About this course:

The purpose of this activity is to review and highlight the evidence-based care of patients diagnosed with substance use disorder to facilitate the provision of optimal care.

Course preview

Substance Abuse and Addiction (for APRNs)

The purpose of this activity is to review and highlight the evidence-based care of patients diagnosed with substance use disorder to facilitate the provision of optimal care.

Upon completion of this module, learners will be able to:

- define the terms and epidemiology associated with substance use disorder and addiction

- review the pathophysiology, risk factors, and protective factors related to substance use disorder and addiction

- explain the intended effects and signs and symptoms of intoxication and withdrawal for the most common substances abused

- highlight the screening tools and diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder and addiction

- evaluate the most effective and evidence-based treatment options available for substance use disorder and addiction, as well as pending research

Various definitions relate to the effects of utilizing particular substances, whether used illicitly or as prescribed by a healthcare provider (HCP). Tolerance is the gradual need for an increased dose of a particular medication or substance to obtain a similar effect over time. The development of tolerance varies significantly from individual to individual and from medication to medication and is a result of the brain's ability to adapt to its environment physically. This phenomenon is not limited to pain medication or illicit drugs but is also seen in other specialties and circumstances. Physical dependence is the physiological adaptation to a medication that develops with consistent and regular use and is a component of addiction. The medicine becomes necessary for normal homeostasis and functioning. This phenomenon typically correlates with opposing withdrawal symptoms if that medication is no longer used. Some substances have specific symptoms of withdrawal. Opioid withdrawal often presents as rhinitis, abdominal cramping, nausea, restlessness, and agitation. Addiction is a combination of physical dependence and compulsive drug-seeking behaviors despite significant negative repercussions. Misuse of prescription drugs is ingesting or utilizing these medications in a manner, at a dose, or by an individual other than prescribed. This includes taking someone else's medication or taking pain medication to induce feelings of euphoria instead of pain relief (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021; Hudspeth, 2016a; Ignatavicius et al., 2021).

The medical terms substance abuse and substance dependence have been replaced in recent years with the term substance use disorder (SUD). This is the term used in the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). This may refer to an individual addicted to nicotine, alcohol, prescription medications, or illicit drugs. Another phenomenon, pseudoaddiction, involves a patient becoming intensely fearful of being in pain. This is common in postoperative patients and usually manifests as clock-watching, asking to be awoken to receive pain medication, and hypervigilance with documenting and monitoring pain medication administration. Pseudoaddiction usually resolves with effective pain management treatments and the resolution of painful stimuli; for postoperative patients, this is the healing of the surgical site. Psychological dependence occurs when medication ingestion becomes associated with alleviating discomforts, such as pain, anxiety, and depression. The presence of that drug then becomes a calming and reassuring presence in the patient’s life, similar to a comfort or security object (CDC, 2021; Hudspeth, 2016a; Ignatavicius et al., 2021).

Epidemiology

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2022) conducts the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) regarding substance use in the US, which was last performed in 2021. This survey includes self-reported data on over 69,850 noninstitutionalized Americans over 12 and is conducted across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. It does not include data on long-term facility residents, incarcerated individuals, or homeless individuals not currently residing in a homeless shelter. The 2021 version of the NSDUH utilized multimode data collection, and respondents could participate in person or via the web. Due to this difference in data collection, the results are not comparable to data collected in previous years (SAMHSA, 2022).

The NSDUH estimates that in 2021, 61.6 million (22%) individuals used tobacco or nicotine vaping. Of those, 43.6 million smoked cigarettes (27 million, or 61.9%, daily), 10.3 smoked cigars, 7.3 million used smokeless tobacco, 1.8 million used pipe tobacco, and 13.2 used nicotine-only vape. In 2021, approximately 3 of every 5 adolescents aged 12 to 17 who used nicotine products in the last month vaped but did not use tobacco products. An estimated 133.1 million Americans over 12 used alcohol in the previous month (1.8 million between the ages of 12 to 17). Of those, 60 million (45.1%) reported binge drinking (drinking five or more drinks at a time for males and four or more drinks at a time for females), and 16.3 million reported heavy drinking (binge drinking on five or more days out of 30). Asian individuals were the least likely (10.7%) to report binge drinking in the past month compared to individuals of other ethnic backgrounds. Of those surveyed, 61.2 million (21.9%) reported illicit drug use in the past year (i.e., marijuana, cocaine/crack, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamines, and prescription stimulants, tranquilizers, sedatives, and analgesics used inappropriately). Marijuana was the most used illicit drug, with 52.5 million (18.7%) reporting use in the last year. The second most used illicit drug was prescription pain relievers. Approximately 8.7 million (3.1%) Americans reported misusing prescription analgesics in the past year. When asked why prescription analgesics were misused, 64.3% reported misuse to relieve physical pain, 10.7% to get high, 7.3% to alleviate tension or relax, and 4.6% to help with sleep. Of those who utilized analgesics inappropriately, 44.9% reported that they obtained the medication from a relative or friend in some way, and 43.2% reported obtaining the medication using a prescription or by stealing directly from their HCP (SAMHSA, 2022). The estimated usage in the last month of cocaine; prescription sedatives, tranquilizers, or other central nervous system (CNS) depressants; prescription stimulants; hallucinogens; methamphetamine (meth); and inhalants, as well as the number of individuals who utilized a substance within the last year, are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1

Substance Users Over the Age of 12 in the Last Month and Year

Group | Last 30 Days | Last Year |

No substance use | 233.6 million | |

Alcohol use | 133.1 million | 29.5 million* |

Use of marijuana | 36.4 million | |

Misuse of prescription opioids | 2.4 million | 8.7 million |

Use of cocaine | 1.8 million | 4.8 million |

Misuse of prescription sedatives/tranquilizers/hypnotics | 1.4 million | 4.9 million |

Misuse of prescription stimulants | 1.1 million | 3.7 million |

Use of hallucinogens | 2.2 million | 7.4 million |

Use of methamphetamine (meth) | 1.6 million | 2.5 million |

Use of inhalants | 830,000 | 2.2 million |

Use of heroin | 589,000 | 1.1 million |

* alcohol use disorder reported in respondents in the past year (SAMHSA, 2022)

Many addiction experts suspect a public perception that prescription opioids and other CNS depressants are safer than illicit drugs because they are regulated, prescribed by a provider, and used therapeutically. This perception, in combination with the ease of access to CNS depressants, is responsible for the relatively large number of individuals who abuse prescription opiates in comparison to the small number of individuals who abuse heroin. This belief is supported by the NSDUH results, which indicate that 92.3% of respondents associated weekly heroin use with overall significant risk, 83.7% with weekly cocaine use, 68.4% with having more than 4 or 5 alcoholic drinks per day, and 69.2% with daily tobacco smoking (equivalent to at least one pack of cigarettes per day). Only 26.5% of respondents associated significant risk with weekly marijuana use (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2020; SAMHSA, 2022).

SAMHSA (2022) utilizes the diagnostic criteria for SUD from the 5th edition of the DSM to estimate SUD rates. In 2021, 46.3 million individuals over 12 (equivalent to 16.5% of the population) had a SUD in the previous year. Of those, 29.5 million had an alcohol use disorder (AUD), and 24 million had a drug use disorder. Of the 29.5 million individuals with AUD, 7.3 million had a concurrent SUD. Following alcohol, the most common substances associated with SUD include marijuana (16.3 million) and prescription opioids (5.0 million). Adding a small percentage of users based on treatment in the past year for SUD, SAMHSA estimated that 43.7 million (15.6%) Americans needed treatment for SUD in 2021, despite only 4.1 million (1.5%) receiving said treatment. Of those who did not receive treatment, 39.5 million (96.8%) did not feel that treatment was required. Among those who did perceive a need, 36.7% of respondents cited not being ready to stop using, 24.9% cited a lack of insurance coverage or financial resources to afford treatment, 17.9% did not know where to go to receive treatment, 15.8% were unable to find a facility that offered the type of treatment they were seeking, 15% felt they could treat themselves without intervention, and 14.7% were concerned about possible negative impacts on their employment (SAMHSA, 2022).

According to NSDUH estimates, in 2021, 19.4 million (7.6%) adults and over 935,000 (3.7%) adolescents ages 12 to 17 had SUD in combination with another mental illness, such as depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and others. Adolescents aged 12 to 17 who have experienced a major depressive episode (MDE) within the last year are more likely to abuse illicit substances (27.7% versus 10.7%), binge drink (6.7% versus 3.1%), and use tobacco products or vape (14.3% versus 4.7%). Adults with mental illness are also more likely to use illicit drugs (39.7% versus 17.7%), misuse opioids (10.3% versus 7.7%), binge drink alcohol (27.9% versus 21.9%), and use tobacco products or vape (37.3% versus 20.9%; SAMHSA, 2022).

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS, 2022), SUDs are a significant public health concern. The annual cost of illicit substance misuse is approximately $193 billion, and the cost of alcohol use is $249 billion in the US. The costs attributed to SUD include lost productivity, judicial and penal services, treatment of infants born with dependence, emergency room visits, overdoses, and treatment of the comorbid conditions accompanying SUD (e.g., sepsis, pancreatitis, liver failure). There are also costs to the treatment of SUD. For example, treatment with methadone (Dolophine) and daily outpatient encounters with various support services cost about $126 per week or $6,552 annually. Outpatient buprenorphine (Sublocade) treatment with twice-weekly encounters and support services costs $115 per week or $5,980 annually (HHS, 2022; NIDA, 2021b).

Pathophysiology

While the root cause of addiction is still not entirely understood, research points to environmental and genetic factors. According to NIDA (2019), half of the risk for addiction is composed of genetic factors. These genetic variations are not found on a single gene, as in Down's syndrome (trisomy 21), but in smaller alterations in numerous genes. Up to 30% of cannabis users meet the criteria for SUD, and researchers have identified a locus on chromosome 8 controlling the expression of gene CHRN2, which is associated with SUD in cannabis users when levels of expression are lower than average (NIDA, 2019a).

Addiction is considered a brain disorder due to the exacerbating factors that lead to drug abuse and the changes in brain chemistry due to drug use. However, it is important to note that addiction is not possible if an individual is never exposed to a particular substance, and some individuals never experience addiction despite substance use. Repeated exposure to a specific drug over time changes how the brain processes, primarily how it processes pain and pleasure; the threshold varies between individuals and substances. This may be related to structural changes in the neurons and neurotransmitters, which typically persist beyond the immediate effects of the drug and lead to the chronic nature of SUD (NIDA, 2020a).

Long-term effects of substance use include decreased educational attainment, unemployment or underemployment, unstable housing, strained personal relationships, and criminal justice involvement. Aside from the financial, social, personal, professional, and legal consequences that may accompany substance use, the health consequences are short and long-term. Short-term health consequences include changes in appetite, wakefulness, heart rate, blood pressure, or mood; acute myocardial infarction; stroke; psychosis; and overdose/death. The long-term effects are varied and extensive but can include lung disease, heart disease, dental problems, cancer, mental illness, HIV/AIDs, hepatitis, cellulitis, endocarditis, and impulsivity and poor decision-making leading to an increased risk of trauma, violence, or injury (NIDA, 2020a).

Risk and Protective Factors

There are several risk factors for the development of SUD. As previously mentioned, half of the risk is genetic, as evidenced by a family history of addiction (NIDA, 2019a). Most risks occur early in life, even during gestational development. The following factors increase a person’s risk of SUD:

- maternal smoking and alcohol use

- low parental education level

- having a “difficult temperament” during infancy

- insecure attachment to a parent(s)

- uncontrolled aggression as a toddler

- lack of school readiness skills

- poor emotional regulation

- extended screentime exposure

- easy access to substances/availability

- lack of classroom structure as a child

- chronic stress (i.e., family poverty, serious parental illness, child maltreatment)

- parental or family substance abuse

- a personal history of mental illness, especially early mental illness (e.g., anxiety, depression, ADHD, conduct disorder)

- academic failure

- social/emotional difficulties

- family rejection of sexual or gender identification

- history of physical or sexual trauma/abuse

- low academic achievement

- lack of connection with school and associated activities

- peer pressure or associating with delinquent or substance-abusing peers

- the use of certain high-risk substances (stimulants, cocaine, opioids; CDC, 2022b; Nawi et al., 2021; NIDA, 2016)

Studies have also identified many protective factors against SUD, including:

- good maternal nutrition

- a birth weight that is within normal limits

- a solid parent-child bond

- improving behavior control during preschool years

- school readiness skills

- increased intelligence

- an easy temperament (flexible, cheerful, optimistic mood)

- parenting that is warm, consistent, and age-appropriate

- parents who regularly listen to and communicate with their children

- praise for accomplishments

- parents who provide a good example and consistent rules and routines

- opportunities for regular social interaction/after-school programs and exercise

- strong religious beliefs (CDC, 2022b; Nawi et al., 2021; NIDA, 2016)

Screening and Diagnosis

APRNs should perform screening for the risks of SUD before prescribing an opioid using a validated screening tool, such as the following (Ogilvie et al., 2020):

- The Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) is an 11-part survey used by prescribers before initiating opioid therapy; it evaluates the patient’s medical, psychosocial, and family history associated with substance abuse.

- One of the most established surveys used to predict future misuse of opioids is the pain medication questionnaire (PMQ); this validated survey consists of 26 questions.

The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain - Revised (SOAPP-R) and the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) can be used to screen current opioid users. The SOAPP-R is a 24-item questionnaire for chronic pain patients to assess their ability to self-manage their treatment. The COMM is a 17-item questionnaire that evaluates signs and symptoms of abuse, psychiatric disorders, evidence of willful dishonesty, provider visitation patterns, and medication noncompliance (Ogilvie et al., 2020).

More generic screening tools can be used for multiple substances, including the following (NIDA, 2023b):

- Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription medication, and other Substance Use Tool (TAPS) is a self-administered tool that combines screening and, if positive, a brief assessment for adult patients.

- NIDA Drug Use Screening Tool: Quick Screen (NMASSIST) is a clinician-administered tool for adult patients. The American Psychiatric Association’s adapted version, NIDA-modified ASSIST, is a self-administered version to screen for drug or alcohol misuse in adult or adolescent patients.

- CAGE Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID) is a brief questionnaire screening for drug and alcohol misuse based on the original CAGE tool (utilized for alcohol only).

- Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) and Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and other Drugs (BSTAD) are self-administered tools designed to screen adolescents for drug and alcohol misuse.

- The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), both the self-administered and clinician-administered versions, screens for alcohol use disorder (AUD) in adult patients.

Being aware of the signs and symptoms of SUD and active substance use will allow APRNs to identify patients, coworkers, or even family/friends who may be struggling with addiction (American Addiction Centers, 2023). The signs and symptoms of addiction may include:

- increased agitation or irritability

- personality changes

- lack of energy or motivation

- changes in behavior (sudden insistence on privacy, being secretive, different friends)

- doing immoral/illegal/unethical things to obtain the substance

- conjunctival irritation (red or bloodshot eyes)

- dilated or constricted pupils

- abrupt changes in weight

- sudden change in appearance and hygiene (lack of interest in clothes, grooming)

- slurred speech, tremors, impaired coordination

- a need to use the substance regularly

- an obsession with protecting or maintaining a steady supply of the substance

- financial issues, spending large amounts of money to obtain the substance without regard for the availability of those resources, requests for money without an explanation, reports of missing cash or valuable personal items from those around the user

- dropping grades (adolescents) or poor performance at work (adults)

- engaging in high-risk behavior while under the influence of the substance, such as driving (American Addiction Centers, 2023; NIDA, 2021c)

Some red flags can signal that a patient may be misusing or diverting their prescribed medications. These include rapid increases in the amount of medication needed, frequent/unscheduled refill requests, repeated dramatic stories about prescriptions or medication being lost or stolen, multiple visits with multiple providers or pharmacies, resistance to nonopioid and nonpharmacological treatments, or frequent after-hours calls to the on-call prescriber or trips to the emergency department (ED) resulting in prescriptions. Prescribers should be aware of the common pitfall of assuming a well-liked or well-known patient is at a lower risk for abuse/misuse. Patients who repeatedly delay needed or planned surgeries and opt instead to treat an otherwise correctable condition with medications should be monitored closely. Data support the prescribing or offering of naloxone (Narcan), a potential overdose reversal agent, to high-risk patients exhibiting disturbing signs or symptoms of drug misuse that the prescriber deems aberrant. For these patients, careful consideration should be made regarding referral to a pain management or addiction specialist. If not, documentation of why a referral was not made must be thorough (Hudspeth, 2016b).

The diagnosis of SUD is clinical and based primarily on a thorough patient history. The DSM-5-TR lists 11 criteria for the diagnosis of SUD. Mild SUD is diagnosed when a patient meets 2-3 criteria, moderate SUD is diagnosed when 4-5 are met, and severe SUD is diagnosed when 6 or more are met. The criteria include four broad categories: lack of self-control (1-4), social impairment (5-7), personal risk (8 and 9), and pharmacological criteria (10 and 11). According to the DSM-5-TR criteria, SUD is a destructive repetition or habit of ingesting/administering an intoxicating substance that causes substantial anguish or drastically affects the patient’s ability to function professionally, socially, or otherwise (APA, 2022). These effects are evidenced by two or more of the conditions listed within a year:

- a persistent ingestion/administration of the substance for a longer time and at a higher dose or amount than planned

- ineffective attempts to reduce the use of the substance or a wish to do so but not being able to

- a considerable investment of time related to the substance, such as procuring it, ingesting/administering it, or recuperating from the consequences of its use

- an intense need or impulse to use the substance that eclipses other thoughts

- a persistent ingestion/administration of the substance, interfering with significant responsibilities and commitments (i.e., academic, professional, or familial)

- a persistent ingestion/administration of the substance despite repeated relational challenges (i.e., with friends and family members) related to its use

- a decrease in attendance or participation in significant events at work, at home, or with friends/family due to the use of the substance

- a persistent ingestion/administration of the substance in environments where it is unsafe

- a persistent ingestion/administration of the substance despite awareness of a significant challenge directly related to the substance use

- the development of tolerance, which is a gradual reduction in the physical impact/effect of a given substance when administered at a consistent dose or amount, requiring an increase in dose or amount to achieve the prior effect

- the development of withdrawal as evidenced by the signs and symptoms of withdrawal syndrome for that particular substance or the use of the substance to prevent these symptoms (APA, 2022)

The disorder may be considered in early (3 or more months) or sustained (12 or more months) remission when all these symptoms have resolved, except for an intense need or impulse to use the substance. This may also be established in a controlled environment if the patient currently lacks access to the substance (APA, 2022).

TAPS can be used as an assessment tool for adults whose screening is positive, as well as NMASSIST and Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). CRAFFT or the Alcohol screening and brief intervention for youth: A practitioner’s guide should be used to assess adolescents whose screening is positive for alcohol use (NIDA, 2023b).

Laboratory testing may be helpful. An elevated blood alcohol concentration may indicate acute intoxication and help assess tolerance to alcohol, and high (> 20 units) carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) or high-normal (> 35 units) gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is found in at least 70% of heavy drinkers. CDT and GGT levels return to normal within days to weeks of abstaining from alcohol. A serum or urine toxicology screen would indicate recent or current usage of various substances (APA, 2022).

Common Substances of Abuse

For this activity, we will focus on 8 of the 10 substances that the APA (2022) includes in their definition for SUD: opioids; sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics; stimulants; hallucinogens; tobacco, cannabis, and other inhalants. While caffeine is included in the DSM-5-TR, and serious adverse effects are possible (including insomnia, diuresis, and cardiac arrhythmia) with its use, they are rare. The substances contained in the DSM-5-TR's Other category are anabolic steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), nitrous oxide, antihistamines, betel nuts (areca nut), kava, cathinone (bath salts), and others. While some of these substances may have severe adverse effects, their prevalence in the US is likely significantly lower than those mentioned earlier, albeit based on minimal data (APA, 2022).

CNS Depressants: Alcohol, Opioids, Sedatives, Hypnotics, and Anxiolytics

The intended effects of CNS depressants vary somewhat. Alcohol is used recreationally with no intended medicinal effects. Opioids are designed to relieve pain. Most sedatives, anxiolytics, and hypnotics are intended to produce a sense of calm and relaxation or induce sleep. Opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics require an order from an HCP with prescribing privileges (NIDA, 2020b).

Prescription CNS depressants are indicated for use to induce sleep and relieve anxiety. Others may be manufactured and sold illicitly, such as gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB, typically homemade) and flunitrazepam (Rohypnol or "roofie"), a benzodiazepine (BZD) that is not approved for use in the US. Both are considered club drugs or "date rape" drugs, as they are often mixed with alcohol and used in sexual assault cases (Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA], 2020).

All CNS depressants can cause symptoms such as drowsiness/sedation, ataxia (lack of coordination), mood changes (e.g., depression), dysarthria (slurred speech due to muscle weakness), difficulty concentrating, poor memory, decreased inhibition, dizziness/falls, tachypnea, hypotension, nystagmus (involuntary eye movements), and confusion (Mayo Clinic, 2022).

Alcohol

AUD affects millions of Americans, costing $249 billion and taking at least 140,000 lives annually (CDC, 2022a). Slightly more than half of the respondents to the 2021 NSDUH reported some alcohol use in the last month. The survey found that 21.5% or approximately 60 million alcohol users reported binge drinking, defined as five or more drinks for men and four or more for women on at least one day in the past month. Roughly 5.8% (16.3 million individuals) of all alcohol users report heavy drinking, defined as binge drinking on at least five occasions in the past month. Heavy and binge drinking were reported most often in respondents between 18 and 25. Reports of alcohol use in the last month in the 12- to 17-year-old cohort have remained below 10% since 2015 and were 7.0% in 2021. Unfortunately, roughly half (3.8%) of the adolescents who reported alcohol use also attested to binge drinking. In addition to the symptoms mentioned earlier for all CNS depressants, alcohol intoxication can cause an unsteady gait, inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior, mood lability, impaired judgment, impaired social/occupational functioning, and stupor or coma. Repeated heavy drinking can cause chronic health problems, including gastritis, stomach or duodenal ulcers, liver cirrhosis, pancreatitis, low-grade hypertension, cardiomyopathies, increased triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, peripheral neuropathy leading to muscle weakness, paresthesia, and decreased peripheral sensation, cognitive deficits, memory impairment, degenerative changes in the cerebellum, vitamin B deficiencies, and an increased risk of suicide. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is a rare alcohol-induced CNS complication causing a severely impaired ability to encode new memory (APA, 2022; SAMHSA, 2022).

Withdrawal symptoms related to AUD typically present 4-12 hours after the reduction of intake, peak during the second day, and improve by the fourth or fifth day. Common symptoms include anxiety, headache (HA), depression, fatigue, irritability, mood swings, nightmares, and dysfunctional thinking. Less common withdrawal symptoms include autonomic hyperactivity (i.e., sweating, tachycardia with pulse above 100 bpm, dilated pupils), hand tremors, insomnia, poor appetite, and nausea and vomiting. Delirium tremens (DT), a severe form of alcohol withdrawal, can present with transient hallucinations or illusions, fever, psychomotor agitation, confusion, and seizures. The associated sleep disturbances, anxiety, and autonomic dysfunction may persist at lower intensities for months. In severe cases, alcohol withdrawal can be life-threatening, but symptoms are severe in only about 10% of cases, and seizures are seen in under 3% of cases (APA, 2022; MedlinePlus, 2021).

Alcohol use is incredibly risky during pregnancy; however, 10% of pregnant women between 18 and 44 report alcohol use in the last month. Fifty percent of nonpregnant women report alcohol use in the previous month, even though most women are unaware that they are pregnant for at least the first 4-6 weeks of their pregnancy. Exposure in utero to alcohol can lead to the development of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), which includes several biological, psychological, and physiological variants. This may include fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), congenital disabilities, and neurodevelopment and neurobehavioral disorders. They are all associated with significant morbidity and even mortality. Consequences of maternal alcohol use may include low birth weight, poor coordination, hyperactivity, impulsivity, inattentiveness, poor memory, learning and intellectual disabilities, speech and language delays, fine or gross motor delays, vision and hearing problems, and cardiac, renal, or skeletal malformations. These infants are more likely to become adults who are unemployed, incarcerated, or victims of violence later in life (Albrecht et al., 2019).

Universal assessment of all women of reproductive age via screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) may help identify those most at risk sooner to reduce the prevalence and improve the identification of FASD. Experts advocate for this screening to be completed as part of each patient’s annual wellness exam using a validated tool such as AUDIT by the World Health Organization. A score of 8 or higher on this scale indicates risk potential and warrants further assessment. The AUDIT-C is a condensed version with just three questions, asking about how often the patient consumes alcohol, how many alcoholic drinks they typically consume daily, and how often they have six or more alcoholic beverages on one occasion. A score of 3 or higher on this scale indicates a potential for AUD in women. After delivery, alcohol metabolites can be detected using an in-hospital fatty acid ethyl esters analysis of the meconium fluid (Albrecht et al., 2019).

Opioids

As many as 100 million Americans are estimated to suffer from chronic pain. Opioids are a group of controlled-substance analgesics that are commonly prescribed for moderate to severe pain control. Opioids bind to mu-opioid receptors (agonists) diffusely throughout the CNS. By attaching to a receptor in the CNS, they reduce or block the pain signal to the brain, thereby altering pain perception and response to pain. Opioids can also affect receptors in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract, so beyond their clinical uses for pain management, they are occasionally used to treat diarrhea and coughing. Opioids are classified as agonists, partial agonists, and mixed agonist-antagonists. Opioid antagonists may be used to counteract the adverse effects of opioids (Berger & O'Neill, 2022; NIDA, 2020b).

Opioid agonists produce a maximum biological effect between receptor binding and response (Berger & O'Neill, 2022). Opioids vary in the ratio of their analgesic potency and their potential for respiratory depression. According to HHS (2019), the most common opioid agonists prescribed for moderate or severe pain include:

- Hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lortab, Norco): found only in combination products, usually combined with acetaminophen; may be oral tablet formulation or liquid cough syrup

- Oxycodone (Roxicodone, Oxycontin): available as an immediate-release (IR) or extended-release (ER) formula, fast onset, available in oral tablet or solution form

- Morphine sulfate (Roxanol, MS Contin): available as IR or ER, as well as parenteral and oral formulations

- Oxymorphone (Opana, Opana ER): available as an IR or ER formula, long half-life

- Hydromorphone (Dilaudid, Exalgo ER): derivative of morphine but with a faster onset; available as an oral tablet, liquid, suppository, and parenteral formulations; available as an IR or ER formula (HHS, 2019)

They are classified into the following categories: naturally occurring alkaloids (derived from the opium poppy plant), synthetic (human-made), and semi-synthetic forms. These and other common types of opioid agonists are listed according to each category in Table 2.

Table 2

Opioid Agonists

Alkaloid | Synthetic | Semi-Synthetic |

Morphine (Roxanol, MS Contin) | Fentanyl (Duragesic) | Oxycodone (Roxicodone) |

Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | Methadone (Dolophine) | |

Oxymorphone (Opana) | Meperidine (Demerol) | |

Hydrocodone (Vicodin) | Levorphanol (Levo-Dromoran) | |

Codeine (Tylenol #3) |

(Berger & O'Neill, 2022)

Fentanyl (Duragesic) is a highly lipid-soluble opioid that can be administered through various parenteral routes and is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine sulfate (Roxanol, MS Contin). Similarly, heroin is a naturally derived product of morphine that is not approved for medicinal use within the US. Methadone (Dolophine) is a long-acting opioid important in neuropathic pain. Its prolonged plasma half-life allows for dosing once every 8 hours. However, prescribers must provide evidence of appropriate education to manage this drug. The half-life of methadone (Dolophine) is significantly longer than morphine (8 to 59 hours), is considerably cheaper than other medications, and is widely dispensed in SUD clinics as a component of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid-dependent patients. Since it is long-acting, it can delay the opioid withdrawal symptoms that patients experience when taking short-acting opioids. Therefore, it allows time for detoxification (Hudspeth, 2016b). Opioid prescribers are encouraged to consult and follow the CDC’s Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain for strategies proven to limit the risk of opioid misuse (NIDA, 2020b).

Partial opioid agonists have a submaximal response between receptor binding and response. They cause less conformational change and receptor activation than full agonists. Low doses provide similar effects to full agonists, but the analgesic activity plateaus when the amounts are increased. In other words, they have a ceiling effect. The continued dosing of these medications often leads to increased adverse effects without providing additional pain relief. Examples of partial agonists include tramadol (Ultram) and buprenorphine (Sublocade). Tramadol (Ultra) is a synthetic analog of codeine with a low affinity for opioid receptors commonly used to treat moderate to severe pain. It has a dual mechanism of action and a lower abuse potential than other opioids. Adverse effects include dizziness, vertigo, nausea, constipation, and headaches (Berger & O'Neill, 2022). Buprenorphine (Sublocade) is a semi-synthetic partial agonist used in MAT to treat opioid use disorders (OUD). Its unique pharmacological properties help reduce the potential for misuse and diminish the effects of physical dependency on opioids, including withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Similar to opioids, it can generate euphoria and respiratory depression when administered at low to moderate doses; however, these effects are weaker than with other opioid agonists. Therefore, buprenorphine (Sublocade) increases patient safety in the event of an overdose. The opioid effects of buprenorphine (Sublocade) increase with each dose but level off with moderate amounts, even if further dosing increases. This "ceiling effect" helps lower the risk of misuse, dependency, and side effects. Some of the most common side effects of buprenorphine (Sublocade) include nausea, vomiting, constipation, muscle cramps, inability to sleep, cravings, distress, irritability, and fever (SAMHSA, 2023).

An opioid agonist-antagonist refers to an opioid with mixed actions. These drugs produce different activities at different receptors, acting on one opioid receptor to create a response and binding to another to prevent a response. Medications in this class demonstrate varying activity depending on the targeted receptor and the dose. Some examples of agonist-antagonists include pentazocine/naloxone (Talwin) and butorphanol (Stadol). Pentazocine/naloxone (Talwin) is used to treat moderate to severe pain and contains two medications. It acts by binding to and activating specific opioid receptors while simultaneously blocking the activity of other opioid receptors. The naloxone component of the drug helps prevent misuse of the medication. Pentazocine (Talwin) is unavailable in the US as a single agent. Butorphanol (Stadol) is a mixed opioid agonist-antagonist available as a spray for treating migraine headaches. Similar to partial agonists, agonist-antagonist opioids have a ceiling effect. Therefore, they offer lower analgesic efficacy and a heightened risk for psychotomimetic or psychotogenic effects or symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations and delirium (Berger & O'Neill, 2022).

In addition to the signs and symptoms listed for all CNS depressants, opioid intoxication causes a reduced sensation of pain, agitation, constricted or pinpoint pupils, and a lack of awareness of surroundings. They can also provoke respiratory depression, nausea/vomiting, HA, fatigue, pruritus, and urinary retention. These drugs can induce euphoria, especially when taken in higher doses than prescribed or ingested via snorting or injection, putting them at increased risk for abuse and addiction. Long term, the patient may also exhibit constipation, a runny nose/nasal lesions (if snorting medication), needle/track marks (if injecting), drug tolerance, and hyperalgesia, which is increased sensitivity to pain caused by damage to nociceptors or peripheral nerves. A severe opioid overdose will eventually present with loss of consciousness and, if anoxia develops, pupillary dilation. Withdrawal may develop within 6-12 hours of short-acting opioids such as heroin, peak within 1-3 days, and resolve within a week. With long-acting opioids such as methadone, withdrawal symptoms may take 2-4 days to begin. Signs and symptoms of withdrawal from opioids may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dysphoric mood, muscle aches, rhinorrhea/lacrimation, sweating, dilated pupils, piloerection (involuntary erection of body hairs), yawning, fever, and insomnia. The patient may report feeling anxious or restless. Chronic symptoms of anxiety, dysphoria, anhedonia (lack of pleasure), and insomnia may last weeks to months (APA, 2022; Dixon, 2022; O'Malley, 2022e). The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) is an 11-item scale that assesses for common withdrawal symptoms (NIDA, 2023b).

The risks for opioid use during pregnancy are further increased. Cycles of opioid use cause repeated withdrawal periods, resulting in reduced placental function and neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Opioid use increases the risk of maternal infection, malnutrition, poor prenatal care, violence, and incarceration; it can lead to restricted growth, preterm labor, fetal convulsions, and death in severe cases. NAS results in withdrawal in newborns after delivery, presenting with tremors, diarrhea, fever, irritability, seizures, and difficulty feeding (NIDA, 2020c).

Sedatives/Anxiolytics/Hypnotics/Tranquilizers

As mentioned, the NSDUH found roughly 1.4 million current (i.e., within the past month) prescription sedatives, tranquilizers, hypnotics, and anxiolytics users in 2021 (SAMHSA, 2022). Many of these medications are prescribed for anxiety disorders, insomnia, and similar conditions requiring medication to induce relaxation, reduce heart rate, reduce blood pressure, and induce sleep. The most common options consist of BZD medications such as diazepam (Valium), clonazepam (Klonopin), lorazepam (Ativan), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), and alprazolam (Xanax). They may be used for panic attacks or, despite warnings to the contrary, to treat chronic anxiety. Some may be used to treat seizures or as a muscle relaxant or a sleep aid. BZDs function by binding to benzodiazepine receptors and enhancing the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), our primary inhibitory neurotransmitter. They carry a high risk for tolerance, dependence, and addiction, so they are only recommended for short-term or acute use. Non-BZD sleep medications (hypnotics) include zolpidem (Ambien), eszopiclone (Lunesta), and zaleplon (Sonata). These drugs affect the same GABA type A receptors but have a different chemical structure than BZDs, decreasing the risk of dependence and improving their side effect profile. Barbiturates—such as phenobarbital (Luminal), pentobarbital (Nembutal), secobarbital (Seconal), and mephobarbital (Mebaral)—are potent sedatives/hypnotics typically reserved for emergent seizure disorder treatment and procedural sedation. They alter the brain's sensory cortex, cerebellar, and motor activities. Initial adverse effects include drowsiness and ataxia; as tolerance develops, these symptoms may dissipate (NIDA, 2020b). In addition to the intoxication symptoms apparent with all CNS depressants, intoxication with these drugs can also suppress deep tendon reflexes and cause nystagmus, slurred speech, irritability, unsteadiness, and ataxia, leading to an increased risk of falls. Severe intoxication can lead to respiratory depression, confusion, coma, and death (APA, 2022; O'Malley, 2022f).

Acute withdrawal from BZDs and barbiturates can be life-threatening, resulting in seizures and other complications (NIDA, 2020b). Symptoms such as autonomic hyperactivity (sweating, tachycardia), tremors, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, transient hallucinations, psychomotor agitation, anxiety, and seizures can develop within several hours to a few days. Seizures may be seen in as many as 20%-30% of those going through untreated withdrawal from these medications. The duration of withdrawal symptoms varies based on the half-life of the substance. Substances that last 10 hours or less, such as lorazepam (Ativan) and temazepam (Restoril), typically peak on the second day and improve by day 5. Medications with longer half-lives, such as diazepam (Valium), may not produce withdrawal symptoms for a week, peak during the second week, and improve during the third or fourth week. Chronic symptoms of withdrawal can continue for months (APA, 2022).

Stimulants

Prescription stimulants are used to treat conditions such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy (a sleep disorder), severe depression, and chronic diseases that cause fatigue, such as multiple sclerosis (MS). They help improve alertness, attention, and energy. Common adverse effects include tachycardia, hypertension, and tachypnea. Previously, stimulants were used for several other conditions, but their use has been reduced as the risk for addiction became evident. Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, Adderall) and methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) enhance the effects of norepinephrine and dopamine in the brain. The enhancement of dopamine can result in a feeling of euphoria. The effects of norepinephrine include hypertension, tachycardia, constriction of blood vessels, increased blood glucose, and bronchodilation. The public perception of the relative safety and benign nature of these medications has likely contributed to their misuse and abuse in the last few decades. Patients and their caregivers/parents should be adequately educated regarding the potential risks of nonprescription drug use, such as unsafe driving, unsafe sexual activities, and a progression to illicit substances. Non-therapeutic stimulants include cocaine and methamphetamine (NIDA, 2020b; Via, 2019).

Stimulant use can produce rapid/rambling speech, hallucination, irritability, anxiety, increased alertness, euphoria, and impaired judgment. Stimulant intoxication presents with tachycardia or bradycardia, pupillary dilation, hypotension or hypertension, diaphoresis, chills, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, psychomotor agitation/retardation, weakness, respiratory depression, chest pain, confusion, seizures, dyskinesia, dystonia, and coma. Chronic use can lead to feelings of hostility, paranoia, psychosis, arrhythmias, hyperthermia, cardiovascular failure, and seizures. These symptoms, especially hypertension and arrhythmias, may also present acutely if prescription stimulants are combined with certain over-the-counter decongestants. If stimulants are snorted, nasal congestion, epistaxis, or ulceration of the mucous membranes can result. If the medication is being smoked, it often results in mouth sores, gum disease, and tooth decay (i.e., meth mouth) due to poor oral hygiene, decreased saliva production, and teeth grinding (APA, 2022; NIDA, 2020b; O'Malley, 2022a).

There is no stereotypical patient presentation for stimulant withdrawal; however, chronic users who abruptly stop taking stimulants may present with fatigue, dysphoric mood, hypersomnia or insomnia, irritability, and bradycardia. Patients may also report vivid/unpleasant dreams, increased appetite, anhedonia, and psychomotor retardation or agitation. These symptoms typically present within a few hours to days of the last use and are accompanied by cravings for the drug. No medication is available to treat the effects of amphetamine withdrawal (APA, 2022; NIDA, 2020b; O'Malley, 2022a).

Hallucinogens

Recreational hallucinogens include 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy, or Molly), ketamine (Special K), D-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and phencyclidine (PCP). Less common hallucinogens include phenylalkylamines (similar to MDMA) such as mescaline (peyote) and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM), indoleamines such as 4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (psilocybin, psilocin, or magic mushrooms), 5-methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine (5-MeO-DIPT), N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), morning glory seeds (an ergoline similar to LSD), dextromethorphan (DXM), Salvia divinorum, jimsonweed, 251-NBOMe, and others. Hallucinogens can be ingested via pills or liquid, chewed, brewed into tea, snorted, injected, inhaled/smoked, or absorbed via the oral mucosa from a drug-impregnated paper. Most hallucinogens affect the neurotransmitter serotonin. Synthetic cathinones, frequently referred to as bath salts, are chemically similar to Khat, a shrub whose leaves are chewed on in East Africa and southern Arabia for the stimulant effects. Synthetic cathinones can be taken orally, snorted, inhaled, or injected. The effects are much stronger than those produced by the Khat leaves and are similar to MDMA and cocaine. They are highly addictive, and users report a strong, uncontrollable urge to use the drug (APA, 2022; NIDA, 2020d, 2021a; O'Malley, 2022c).

Hallucinogen use may present with hallucinations, paranoia, dilated pupils, chills, sweating, tremors, muscle cramping, teeth clenching, impulsive behavior, emotional lability, dry mouth, nausea, ataxia, blurred vision, tachycardia/palpitations, hyperthermia, hypertension, and a heightened or altered sense of sight, sound, and taste. These symptoms typically appear within 20-90 minutes of ingestion and last anywhere from 15 minutes (synthetic DMT) to 12 hours (LSD). PCP, ketamine, DXM, and similar agents can also cause dissociation (a feeling of being separated from the body), ataxia, aggression/violence, muscle rigidity, nystagmus, decreased perception of pain, dysarthria, impaired judgment, intolerance to loud noise (hyperacusis), seizures, and coma. Dissociative agents function by affecting the action of glutamate. Life-threatening overdoses are rare with hallucinogens, but seizures, coma, and fatalities have been reported with 251-NBOMe and PCP use. Due to poor judgment and contamination, users of hallucinogens are also at an increased risk of injury and accidental poisoning. Substituted cathinones will typically present with many of the hallucinogen symptoms mentioned earlier, as well as symptoms of stimulants such as euphoria, increased sociability, increased energy, heightened sex drive, and psychotic/violent behavior. Users may experience loss of muscle control, panic attacks, and delirium (APA, 2022; NIDA, 2021a; O'Malley, 2022c).

Long-term hallucinogen use leads to permanent mental alterations, especially in perception, and possible flashbacks. Persistent psychosis, which includes visual disturbances, mood changes, paranoia, and disorganized thinking, has been reported. Hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder (HPDD) refers to subsequent hallucinations or flashbacks, which may occur days or years after drug use. Persistent psychosis and HPDD are seen more often in patients with a history of mental illness but can affect any user. Dissociative agents can lead to speech problems, weight loss, memory loss, chronic anxiety/depression, and suicidality. Repeated use of LSD can lead to tolerance, and PCP users may develop addiction and subsequent withdrawal, with reports of cravings, headaches, and sweating (APA, 2022; NIDA 2021a; O'Malley, 2022c).

Tobacco, Cannabis, and Other Inhalants

As previously mentioned, according to the NSDUH, nearly 43.6 million (15.6%) Americans smoked cigarettes (27.0 million daily), and roughly 10.3 million smoked cigars in 2021 in the past month. Due to the increase in vaping, this statistic was included in the survey beginning in 2020. In 2021, 13.2 million individuals used nicotine via vaping (11.2 million of those only vaped and did not use any tobacco products). More people (52.5 million) reported marijuana use in the last year; of these, 36.4 million reported use in the previous month (SAMHSA, 2022).

Tobacco

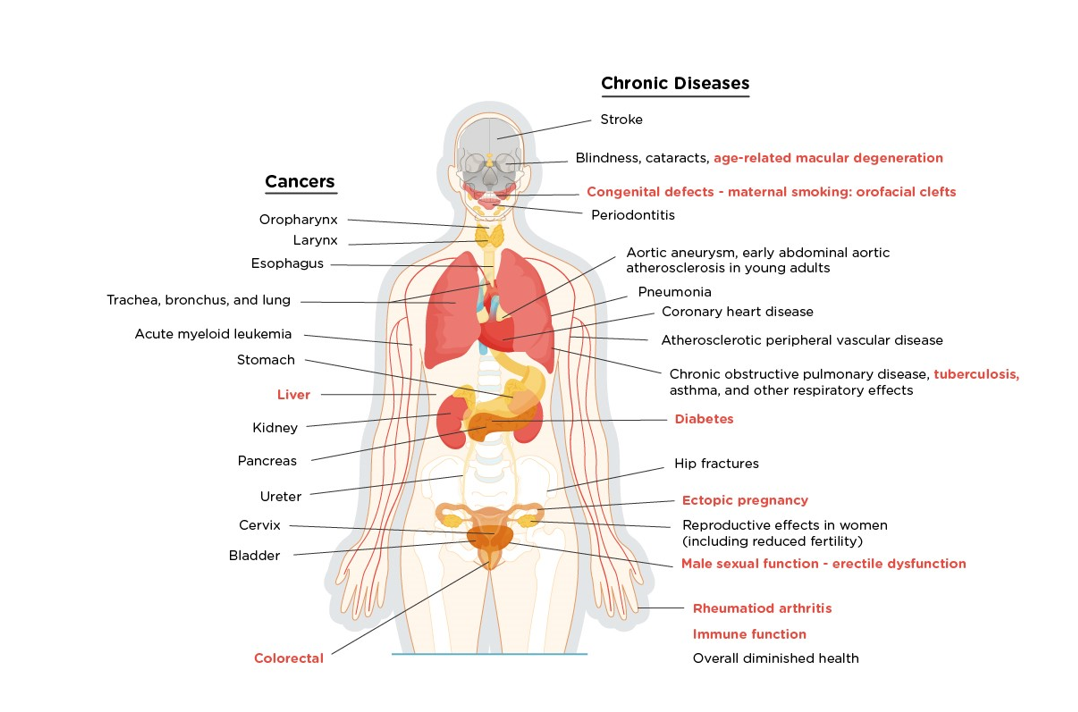

Despite the well-known effects of smoking and the use of tobacco and nicotine-containing products (see Figure 1), usage in the US persists in large numbers, mainly due to the highly addictive nature of nicotine.

Figure 1

Health Consequences Causally Linked to Smoking

Note: The conditions in red are new diseases that were causally linked to smoking in this report.

(Information from the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2014)

Legislation passed in 2019 increased the legal age of purchasing nicotine and tobacco products to 21 in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Many individuals in the US experiment with tobacco, approximately 4.3 million (11%) of individuals report current (past month) use by age 21, and most of these young adults become daily smokers. Initiation after the age of 21 is rare. Patients may report nausea and dizziness initially with tobacco use, but these symptoms resolve quickly as tolerance develops. Tobacco intoxication is not a phenomenon, but tobacco withdrawal may present within 24 hours of cessation with symptoms such as irritability, anxiety, lack of mental focus/concentration, increased appetite (especially for salty or sweet foods), restlessness, depressed mood, constipation, dizziness, and insomnia. Some smokers also report increased coughing and sore throat immediately after quitting. Withdrawal symptoms typically peak after 2-3 days and resolve within 2-3 weeks (APA, 2022; SAMHSA, 2022).

Cannabis

The terms cannabis or marijuana are often used interchangeably to refer to drugs produced from plants belonging to the genus Cannabis; however, cannabis describes any product that can be derived from the plant, while marijuana refers explicitly to products from the plant high in delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Three specific species have been identified: Cannabis sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis. Cannabis history began approximately 12,000 years ago in central Asia. There is recorded cannabis use in ancient China, Egypt, Greece, and the Roman Empire. It was listed in the US Pharmacopeia from 1851-1937, but then measures began being implemented to restrict its use. In 1937, the Marihuana Tax Act was passed in the US. Then in 1961, marijuana was classified as dangerous and without significant medical use by the United Nations (UN) Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. In 1970, cannabis was categorized by the DEA's Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (Controlled Substances Act) as a Schedule I drug in the US, meaning it has a high potential for abuse and no accepted medicinal use, making any further research significantly more complicated to conduct (Crocq, 2020; National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [NCCIH], 2019).

The two most biologically active phytocannabinoids, THC and cannabidiol (CBD), directly affect the endocannabinoid receptors CB1R and CB2R. While THC is responsible for most of the drug's psychoactive properties, CBD is considered non-addictive and non-psychoactive and potentially contains anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties. The primary mechanism of action for CBD is mainly unknown. It continues to be studied, as it does not seem to be primarily mediated via the CB1 and CB2 receptors due to CBD's low affinity (Crocq, 2020).

As of February 2023, there are comprehensive medical marijuana access laws in 37 states and the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. Ten additional states allow the use of "low THC, high CBD" products for medical reasons in specific situations, despite cannabis's continued classification as a Schedule I drug by the federal government. Also, 21 states, 2 territories, and the District of Columbia have legalized adult use of cannabis, allowing for recreational use without medical certification. There are no marijuana access laws currently in Idaho, Nebraska, and Kansas (The Council of State Governments, 2023).

Cannabis effects may vary depending on how it is ingested (smoking, eating, vaping). Onset is within minutes when smoked and typically lasts 3-4 hours; when ingested orally, the onset is delayed, and symptoms are often prolonged. Symptoms associated with marijuana use can include:

- euphoria

- heightened perception (visual, auditory, or taste)

- tachycardia

- hypertension

- dry mouth

- conjunctival injection

- ataxia, slowed reaction time

- difficulty concentrating

- loss of short-term memory

- anxiety/paranoia

- increased appetite with exaggerated cravings for certain foods (“munchies”; APA, 2022; O'Malley, 2022d)

Patients may also present with a distinct odor on their clothing and yellowing of the fingertips, similar to tobacco smokers. Long-term use may result in decreased mental acuity, performance issues at work/school, reduced extracurricular interests or friends, depression, anxiety, and hyperemesis. Synthetic cannabinoids—including HU-210, JWH-073, JWH-018, JWH-200, AM-2201, UR-144, and XLR-11—are being produced regularly. The substances are often called K2 or Spice and may be sprayed on dried herbs and smoked or made into an herbal tea. It can create many of the aforementioned cannabis symptoms, as well as hallucinations, vomiting, confusion, agitation, hypertension, tachycardia, myocardial infarction, and psychosis that may be irreversible (O'Malley, 2022b, 2022d).

Withdrawal symptoms may develop within 24-72 hours following cessation, including depressed mood, irritability, aggression/anger, anxiety, insomnia, unpleasant dreams, weight loss/decreased appetite, restlessness, abdominal pain, tremors, sweating, fever/chills, fatigue, and headaches. These symptoms peak at 2 to 3 days and last approximately a week, although sleep disturbance can persist for up to 30 days (APA, 2022; O'Malley, 2022d).

Despite its low perceived threat (only 26.5% of survey respondents reported a significant risk related to weekly marijuana use), the NSDUH estimates that roughly 16.3 million (5.8%) meet the diagnostic criteria for SUD based on their use of cannabis. Of those, 57.6% had a mild disorder compared to 16.1% who had a severe disorder (SAMHSA, 2022).

Inhalants

The 2021 NSDUH report estimates that 830,000 individuals used inhalants in the last month, and about 2.2 million (0.8%) reported use in the previous year. The rate of inhalant use was highest among adolescents aged 12-17 at 2.4% or 626,000 individuals (SAMHSA, 2022). This term typically refers to volatile solvents such as acetates, chloroform, and aliphatic or aromatic hydrocarbons. These are toxic gases found in glues, paints, paint strippers, and cleaning fluids. Other items include correction fluid, felt tip markers, gasoline, and household cleaners/aerosol products (O'Malley, 2022g). Symptoms of intoxication may vary depending on the specific substance but typically include:

- dizziness

- nystagmus

- ataxia/unsteady gait

- dysarthria

- diminished reflexes/psychomotor retardation

- tremor

- muscle weakness

- blurred vision/diplopia (double vision)

- euphoria/intoxication

- decreased inhibition

- combativeness/belligerence

- nausea/vomiting

- arrhythmia

- lethargy, stupor, or coma (APA, 2022; O'Malley, 2022g)

In severe cases, brain damage and death are possible. Symptoms typically resolve within a few minutes to hours, and withdrawal syndrome is rare. Patients may also present with an unexplained rash around the mouth and nose. The abuse of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is included within the NSDUH definition of inhalants but is considered separately by the APA in the DSM-5-TR as “other.” It is used therapeutically as an anesthetic for medical and dental procedures and commercially as a propellant in products such as whipped cream dispensers (i.e., whippets). Chronic heavy use can result in myeloneuropathy, spinal cord subacute combined degeneration, peripheral neuropathy, and psychosis (APA, 2022; O'Malley, 2022g; SAMHSA, 2022).

Effective Management/Treatment

Overdose or Acute Withdrawal Management

As mentioned earlier, acute alcohol, BZD, and barbiturate withdrawal—specifically severe alcohol withdrawal with DT and barbiturate withdrawal—can be life-threatening. These patients should undergo medically supervised detoxification and be managed with tapered doses of BZDs (i.e., chlordiazepoxide [Librium]) and potentially barbiturates to limit withdrawal symptoms and avoid seizures, which typically improve after 4-5 days. Lorazepam (Ativan) is the preferred agent in patients with liver dysfunction. For BZD overdose, emergency medical personnel can administer flumazenil (Romazicon), a BZD antagonist, intravenously (APA, 2022; MedlinePlus, 2021; NIDA, 2020b).

In 2021, 80,411 individuals died as a result of an opioid overdose (NIDA, 2023a). Naloxone (Narcan) is the most widely used opioid antagonist, as it is FDA-approved for opioid overdose. It is highly effective in reversing opioid overdose and respiratory depression and is available in intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), subcutaneous (SC), and intranasal (IN) formulations. When administered intravenously, effects begin almost instantly and last for about an hour. Still, the dose should be titrated to reverse respiratory depression without completely reversing the analgesic effects. Rapid infusion of the medication should be avoided to reduce the risk of hypertension, tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting. Vital signs should be monitored, especially respirations, and naloxone (Narcan) administration should be repeated until the manifestations of opioid toxicity have subsided (Theriot et al., 2022). With IM and SC administration, the drug takes effect in 2-5 minutes and has a half-life of 30 to 81 minutes. These administration routes are most commonly used by emergency medical services (EMS) personnel and civilians responding to opioid overdose in the community. According to the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS), the number of EMS responses to opioid overdoses was 185,979, and the rate of nonfatal opioid overdoses was 56.4 per 100,000 people from February 2022 to 2023. The average number of naloxone (Narcan) administrations per overdose was 11 in that same period (NEMSIS, 2023).

Naloxone (Narcan) has become increasingly available to the public, as its prescribing and dispensing have become a central part of the public health response to the opioid overdose epidemic. Legislation has also been passed to protect laypersons who assist an individual with a suspected opioid overdose. In addition, most states now allow naloxone (Narcan) to be purchased from a pharmacy without a prescription. Prescribers are advised to consider prescribing a concurrent prescription for naloxone (Narcan) for patients who are at high risk for intentional or accidental overdose (NIDA, 2022a; Theirot et al., 2022). Those considered to be at the highest risk include patients who meet any of the following criteria:

- doses of > 50 MME/day

- chronic opioid use

- concurrent use of sedatives

- personal history of SUD

- family history of substance abuse/SUD

- patients being treated with opioids who live in isolated or rural areas

- those with severe medical such as chronic respiratory disease, HIV/AIDS, or chronic renal, hepatic, or cardiac disease

- current or past history of depression or other serious mental health conditions

- male gender

- between the ages of 20 and 40

- white. non-Hispanic ethnicity

- using opioids after a period of abstinence (Schiller et al., 2022)

Serious adverse effects of naloxone (Narcan) are rare; usually, the benefit of using it for an overdose outweighs the risk for adverse effects. However, it can induce acute opioid withdrawal symptoms such as tachycardia, agitation, vomiting, body aches, and convulsions. Naloxone has no reversal effect on tramadol (Ultram), alcohol, or other CNS depressants such as BZDs (NIDA, 2022a).

Long-Term Management

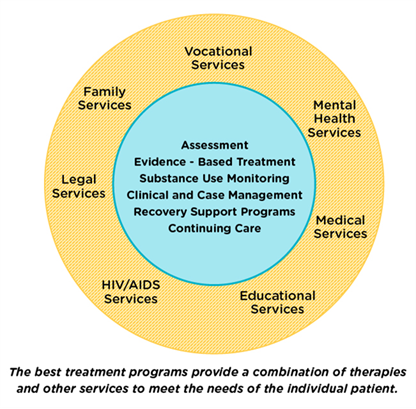

Ideally, SUD treatment should consist of detoxification, counseling, and medications. In reality, it may require multiple attempts before full recovery is achieved. It should also include effective treatment for any comorbid mental health conditions other than addiction and long-term follow-up to prevent and manage relapses. Legal services, educational/vocational services, infectious disease screening/referrals, and case management should also be components (see Figure 2; NIDA, 2019b, 2020b).

Figure 2

Components of Comprehensive Drug Addiction Treatment

Brief intervention (BI) is an appropriate engagement for most SUD patients. It encourages a patient to recognize the problem with substance use and engages them in positive change. It typically lasts 5-15 minutes and consists of brief advice via motivational interviewing techniques (Pearson & Duff, 2019). The FRAMES acronym is a commonly used technique:

- Feedback of risk

- Encouraging responsibility for change

- Advice

- Menu of options

- Therapeutic empathy

- Enhancing self-efficacy (Pearson & Duff, 2019)

BI is a component of SBIRT, an evidence-based method of screening patients and briefly providing education and motivation to change, with an associated referral for additional treatment. SBIRT is meant to be brief, universal, comprehensive, targeted, and performed outside of a substance abuse treatment setting. Once granted permission to discuss alcohol/tobacco/drug use by the patient, providers should begin SBIRT with a validated screening tool to assess risk, which provides the basis for the feedback on risk (step #1 above). The brief counseling session should include an exploration of ambivalence, enhance motivation, and facilitate shared goal setting (if applicable) by first defining healthy patterns of use/behavior and then drawing a clear distinction with the patient's current use/behavior in a nonjudgmental manner. The discussion should be collaborative, with questions regarding how the patient perceives any benefits and potential risks of their substance use. Abstinence is not a goal, but questioning whether the patient is interested in and ready to change their behavior is appropriate. If the answer is yes, the provider may ask the patient to gauge their motivation using a 1-10 scale. A patient unwilling or not ready to make a behavioral change should be treated with respect and dignity and reassessed later. A comprehensive substance-related history should be completed if screening tools are positive, with questions regarding onset, duration, characteristics, precipitating factors, other substances used, and withdrawal symptoms (Albrecht et al., 2019).

Goal setting is associated with improved outcomes, as are nonpharmacological lifestyle changes such as establishing a consistent sleep schedule, exercising regularly, avoiding triggers (situations, people, or places associated with the substance of abuse), engaging in a new hobby/interest to prevent boredom, and spending time with supportive friends and family members. Both inpatient and outpatient treatment programs should be explored/considered; both should consist of some combination of sessions with an addiction counselor, behavior therapies, group therapies, and psychotherapy (Pearson & Duff, 2019). For the treatment of most SUDs, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been effective. CBT attempts to modify a patient's unhealthy thought and behavior patterns and develop strategies to manage cravings and avoid triggers. Some forms of therapy also provide incentives for abstinence. Behavioral treatments may be individual or occur with their family or in a group setting. The goal is to improve relationships and functionality at work, at home, and in the community. Motivational incentives (contingency management) designed to use positive reinforcement to encourage abstinence may also be used. In 2018, reSET, the first mobile application designed as an adjunct for SUD outpatient treatment, was approved for marketing by the FDA for patients struggling with addiction to alcohol, marijuana, and stimulants, including cocaine. Opioid addiction was added to the platform in 2018, designed to be used along with buprenorphine (Sublocade) for a remote-style MAT (NIDA, 2019b, 2020b).

Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorder

While the acute treatment of overdoses can save lives, preventing overdoses and treating opioid use disorder would be exponentially better for public health and the health of individuals suffering from an overdose. Although effective treatment strategies are available, they are underutilized in the US. Larochelle and colleagues (2018) assessed over 17,000 adults who had suffered an opioid overdose between 2012 and 2014. When treated appropriately with MAT during the first year after their overdose, subjects showed a 59% reduction in overdose deaths when using methadone (Dolophine) and a 38% reduction with buprenorphine (Sublocade). Unfortunately, less than 33% of the study participants received MAT, 34% were prescribed another opioid, and 26% were prescribed a BZD during the 12 months following their overdose. Only 11% of participants received methadone (Dolophine) for an average of 5 months, 17% received buprenorphine (Sublocade) for an average of 4 months, and 6% received naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia), which was too limited to obtain a statistically significant reduction in overdose deaths (Larochelle et al., 2018).

Pharmacological treatment for moderate to severe AUD may consist of 1 of 3 FDA-approved medications: naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia), acamprosate (Campral), and disulfiram (Antabuse). Naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia) is an opioid antagonist used to treat substance use disorders, namely AUD and OUD. It also can treat postoperative respiratory depression due to the use of opioids during the operative period. When used for OUD or AUD, its purpose is to prevent euphoria and decrease the desire/craving to use opioids or alcohol. A patient should be opioid-free for 7-10 days before beginning the medication to avoid opioid withdrawal syndrome, making this option difficult for some. It is available as a long-acting injection every 4 weeks. Despite this convenient delivery method and the fact that any licensed prescriber can prescribe it, it is used less commonly than methadone (Dolophine) and buprenorphine (Sublocade) for the treatment of OUD (Moore, 2019; Theriot et al., 2022). Abstinence from alcohol before starting naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia) is associated with better outcomes in the treatment of AUD but is not required. Naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia) use is contraindicated in patients with liver failure. Liver transaminase levels (AST and ALT) should be assessed before starting and periodically during treatment and should be withheld if over 3 times the upper limits of normal. Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, HA, dizziness, insomnia, depression, and muscle cramps (Pearson & Duff, 2019).

Acamprosate (Campral) is also approved as a first-line treatment for moderate to severe AUD, functioning as an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, an excitatory neurotransmitter. It appears to function better if started 4-7 days after abstaining from alcohol, but this is not required. It must be dosed 2-3 times daily and stopped after 4-6 months if no effect is noted. It is safe for patients with impaired liver function but not severe renal dysfunction. Prescribers should monitor liver/renal function, as well as for depression and suicidality. Adverse effects include anxiety, stomach upset, HA, and muscle weakness. Both naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia) and acamprosate (Campral) are contraindicated in pregnancy. Naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia) works best for craving management and binge drinking, while acamprosate (Campral) appears best for abstinence maintenance. If neither of these is effective for patients with AUD, off-label alternatives are listed in Table 3 (Pearson & Duff, 2019).

Table 3

Additional Medications for the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder

Medication | Dosing | Mechanism of Action | Adverse Effects | Contraindications | Suggested Monitoring |

Disulfiram (Antabuse) | 500 mg daily initially for 1-2 weeks, then 125-250 mg daily | Prevents conversion of acetaldehyde to acetic acid, causing flushing, HA, and nausea/ vomiting when combined with any alcohol | HA, rash, metallic taste in the mouth, fatigue, arrhythmias (not often used due to severe reaction with alcohol) | Older adults, cardiovascular disease, psychosis, pregnancy, and liver disease; must be alcohol-free for at least 24 hours prior to starting | Liver function tests (LFTs), complete blood count (CBC), electrolyte panel |

Topiramate (Topamax) | 25 mg daily initially, titrate up weekly as needed, max 300 mg daily | Antiepileptic drug (AED) that inhibits dopamine release with alcohol ingestion, reducing compulsivity, cravings, depression, and anxiety | Paresthesia, cognitive impairment, fatigue, weight loss, diarrhea, depression | Pregnancy | Serum creatinine, depression; alcohol ingestion exacerbates CNS depression |

Gabapentin (Neurontin) | 300 mg daily initially, titrate up over 1-2 weeks, typical dose 3-600 mg TID | AED that inhibits dopamine release to decrease heavy drinking and increase days of abstinence | Dizziness, drowsiness, tremor, muscle weakness, and weight gain | Renal dysfunction, should be alcohol-free for 7 days prior to starting | CNS depression/ sedation, serum creatinine |

Baclofen (Gablofen) | 5 mg TID initially, titrate up q3 days, typical dose 10-25 mg TID (higher doses more effective) | Antispasmodic that blocks the mesolimbic reward system and may decrease heavy drinking days and increase days of abstinence | Hypotonia, drowsiness, nausea, HA, confusion, dizziness, pruritis | Should be tapered slowly over 2 weeks when stopping to limit seizure risk | CNS depression/ sedation |

(Pearson & Duff, 2019)

Weekly or biweekly visits are encouraged to assess medication effects and treatment plan adherence, provide ongoing support, and discuss drinking/craving patterns. APRNs should assess each patient’s overall health, mental status, family/social activities, work status, and legal status. Relapses are common, and APRNs should share this information with each patient, along with encouragement to continue efforts and view the relapse as a “stepping-stone to wellness” and not as a failure or defeat (Pearson & Duff, 2019).

MAT is an example of a holistic, patient-centered approach to treating SUD. Medication, counseling, and behavioral therapies are combined, resulting in improved survival rates, extended treatment periods, decreased illicit opioid use and criminal activity, and a reduced risk of contracting an infectious disease (HCV, HBV, HIV) or developing an abscess. The three FDA-approved medications for OUD are buprenorphine (Sublocade), methadone (Dolophine), and naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia). Critics of MAT claim that the treatment replaces one drug with another (Moore, 2019). The use of MAT in incarcerated patients improves post-release outcomes (NIDA, 2020b).

The partial opioid agonist buprenorphine (Sublocade) was first approved by the FDA in 2002 when combined with counseling and behavioral therapies to treat OUD. It has a half-life of approximately 24 hours. It may cause mild euphoria in some patients but is designed with the ceiling effect to limit its abuse potential. It may also cause respiratory depression when combined with BZDs or other CNS depressants. There are a few types of buprenorphine approved for use by the FDA, which include a monthly subcutaneous injection (Sublocade), a subdermal implant that lasts for 6 months (Probuphine), buprenorphine/naloxone (Bunavail, Suboxone) sublingual or buccal film, and buprenorphine/naloxone (Zubsolv) sublingual tablets. The combination products are used most often, as the addition of naloxone effectively blocks attempts at misuse. The naloxone component, an opioid antagonist, is not well absorbed through the oral mucosa. However, if the tablets/films are crushed or melted for injection or any other delivery method, the naloxone component blocks the effects of all opioids. Buprenorphine (Sublocade) is not without risk, as some patients may divert the drug or combine it with a BZD to augment the euphoric effects, creating a potentially lethal combination. Random urinary drug tests (UDTs) may help screen for and identify patients who are combining other medications or diverting/selling their prescription and not taking it at all. Consistent use of available prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) will also help APRNs identify patients who are obtaining prescriptions elsewhere. There are also reports of significant difficulty obtaining a supply of the medication, as many pharmacies do not want to carry large stockpiles of the medication in combination with a system-wide drug shortage. Overall, overdoses are rare, and some studies indicate that buprenorphine (Sublocade) is 6 times safer than methadone (Dolophine). With regards to dosing, it is a long-acting agent and requires only daily dosing for many patients (Moore, 2019; SAMHSA, 2023)

Buprenorphine (Sublocade) treatment does not require close monitoring in the highly structured environment of methadone (Dolophine) based clinics. Trained and certified physicians and APRNs can prescribe it in an office setting, as it is considered safe and effective when taken as prescribed. Historically, prescribing the medications used for MAT required an additional prescribing waiver. In 2015, only half of US counties had a qualified licensed physician (called waivered) to prescribe buprenorphine. At the end of 2022, President Joseph Biden signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, which included the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act (MAT Act) as a provision. This provision removes the barriers to prescribing MAT medications, allowing any provider permitted to prescribe controlled substances the ability to prescribe buprenorphine (Sublocade) for the treatment of OUD (National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, 2023). Most providers utilize COWS to assess when to initiate buprenorphine (Sublocade). Due to its high affinity for mu-opioid receptors, it should ideally be started when a patient is experiencing mild to moderate withdrawal (score of 6 to 12 on the scale). Home-based or unobserved treatment inductions supported by extensive patient education and preparation are possible and becoming more common. A treatment duration of 2 years is recommended by most clinical experts (Moore, 2019; SAMHSA, 2023). Studies indicate that starting buprenorphine (Sublocade) in an ED immediately after the initial treatment for an opioid overdose is more effective than a referral or BI (NIDA, 2020b).