine, with the lowest rates found among assistants and aides, those working in long-term care (LTC) or home health settings, and those whose employers did not require or recommend the vaccine. Vaccine coverage was highest among pharmacists (93.9%), physicians (93%), and those who worked in hospital settings (89.1%; CDC, 2024k). Refer to the Nursing CE course Influenza: Signs, symptoms, treatment, and prevention for more information on influenza.

Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis

Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis are different diseases that can be prevented with one vaccination. Diphtheria is an infection of the nose and throat caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae that can lead to difficulty breathing, heart failure, paralysis, and even death. Tetanus is an infection caused by a bacterium toxin, Clostridium tetani, that affects the nervous system and can lead to lockjaw, difficulty breathing, and death. Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a respiratory infection caused by Bordetella pertussis, resulting in uncontrollable and sometimes violent coughing paroxysms, making breathing difficult. Pertussis is most serious in infants and young children and can lead to pneumonia, brain damage, and even death. The CDC recommends that everyone be vaccinated against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis. The diphtheria and tetanus portions of the vaccine contain a toxoid, and the pertussis portion is a subunit vaccine with acellular pertussis bacteria components and inactivated pertussis toxin (CDC, 2021d, 2022; Ogden et al., 2022).

For children, there are two vaccinations available for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis: DTaP (used to provide immunity) and tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap; used to boost immunity). DTaP is approved in the United States for use in children younger than 7. It is recommended that infants receive three doses of the DTaP vaccine at 2, 4, and 6 months old. After this initial series, children should receive a booster dose at 15–18 months and again at 4–6 years for five total doses. The Tdap vaccine contains smaller diphtheria toxoid and pertussis components and focuses on the tetanus toxoid. To boost immunity, all children between the ages of 11 and 12 should receive a dose of Tdap. The DTaP vaccine provides 98% protection against pertussis for the first year following vaccination, and approximately 71% coverage for the next five years. The DTaP and Tdap vaccinations effectively prevent tetanus and diphtheria for approximately 10 years following vaccine administration. The DTaP vaccine is contraindicated in children with a prior history of allergic reaction to the vaccine or one of its components, and those with a prior history of encephalopathy not attributable to another cause within seven days of a previous DTaP dose. Precaution is advised in those with a prior history of GBS, Arthus-type hypersensitivity reactions, progressive neurological disorders, or in those with a moderate to severe acute illness (CDC, 2022, 2024f, 2024g; Ogden et al., 2022).

Two vaccines are available for adults: Tdap (Adacel, Boostrix) and tetanus-diphtheria (Td, Tenivac, Tdvax). Adults who completed the primary series and received at least one dose of Tdap at 10 years or older should be given a Td or Tdap every 10 years. Adults who did not receive a Tdap booster as an adolescent can be given one dose as an adult, followed by a Td or Tdap booster vaccine every 10 years. For wound management in adults, HCPs should consider Tdap or Td administration. Tdap or Td should be administered for clean or minor wounds if it has been more than 10 years since the last Tdap or Td. For all other wounds, administer Tdap or Td if it has been more than five years since the previous Tdap or Td or if the vaccination status cannot be verified. Since 2012, this vaccine has been recommended during pregnancy to help protect the fetus and newborn, especially susceptible to pertussis infection, during the first eight weeks of life. The CDC recommends that Tdap be given between 27 and 36 weeks of gestation. The Td and Tdap vaccines are contraindicated in those with a history of a severe allergic reaction after a prior dose. The Tdap is also contraindicated in those with a prior history of encephalopathy not attributable to another cause within seven days of a previous DTaP, Td, or Tdap dose. Precaution is advised in those with a prior history of GBS, Arthus-type hypersensitivity reactions, progressive neurological disorders, or in those with a moderate to severe acute illness (CDC, 2021d, 2022, 2024d, 2024e; Ogden et al., 2022).

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR)

Measles (often referred to as rubeola) is a highly contagious virus transmitted via droplets when coughing or sneezing. A measles infection begins with a cough, runny nose, fever, and red eyes. As the disease progresses, small red spots appear on the skin, starting on the head and eventually spreading caudally (Gastanaduy et al., 2021). Mumps is a viral infection characterized by swollen parotid glands, fever, headache, and body aches, and can lead to viral meningitis (Marlow et al., 2021). Rubella (also German measles) is a mild viral infection in children that typically causes a fever, sore throat, and rash that originates on the face and spreads across the body. Rubella can be highly dangerous in pregnant patients, especially if contracted in the first trimester, potentially causing a miscarriage or severe congenital disabilities if the unborn child survives (Lanzieri et al., 2021). Internationally, the measles vaccination is available in 190 member states, with single-dose worldwide coverage of 83% and two-dose coverage of 74% worldwide. There were 107,500 deaths related to measles in 2023, mostly among unvaccinated or under-vaccinated children under the age of five. The mumps vaccine is currently only available in 124 member states worldwide, while the rubella vaccine is available in 175 member states with global coverage of 71% (WHO, 2024d, 2024f).

The vaccine used to prevent all three diseases is known as the MMR vaccine, which is named after the three diseases. There are two vaccinations available in the United States: M-M-R II and ProQuad. M-M-R II is an MMR vaccine and ProQuad also contains varicella (MMRV). Both vaccines contain live, attenuated measles, mumps, and rubella virus. It is recommended that children receive two doses, the first at 12–15 months old and the second at 4–6 years old. For international travel, infants 6 through 11 months should receive one dose of the MMR vaccine, and those over 12 months should receive two doses of a measles-containing vaccine 28 days apart. If a child receives a dose of the MMR vaccine before 12 months due to international travel or a community-wide outbreak of measles, mumps, or rubella, two doses should still be administered at 12–15 months and 4–6 years. The MMR vaccine is very effective at preventing all three diseases. After receiving both doses, the MMR is 97% effective at preventing measles and 88% effective at preventing mumps. Individuals who receive both doses are considered immune for life against measles and rubella. Immunity to mumps does decrease over time (CDC, 2021b, 2021c, 2024f, 2024g).

The routine MMR vaccination for adults (19–64 years) with no evidence of immunity (i.e., born after 1957) is one dose. For HCPs, patients with HIV, and students in postsecondary institutions or international travelers, a two-dose series for four weeks apart is recommended. MMR and MMRV are contraindicated in patients who have had an allergic reaction to previous doses of the vaccine or any component of the vaccine, are severely immunocompromised (as it is a live attenuated vaccine), or have a family or personal history of immunodeficiency. Specifically, the MMR is contraindicated in pregnant patients, individuals with HIV with a CD4 count of fewer than 200 cells/mm3, and those with severe immunocompromising conditions. In addition, vaccination should not occur for one month following treatment with systemic high-dose corticosteroids for over 14 days and 3–11 months after receiving antibody-containing blood products. Adverse reactions following the administration of MMR include fever greater than 103° F, rash, arthralgia, febrile seizures, and anaphylactic reaction (Bailey et al., 2024; CDC, 2021c, 2024d, 2024e; Marlow et al., 2021).

Varicella

The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a member of the herpesvirus family. Primary infection with VZV causes a highly contagious disease known as varicella or chicken pox. VZV enters the body via the respiratory tract and conjunctiva. Once infected, the disease causes an itchy, blistering rash that first appears on the face and trunk and spreads to the extremities. The rash rapidly progresses from macules to papules to vesicular lesions. Symptoms tend to be mild in children, and recovery usually results in lifetime immunity; however, VZV can remain in the body as a latent infection. VZV used to be a widespread childhood illness until the varicella vaccination became available in the United States in 1995. Before widespread vaccine use, 4 million people contracted chicken pox annually, with approximately 13,000 of those requiring hospitalization and over 150 deaths (Kota & Grella, 2023; Lopez et al., 2021).

There are two formulations of the chicken pox vaccine. VAR (Varivax) only contains the chicken pox vaccine, while MMRV (ProQuad) combines varicella with MMR. The MMRV is only approved for children ages 1 to 12. For any individual who has not had chicken pox or received a vaccination, the CDC recommends two doses of the varicella vaccine. The first dose is recommended at 12–15 months and the second at 4–6 years old. When administering catch-up doses, the administrations should be spaced at least three months in children ages 7-13 and four weeks in individuals over 13. Varicella vaccination is contraindicated in any individual with a history of anaphylactic reaction to a previous dose of the vaccine or any component of the vaccine (including gelatin and neomycin); those diagnosed with leukemia, lymphoma, malignant neoplasm of the bone marrow or lymphatic system; patients with primary or acquired immunodeficiency, including HIV; those who are receiving immunosuppressant or high-dose corticosteroid medications; patients who are pregnant; or those suffering from a moderate to severe illness. For 14 days after vaccination, individuals should not receive blood products unless the need for blood outweighs immune protection against VZV. Typically, administering salicylates is contraindicated for six weeks following varicella vaccination due to the risk of Reye syndrome; however, vaccination is possible in children diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis or another disorder requiring administration of salicylates, under close monitoring by an HCP (CDC, 2021e, 2024f, 2024g). After administration, the most common adverse effects include fever greater than 102° F, rash, injection site tenderness, and edema. Administration of the MMRV has an increased incidence of fever-induced seizures compared to administering the MMR and varicella vaccines separately (Lopez et al., 2021).

The VAR vaccine is recommended for adults (anyone 13 and older) with no evidence of immunity to varicella (i.e., born after 1980 or no documented evidence of varicella-containing vaccine). The VAR vaccine is administered in a two-dose series 4–8 weeks apart if the person did not previously receive a varicella-containing vaccine. If the person previously received one dose of a varicella-containing vaccine, a second dose is administered at least four weeks after the first. A similar administration schedule should be used for HCPs. For persons with HIV, two doses of the VAR vaccination may be considered three months apart (CDC, 2021e, 2024d, 2024e).

Herpes Zoster Recombinant (RZV)

Herpes zoster vaccines are exclusively for use in adults to prevent shingles. Zostavax (ZVL) is a live vaccine previously approved for adults aged 60 or above that is no longer available in the United States (as of November 2020). Shingrix (RZV) is a recombinant vaccine approved as a two-dose series that should be given 2–6 months apart at 50 years and older for immunocompetent adults. RZV was approved for use in 2017. It reduces the risk of shingles or postherpetic neuralgia by 90%. It is also safe for immunocompromised patients. RZV is recommended for use in patients over 18 who are (or will be) immunosuppressed due to disease or therapy. The CDC recommends two doses of the RZV to prevent shingles in immunocompromised adults 19 and older. The first and second doses should be given 2–6 months apart. If ZVL was previously given, RZV should be given at least two months (eight weeks) after ZVL. If more than six months have passed since the initial dose, the second dose should be given as soon as possible. The CDC does not recommend restarting the series. The RZV vaccine is contraindicated in those with a prior history of allergic reaction to the vaccine or one of its components. Precaution is advised in those with a moderate to severe acute illness or current herpes zoster infection (CDC, 2024d, 2024e, 2024o).

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. Although most individuals infected with HPV are asymptomatic, the virus can cause reproductive and oral cancers later in life. The HPV vaccine prevents genital warts and many types of cancer, including cervical, oropharynx, anal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancer. The cost of treating HPV-associated disease is $9 billion, making widespread vaccination a cost-effective preventative measure (Clay et al., 2023). Before HPV vaccine approval, there were 14 million new cases of HPV per year in the United States. Since the HPV vaccination was first approved in 2006, infection with the types of HPV that cause cancers and genital warts has decreased by 86% in teenage girls and 71% in young adult patients ages 20–24, and long-term protection has continued (Meites et al., 2021).

The only vaccine currently available against HPV (Gardasil-9) is a recombinant vaccine that protects against nine different HPV types. The CDC recommends that the first dose of HPV vaccine be given between 11–12 years old, with the second dose given 6–12 months later; however, the series can start in individuals as young as 9 years old. Only two doses are required if both doses are given before an individual's 15th birthday. If the series is not finished before an individual turns 15, three doses of the vaccine are recommended through 26 years old. The second dose should be given at 1–2 months, and the third should be given at 6 months. Contraindications to vaccine administration include anaphylaxis to a previous dose of the HPV vaccine or any of its components, including yeast, since Gardasil-9 is produced in baker's yeast. The vaccine should not be given during pregnancy. Following vaccination, common adverse effects include local reactions (pain, tenderness, swelling), fever above 100° F, malaise, nausea, and dizziness. Syncope is also common following vaccination; therefore, the patient should be seated or lying down during administration until 15 minutes after administration. In addition, the HPV vaccine can be given to adults 27 to 45 years old based on shared clinical decision-making. After the initial dose, the vaccine should be repeated at 1–2 months and 6 months. The series is not restarted if the vaccination schedule is interrupted. For persons with HIV or other immunocompromising conditions, a three-dose series is recommended regardless of age at initial vaccination (CDC, 2021a, 2024e, 2024f). For more information on HPV, refer to the Nursing CE course on Human Papillomavirus.

Pneumococcal (PCV13, PCV15, PCV20, PCV21, PPSV23)

According to the WHO (2024d), the pneumococcal vaccine was introduced in 159 member states by the end of 2023, and global third dose coverage is 65%. Similar to other vaccines, coverage with the pneumococcal vaccine varies by region, with the European region having 86% coverage and the Western Pacific region only having 26% coverage. PCV13 is a conjugate vaccine against 13 different pneumococcal bacteria that can cause meningitis, pneumonia, febrile bacteremia, otitis media, sinusitis, or bronchitis in children. PCV13 was approved for use in 2010 and replaced the PCV7 vaccine, which was introduced in 2000 and protected against seven types of pneumococcal bacteria. It was estimated that in the first three years following its introduction, the use of PCV13 prevented over 30,000 cases of pneumococcal disease and over 3,000 deaths (Gierke et al., 2021). Both PCV15 and PCV20 were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adults over 18 in 2021. In 2024, the FDA approved 21-valent PCV (PCV21) for use in individuals over 18. The FDA approved the PCV15 for use in children in 2022 and PCV20 in 2023, replacing the use of PCV13. A related vaccine, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), is a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine introduced in 1983 (CDC, 2024a).

The CDC recommends that children receive PCV15 or PCV20 at 2, 4, 6, and 12–15 months old to be fully vaccinated. For healthy children aged 2–4 with an incomplete pneumococcal vaccination series, one dose of PCV15 or PCV20 is recommended. Side effects after administration include pain and swelling at the injection site, decreased appetite, lethargy, headache, irritability, and fever. PCV15 or PCV20 should not be administered to anyone with a history of severe allergic reaction to a previous dose of the vaccine or any component, including diphtheria toxoid. HCPs must be cautious administering PCV15 or PCV20 to any individual experiencing a moderate to severe acute illness. Although not contraindicated, studies have shown that simultaneous administration of PCV15 or PCV20 and inactivated influenza vaccine increased the risk of febrile seizures in young children (CDC, 2024f, 2024g; Gierke et al., 2021). Children diagnosed with a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak; who have diabetes, chronic heart, liver, kidney, or lung disease; or those who have a cochlear implant are at a higher risk for infection with invasive pneumococcal disease and require special approaches to pneumococcal vaccination. For children with these conditions, the CDC recommends the following:

- Children aged 2–5 with an incomplete PCV series:

- Received three doses of PCV: administer one dose of PCV (at least eight weeks after the most recent PCV dose)

- Received less than three doses of PCV: administer two doses of PCV (eight weeks apart)

- Children aged 2–5 with a complete PCV series but no PPSV23:

- Previously received at least one dose of PCV20: no further PCV or PPSV23 is needed

- Not previously received PCV20: administer one dose of PCV20 or one dose of PPSV23 (at least eight weeks after the most recent PCV dose)

- Children aged 6–18 who have not received any dose of PCV13, PCV15, or PCV20:

- Administer one dose of PCV15 or PCV20; if PCV15 is used and they have not received PPSV23, then administer one dose of PPSV23 eight weeks after PCV15

- Children aged 6–18 who received PCV before the age of 6 but did not receive PPSV23:

- Previously received at least one dose of PCV20: no further PCV or PPSV23 is needed

- Not previously received PCV20: administer one dose of PCV20 or one dose of PPSV23 (at least eight weeks after the most recent PCV dose)

- Children aged 6–18 who received PCV13 only at or after the age of 6:

- Administer one dose of PCV20 or one dose of PPSV23 (at least eight weeks after the most recent PCV dose)

- Children aged 6–18 who received one dose of PCV13 and one dose of PPSV23 at or after the age of 6:

- No further PCV or PPSV23 is needed (CDC, 2024f, 2024g)

The PCV vaccine is recommended for adults 50 years and older and those 19–49 years of age with certain immunocompromising conditions that place them at increased risk (i.e., congenital or acquired immunodeficiency; chronic renal, heart, liver, or lung disease; lymphoma; generalized malignancy; solid organ transplant; anatomical or functional asplenia; alcoholism; cigarette smoking; cochlear implant; CSF leak; diabetes; HIV infection; solid organ transplant; and sickle cell disease or other hemoglobinopathies; CDC, 2024d, 2024e). The CDC recommends the following for routine pneumococcal vaccination:

- Adults ages 50 and older

- Not previously received a dose of PCV13, PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21, or those whose vaccination history is unknown: administer one dose of PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21; if PCV15 is used, administer one dose of PPSV23 at least one year after the PCV15 dose

- Previously received only PCV7: administer one dose of PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21; if PCV15 is used, administer one dose of PPSV23 at least one year after the PCV15 dose

- Previously received only PCV13: administer one dose of PCV20 or PCV21 at least one year after the last dose of PCV13

- Previously received only PPSV23: administer one dose of PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21 at least one year after the last dose of PPSV23 dose

- Previously received both PCV13 and PPSV23, but no PPSV23 was received after the age of 65: administer one dose of PCV20 or PCV21 at least five years after the last pneumococcal vaccine

- Previously received both PCV13 and PPSV23, and PPSV23 was received after the age of 65: one dose of PCV20 or PCV21 can be administered five years after the last pneumococcal vaccine based on shared decision-making (CDC, 2024d, 2024e)

- Adults aged 19–49 with underlying medical conditions described above:

- Not previously received a PCV13, PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21 or whose vaccination history is unknown: administer one dose of PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21; if PCV15 is used, administer one dose of PPSV23 at least one year after the PCV15 dose

- Previously received only PCV7: administer one dose of PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21; if PCV15 is used, administer one dose of PPSV23 at least one year after the PCV15 dose

- Previously received only PCV13: administer one dose of PCV20 or PCV21 at least one year after the last dose of PCV13

- Previously received only PPSV23: administer one dose of PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21 at least one year after the last dose of PPSV23 dose

- Previously received PCV13 and one dose of PPSV23: administer one dose of PCV20 or PCV21 at least five years after the last pneumococcal vaccine

- Previously received PCV20 or PCV21: no additional pneumococcal vaccine dose is recommended (CDC, 2024d, 2024e)

PPSV23 is contraindicated in those with a severe allergy, and precaution should be taken in those with moderate to severe acute illness with or without a fever. PCV15, PCV20, or PCV21 are contraindicated in those with a severe allergic reaction to a previous dose or a diphtheria-toxoid–containing vaccine. Precaution should be taken in those with moderate to severe acute illness with or without a fever (CDC, 2024d, 2024e). For more information on pneumonia, refer to the Nursing CE course Pneumonia.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is a contagious virus that leads to liver infection. Transmission occurs via the fecal-oral route through close person-to-person contact, sexual contact, or ingestion of contaminated food or drink. Symptoms of a hepatitis A infection include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the appearance of jaundice due to liver involvement. These symptoms usually appear two to six weeks after exposure and can last up to six months but do not lead to a chronic illness, and most individuals do not have long-lasting effects of the virus. Although rare, hepatitis A can cause liver failure. Children under 6 are often asymptomatic but can transmit the disease to older children and adults who may become symptomatic (Bhandari et al., 2023; CDC, 2025b).

Currently, there is no treatment available that is designed explicitly for hepatitis A; therefore, the best means of protection is prevention through vaccination. There are two single-antigen hepatitis A (HepA) vaccines, Havrix and Vaqta, that are approved for children. These vaccines contain an inactivated form of hepatitis A. HepA vaccination is a two-dose series recommended for children ages 12–23 months old, with a second dose six months later. Side effects following vaccination are mild and include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, and injection site soreness. Hepatitis A infections dropped by 95% from 1995 to 2011 after the initiation of the vaccine. Since 2016, there has been a spike throughout multiple states caused by person-to-person transmission and infection. The number of hepatitis A infections nearly doubled between 2015 and 2022, with 49% of cases occurring in people aged 30–49 and 56% of cases occurring among non-Hispanic White people (CDC, 2024f, 2024g, 2025b; Foster et al., 2021).

HepA is recommended in a two- or three-dose series for adults with additional risk factors or another indication. For adults at risk for hepatitis A or those who are not at risk but want protection, a two-dose series (6–12 months apart) of HepA or a three-dose series (at 0, 1, and 6-month intervals) of HepA-HepB (Twinrix) can be given. Individuals considered to be at risk for hepatitis A include those with chronic liver disease, HIV infection, persons experiencing homelessness, those who work with hepatitis A in a lab, travel to countries with high rates of hepatitis A, men who have sex with men, persons who use injectable or noninjectable illicit drugs, pregnant patients, and persons who work in settings where exposure can occur (such as health care). If a person has a functional immune system and receives both doses of any available vaccine, they are considered to have life-long immunity against hepatitis A. The vaccine is contraindicated in people who have had a severe allergic reaction after a previous dose or to a vaccine component, including neomycin. Precaution should be taken in those with moderate to severe acute illness with or without a fever (CDC, 2024d, 2024e, 2025b). For more information on hepatitis, refer to the Nursing CE course Hepatitis.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is a highly contagious disease that affects the liver. Although infected children are often asymptomatic or experience mild symptoms, they can become carriers and infect an adult, who may then have more severe symptoms. Hepatitis B is transmitted through contact with infected blood or other bodily fluids and can cause lethargy, fever, decreased appetite, joint and muscle pain, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Hepatitis B can occur as an acute infection or develop into a chronic illness, with about half of infected people being unaware that they are infected. It usually takes three to four months after exposure before symptoms appear (CDC, 2025c). Hepatitis B (HepB) is a vaccination against the hepatitis B virus that is currently available in 190 member states with global coverage for three doses of the HepB vaccine at 83%. In addition, 177 member states introduced one dose of the HepB vaccine in the first 24 hours of life (WHO, 2024d). The HepB vaccine was approved for use in the US in 1981 (Vanderslott et al., 2024).

The HepB vaccine is created using the hepatitis B surface (or 's') antigen (HBsAg). The CDC recommends that children receive the three-dose HepB vaccination at birth (if birth weight is greater than 2,000 grams), 1–2 months old, and 6–18 months old. There are multiple HepB formulations available for children. Recombivax HB and Enerix-B are single-antigen formulations (they only contain material specific to hepatitis B) and can be given as early as birth to initiate the vaccine series. It is recommended that infants receive the HepB vaccine at birth regardless of the infection status of the mother. Pediarix is a combination vaccine that contains hepatitis B, DTaP, and IPV. Pediarix is not approved for use in children under 6 weeks or over 7 years old. For infants whose mother is HBsAg positive or if the mother's HBsAg status is unknown, administration of the hepatitis B immune globin (HBIG) should occur within 12 hours of birth. The HepB vaccine is contraindicated in individuals who have had an allergic reaction to a previously administered HepB vaccine or have an allergy to yeast. HepB vaccination can occur concurrently with other vaccinations; however, a different site and syringe should be used. If previous vaccine administration cannot be verified, there are no contraindications to administering extra doses or restarting the entire series. A healthy individual with a functioning immune system should remain resistant to hepatitis B for approximately 30 years (CDC, 2024f, 2024g, 2025c).

The CDC recommends two, three, or four doses for adults aged 19–59 years. The two-dose series (Heplisav-B) should be given at least four weeks apart. The three-dose series (Engerix-B, PreHevbrio, Recombivax, or HepA-HepB [Twinrix]) should given at 0, 1, and 6-month intervals. The four-dose series (HepA-HepB [Twinrix]) accelerated schedule consists of 3 doses at 0, 7, and 21–30 days, followed by a booster at 12 months. Adults 60 and over should receive the HepB vaccine if they have specific risk factors for HepB. In addition, routine vaccination can be administered to individuals not considered at risk for hepatitis B but who want protection. Risk factors for hepatitis B include chronic liver disease, HIV infection, and sexual exposure risk (e.g., sex partners with hepatitis B, sexually active persons not in a monogamous relationship, men having sex with men, persons seeking evaluation and treatment for a sexually transmitted infection [STI]). Other risk factors include current or recent injection drug use, percutaneous or mucosal risk for exposure to blood, pregnancy, travel to countries with high hepatitis B rates, and incarceration (CDC, 2024d, 2024e, 2025c).

Meningitis

Meningitis is an infection of the meninges surrounding the brain that can be viral, bacterial, or fungal. Bacterial meningitis can be caused by Neisseria meningitidis or meningococcus. Bacterial meningitis can be severe, with a 10–20% mortality rate even with optimal treatment. It can also lead to loss of limbs, deafness, or brain damage. There is an increased risk of transmission in close living quarters, such as dormitories and barracks, as it is transmitted via saliva and other respiratory secretions. There are five main serogroups of meningococcus: A, B, C, W, and Y. Since the CDC began recommending the MenACWY vaccine for adolescents in 2005, the infection rate by the meningococcal serogroups included in the vaccine has decreased by more than 90% (CDC, 2023a; Daraghma & Sapra, 2023).

There are currently three different types of meningococcal vaccines in the United States, with each type helping to protect against different serogroups of meningococcal disease. MenACWY vaccines protect against serogroups A, C, W, and Y. MenB vaccines protect against serogroup B. MenABCWY vaccines protect against all five serotypes. The CDC recommends that the first dose of MenACWY be administered at age 11–12, with a booster dose at 16. If the first dose is administered after 16, a booster dose is not needed in healthy individuals. The MenACWY vaccine protects individuals from four different types of bacteria that cause meningococcal infections and can be administered simultaneously with MenB vaccines. Adverse effects following administration of MenACWY include irritability, malaise, headache, and injection site pain. Contraindications to vaccination include a history of anaphylactic response to a previous dose of any vaccine component. MenB is recommended in individuals over 10 diagnosed with complement deficiency, HIV, functional or anatomic asplenia, or are taking a complement inhibitor. For those individuals at risk, a three-dose primary series of a MenB vaccine is recommended at 0, 1–2, and 6-month intervals. Regular boosters are given one year after the series completion and every two to three years after that (CDC, 2024f, 2024g, 2024l; Mbaeyi et al., 2021).

The CDC recommends one or two doses of the MenACWY for adults, depending on the indication. The MenACWY two-dose series is recommended for persons with anatomical or functional asplenia or HIV infection. A single dose of MenACWY is recommended for persons traveling in countries with high rates of meningococcal disease or first-year college students living in residential housing (if not vaccinated at 16 years). The CDC recommends two or three doses of the MenB vaccine, depending on the vaccine and indication. MenB is recommended for persons with anatomical or functional asplenia, and microbiologists are routinely exposed to Neisseria meningitidis. In addition, persons 16–23 years at average risk may elect to receive the MenB vaccine based on a shared clinical decision between patient and provider. All meningitis vaccines are contraindicated in those with a prior history of severe allergic reaction to the vaccine or one of its components; precaution should be exercised before administration to those patients with a moderate to severe acute illness. Those with a prior allergic reaction to any diphtheria toxoid vaccine should not be given the MenACWY-D or CRM. Those with a prior allergic reaction to any tetanus toxoid vaccine should not be given the MenACWY-TT. Precaution should be exercised prior to administering the MenB vaccine to a patient who is pregnant or who has a latex sensitivity (MenB-4C only; CDC, 2024d, 2024e, 2024l).

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B (Hib)

Hib is a bacterium that affects children under 5 years old, causing severe illness or death. It is spread through direct person-to-person contact, coughing, and sneezing. Examples of infections caused by Hib include bronchitis, pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis. Long-term consequences can include brain damage, intellectual disability, blindness, and deafness. At one time, Hib was the primary cause of bacterial meningitis infections among children under 5 in the United States, leading to the death of over 1,000 children each year. The Hib vaccine is a polysaccharide conjugate vaccine that is highly effective in eliciting immunity to Hib bacteria. The vaccine is currently available in 193 member states with an estimated coverage of 77% worldwide. However, there is a significant variation in coverage, with the European region having 94% coverage and the Western Pacific region having only 33% coverage (National Institute of Health, n.d.; WHO, 2024d).

The CDC recommends that all children receive a Hib vaccination with either a four-dose series at 2, 4, and 6 months old (if using Hiberix, ActHIB, Pentacel, or Vaxelis) and a booster dose between 12–15 months old or a three-dose series (PedvaxHIB) given at 2 months, 4 months, and a booster at 12–15 months. This booster dose between 12–15 months old is necessary to provide complete protection against Hib and must be given at least 8 weeks after the previous dose of the Hib vaccine. Vaxelis should not be used as this booster dose. The Hib vaccine can be administered in infants as young as 6 weeks old. Hib vaccination is available as a stand-alone vaccine or in combination with other vaccinations. Hib vaccination is contraindicated in any patient with a history of severe allergic reaction to a previous Hib vaccination or any vaccine component and infants less than 6 weeks old. In patients experiencing moderate to severe illness with or without a fever, the benefits of vaccination must be weighed against the risks of vaccination. Hiberix, ActHib, and PedvaxHIB should not be given to patients with a history of severe dry natural latex allergy. The Hib vaccine is immunogenic in patients diagnosed with sickle-cell disease, leukemia, HIV, or a history of a splenectomy (CDC, 2024f, 2024g).

The CDC recommends one or three doses for adults depending on the risk factors or the indication. If not previously vaccinated, one dose is recommended for patients with anatomical or functional asplenia, including sickle cell disease. In addition, one dose is recommended at least 14 days before surgery if undergoing elective splenectomy. Finally, a three-dose series is recommended for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) regardless of vaccination history. The three-dose series should be given four weeks apart, beginning 6 to 12 months after transplantation. As mentioned above, Hib is contraindicated in any adult with a prior severe allergic reaction to the vaccine or one of its components, and precaution should be taken before administering it to a patient with moderate to severe acute illness (CDC, 2024d, 2024e).

Polio

At one time, polio was the most feared disease in the United States, causing disability in over 35,000 people per year in the country. Parents were afraid to send their children out of the house, and government-imposed quarantines were implemented to prevent the spread of the poliovirus. Unlike other viruses, the rate of infection increased over the summer months. In 1955, the first vaccine designed against polio was introduced. The length of immunity is unknown; however, the poliovirus has been eliminated from the United States. There have not been any cases of poliovirus that originated in the United States since 1979 (Estivariz et al., 2021). However, there is still a risk of exposure for those traveling internationally to areas where the poliovirus is still a threat, such as Pakistan and Afghanistan (WHO, n.d.-a).

The CDC recommends administering four doses of IPV at 2, 4, 6–18 months, and 4–6 years old. If a child received IPV in a combination vaccination, they might require a fifth dose, which is safe and recommended. Once three doses are administered, the protection rate against polio is 99–100%, and at four doses, a child is considered fully vaccinated. There is an accelerated vaccination schedule for children traveling outside of the United States to an area where the risk of contracting polio is increased. If the accelerated schedule cannot be completed prior to departure, the series should be continued upon arrival to the destination or immediately upon return to the United States. If a child is vaccinated outside of the United States and cannot provide reliable vaccination documentation, they should be vaccinated following the CDC vaccination schedule (CDC, 2024f, 2024g).

Adults who are known or suspected to be unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated should have a three-dose series of IPV. IPV is contraindicated in individuals who have a history of allergic reaction to a previous dose of IPV vaccine and any components of the vaccine, including streptomycin, polymyxin B, and neomycin, or are suffering from a moderate to severe illness. Common adverse effects include localized pain and erythema, fever, irritability or fussiness, fatigue, and crying. Adverse effects following IPV administration tend to be mild with a short duration. When not in use, the IPV vaccine needs to be refrigerated at 36–46° F (2–8° C; CDC, 2024d, 2024e; Estivariz et al., 2021).

Rotavirus

Rotavirus causes a viral illness characterized by severe diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain in infants and young children. Rotavirus is transmitted via the stool of an infected individual. Rotavirus can survive on the surface of inanimate objects for several days and is difficult to prevent through good hand hygiene and surface cleaning, leading to a quick spread through families, hospitals, and childcare centers. The effects of rotavirus can last for 3–8 days, and children may not tolerate oral intake during active infection. Rotavirus infection can be critical, especially in infants and young children, due to diarrhea, fever, and vomiting coupled with a lack of oral intake. This combination can cause severe dehydration, which can be life-threatening and may require hospitalization for fluid resuscitation via intravenous fluid replacement. Despite the availability of a vaccine for rotavirus, more than 200,00 people die annually worldwide (LeClair & McConnell, 2023).

It is recommended that children are vaccinated against rotavirus to prevent infection and serious complications. The rotavirus vaccine was approved for use in the United States in 2006. Currently, two rotavirus vaccines are approved for use: RotaTeq and Rotarix. Both vaccines contain live attenuated forms of rotavirus and are given orally. The primary difference is that RotaTeq requires three doses, and Rotarix only requires two doses to be considered fully vaccinated. Administration of RotaTeq should occur at 2, 4, and 6 months of age. Administration of Rotarix should occur at 2 and 4 months of age. The first dose of either vaccine should be administered before 15 weeks of age, and the entire series should be administered before 8 months old. If the first dose is administered to an infant older than 15 weeks, the remaining doses should be administered according to the recommended schedule. Children over 8 months should not receive the rotavirus vaccine even if the series has not been completed (CDC, 2024f, 2024g; Vanderslott et al., 2024).

Both vaccines typically cause only mild adverse effects such as irritability, mild diarrhea, and vomiting. In rare cases, intussusception may occur, requiring hospitalization and possibly surgery. If intussusception were to occur, it usually occurs within one week of administration. The rotavirus vaccine is contraindicated in infants with a history of allergic reaction to a previous dose of the vaccine or any component of the vaccine, intussusception, or severe combined immunodeficiency. Infants that are mildly ill may still receive the rotavirus vaccine, but any moderately or severely ill infant should wait until they recover to receive the vaccine. This includes any infant suffering from moderate to severe diarrhea or vomiting (CDC, 2024f, 2024g).

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a common respiratory virus that infects the nose, throat, and lungs, causing mild cold symptoms. RSV spreads in the fall and winter months and can be difficult to distinguish from other illnesses that are prevalent during this time (i.e., influenza, COVID-19). In healthy adults and children, RSV does not usually cause severe illness. However, infants younger than 6 months and older adults can develop severe RSV, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia, requiring hospitalization. The CDC recommends two ways to protect infants from severe RSV: a maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo) given during pregnancy or an RSV antibody given to infants after birth. Infants born between October and March to mothers who did not receive the RSV vaccine, who received the vaccine less than 14 days before delivery, or whose vaccine status is unknown should receive one dose of nirsevimab (Beyfortus) within 1 week of birth (ideally before discharge). Infants born April through September born to those who did not receive the RSV vaccine, who received the vaccine less than 14 days before delivery, or whose vaccination status is unknown should receive one dose of nirsevimab (Beyfortus) shortly before the start of RSV season. Nirsevimab (Beyfortus) can be administered to children 8–19 months old with certain conditions, including chronic lung disease of prematurity requiring medical support at any time during the 6 months before RSV season, severe immunocompromise, or cystic fibrosis. In these situations, one dose of nirsevimab (Beyfortus) should be administered shortly before the start of the second RSV season. Nirsevimab (Beyfortus) is contraindicated in anyone who has had a severe allergic reaction to a previous dose or vaccine component. Caution should also be taken for infants and children with moderate or severe acute illness, with or without a fever (CDC, 2024b, 2024f, 2024g).

For adults ages 75 and older, the CDC recommends one dose of the RSV vaccine (Arexvy, Abrysvo, or mResvia). At this time, the RSV vaccine is recommended as a one-time administration. As more data is collected, these new vaccine recommendations may be adjusted. Adults aged 60–74 who are at increased risk for RSV can also get one dose of the RSV vaccine. Risk factors include chronic heart, lung, liver, hematologic, or renal disease, diabetes, neurologic or neuromuscular conditions causing impaired airway clearance or respiratory muscle weakness, BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, moderate to severe immunocompromise, or residence in a long-term care facility (CDC, 2024b, 2024d, 2024e).

COVID-19

COVID-19 is a respiratory illness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, fever, and body aches. COVID-19 spreads when an infected person breathes out droplets that contain the virus, and these spread to another person. Much like other respiratory illnesses, certain people are at higher risk for developing severe disease from COVID-19. Risk factors include older age, weakened immune system, and underlying health conditions. The CDC recommends routine vaccination for COVID-19 starting at 6 months of age. For unvaccinated children aged 6 months to 4 years, the current recommendation is two doses of 2024–2025 Moderna, with the second dose occurring 4–8 weeks after the initial dose. The other vaccine option is three doses of the 2024–2025 Pfizer-BioNTech at 0, 3–8, and 8 weeks after the second dose. For children aged 6 months to 4 years who had an incomplete vaccination series or a complete vaccination series before the 2024–2025 vaccine, one dose of either the 2024–2025 Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is recommended (8 weeks after the more recent dose). All vaccines given to children 6 months to 4 years of age should be from the same manufacturer. Children aged 5–11 who are unvaccinated or vaccinated before the 2024–2025 vaccine should receive either one dose of the 2024–2025 Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines. Children aged 12–18 who are unvaccinated should receive either one dose of the 2024–-2025 Moderna or Pfizer vaccines or two doses of the 2024–2025 Novavax, with the second dose 3-8 weeks from the initial dose. For children aged 12–18 who were previously vaccinated, one dose of the 2024–2025 Moderna, Pfizer, or Novavax should be given (Cascella et al., 2023; CDC, 2024f, 2024g).

Adults aged 19–64 years who are unvaccinated should receive either one dose of the 2024–2025 Moderna or Pfizer vaccines or two doses of the 2024–2025 Novavax, with the second dose 3–8 weeks from the initial dose. For those who were previously vaccinated, one dose of the 2024–2025 Moderna, Pfizer, or Novavax should be given 8 weeks after the most recent dose. Adults over 65 should follow the same recommendations as adults 19–64, but require an additional two doses of either the 2024–2025 Moderna, Pfizer, or Novavax vaccines 6 months later, with 2 months in between these doses. Contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine include a severe allergic reaction to a previous dose or a component of a COVID-19 vaccine. Precautions should be taken for people who had a previous non-severe allergy to the COVID-19 vaccine, who developed myocarditis or pericarditis within 3 weeks of a COVID-19 vaccine, who have multisystem inflammatory syndrome, or moderate to severe acute illness (CDC, 2024d, 2024e).

Pregnancy Considerations

The CDC and a panel of experts have recommended influenza, Tdap, RSV, and COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy. A recent systematic review was conducted to evaluate the associations between the influenza vaccine during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes and maternal non-obstetric serious adverse events. The researchers found that the seasonal influenza vaccine during pregnancy was not associated with adverse birth outcomes (preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, and infant born small for gestational age) or maternal non-obstetric serious adverse events (Wolfe et al., 2023). The CDC recommends IIV or RIV for pregnant patients, as live vaccinations (i.e., LAIV) are not recommended in pregnancy. One dose of the Tdap vaccine is recommended in pregnancy, preferably in weeks 27 to 36. RSV is a common cause of severe respiratory illness in infants. The CDC recommends the RSV vaccine (Abrysvo) during weeks 32–36 weeks, specifically between September and January. The COVID-19 vaccine is safe to administer during pregnancy, and getting vaccinated during pregnancy can protect babies younger than 6 months of age. The CDC recommends that the HPV vaccine not be given until after pregnancy. The HepA and Hep B vaccines can be administered during pregnancy if the person is at risk of infection, although Heplisav-B is contraindicated in pregnancy. The MMR vaccine is a live vaccine and is, therefore, contraindicated during pregnancy. Similarly, the VAR vaccine is contraindicated during pregnancy. Both can be administered after delivery before discharge. The CDC recommends delaying the administration of meningitis and RXV vaccines until after pregnancy unless the benefits outweigh the potential risks (CDC, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e).

Global Vaccination Trends

Some diseases are found more frequently outside of the United States and represent a significant risk to worldwide health, such as dengue fever, malaria, and cholera. Dengue fever (or dengue) is a mosquito-borne illness caused by the dengue virus. Up to 20% of the severe form of dengue is lethal. It is mainly found in very rainy areas/seasons of Bangladesh and India, but roughly 50% of the world is at risk, with the highest number of cases recorded in 2023. According to the WHO, there were over 6.5 million cases affecting 80 countries, resulting in 7,300 dengue-related deaths. The disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries, with the Americas, Southeast Asia, and Western Pacific regions accounting for 70% of the disease burden. The vaccine developed for dengue by Sanofi is a live attenuated vaccine called CYD-TDV or Dengvaxia. It was released in 2015 and is the only vaccine available in the United States. Dengvaxia is recommended to prevent dengue in children aged 9–16 living in endemic areas. While the vaccine is helpful, it is far from a perfect solution. The vaccine improves immunity in patients with a prior history of dengue infection (seropositive), and it increases the risk of severe dengue and hospitalizations in seronegative people. For that reason, people must have a confirmed history of dengue infection or should be screened with an antibody titer prior to vaccination. For this reason, most prevention programs currently focus on reducing transmission via the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Sanofi is going to stop making Dengvaxia because of the lack of demand from the global market. Two other dengue vaccines have been approved, but they are not currently available in the United States (CDC, 2025a; WHO, 2024c).

Malaria is a parasitic infection transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. Five parasite species cause malaria, with P. falciparum and P. vivax posing the greatest risk. Worldwide, there were 263 million malaria cases in 2023, with 597,000 associated deaths across 83 countries. The African region accounted for 94% of malaria cases and 95% of malaria deaths. In addition, children under 5 years old accounted for 76% of all malaria deaths in that region. RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix) is an injectable vaccine that has been shown to significantly reduce malaria and severe malaria among children. Therefore, since October 2021, the WHO has recommended the general use of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine for children living in moderate to high P. falciparum transmission regions. In 2023, a second malaria vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, was found to be safe and effective. Malaria vaccines are now included in routine childhood immunization programs across Africa (WHO, 2024e).