This course provides an overview of tobacco dependence, its effects on health, and interventions to prevent and treat tobacco use. It offers advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) guidance and resources to help patients with smoking cessation.

...purchase below to continue the course

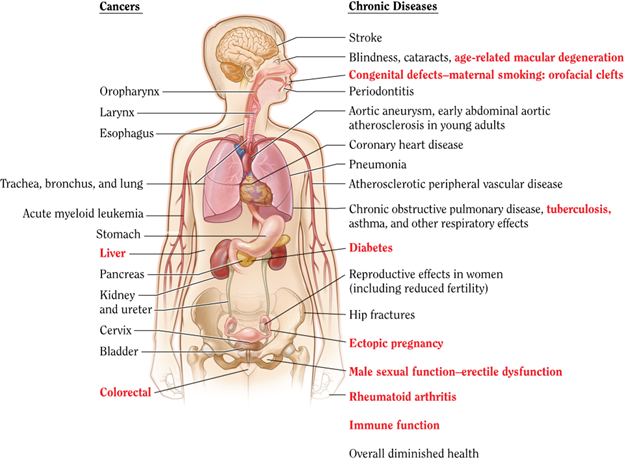

a 30% higher risk of CVD and stroke than their nonexposed counterparts (CDC, 2024c; HHS, 2020). Smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period increases the risk of premature birth, low birth weight, and sudden unexpected infant death syndrome (SUIDS). Prenatal nicotine exposure has been shown to affect lung development (Rodriguez, 2024). In addition to SUIDS, children exposed to secondhand smoke have increased risks of experiencing middle ear disease, impaired lung function, and other acute and chronic respiratory illnesses (CDC, 2023a, 2021, 2024c; HHS, 2020; Rodriguez, 2024).

Ingredients in Tobacco and Cigarette Smoke

Nicotine was originally extracted from the plant Nicotiana tabacum, a tropical herb now cultivated globally for commercial purposes (McMurtrey, n.d.). There are about 600 ingredients in cigarettes, and tobacco smoke produces more than 7,000 different chemicals, nearly 70 of which are known carcinogens (cancer-causing substances). Some of the chemical constituents of cigarettes are outlined in Table 1 (American Lung Association, 2023; McMurtrey, n.d.).

Table 1

Chemical Composition of Cigarettes

Chemical | Description |

Nicotine | - Colorless, poisonous substance derived from the tobacco plant

- Affects the brain and becomes highly addictive very quickly

|

Carbon monoxide (CO) | - Colorless, odorless, toxic gas released from burning tobacco

- Enters the bloodstream and interferes with the heart and blood vessels

- A smoker’s blood can carry up to 15% CO instead of oxygen

|

Tar | - Material used for paving roads

- Sticky brown substance that forms when tobacco cools and condenses

- Collects in the lungs and can lead to cancer

|

Ammonia | - Toxic, colorless gas with a strong, sharp odor

- Commonly found in fertilizers and household cleaning products

- Boosts the impact of nicotine in cigarettes

|

Arsenic | - Frequently found in rat poison

- Arsenic-containing pesticides utilized in tobacco farming appear in small quantities of cigarette smoke

|

Toluene | - Highly toxic chemical used to manufacture paint, rubber, resin, adhesive, ink, detergents, and explosives

|

Acetone | - Colorless solvent used to manufacture many industrial products

- Also found in nail polish remover

|

Formaldehyde | - Strong-smelling, colorless gas used to manufacture building materials, household products, and other chemicals

- Embalming fluid (liquid used on dead bodies to disinfect, preserve, and sanitize)

|

Methanol | - Fuel utilized by the aviation industry

|

- (American Lung Association, 2023)

The Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs last convened an international expert panel in 2014 to rank 12 nicotine-containing products based on their relative harm using the multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach. Their findings revealed that cigarettes are by far the most harmful (with a score of 100 out of 100) to individuals who use them and those around them based on 14 independent criteria. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products, such as patches and nasal sprays, received low scores of 2, whereas small cigars (score 64), pipes (score 21), cigars (score 16), and water pipes (score 14) carried additional harm. This committee credited the bulk of smoking’s damage to CO, tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs), and nitric oxide (Nutt et al., 2014). A separate study of toxicant exposure in combustible tobacco products (CTPs) listed the potent toxins found in cigarette smoke to include TSNAs, metals (including lead and cadmium), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (Goniewicz et al., 2018).

Electronic Cigarettes (E-Cigs)

Historically, most warnings against smoking have centered on the dangers of tar and CO found in conventional cigarettes. While the overall rate of cigarette smoking has declined, U.S. youth are increasingly experimenting with alternative tobacco products, especially e-cigs. According to a report released by the U.S. Surgeon General, the use of e-cigs (vaping) increased by 900% among high school students between 2011 and 2015 and, since 2014, has become the most used form of tobacco among youth (CDC, 2023c; HHS, 2016). E-cigs are sold in nearly 8,000 flavors—including cotton candy, apple pie, and gummy bear—to attract younger users. While the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs stated in their 2014 report that e-cigs were substantially less harmful than combustible (traditional) cigarettes, their stance was based on a lack of evidence. Their statement on the reduced harms of e-cigs ignited a media frenzy, spawning the increased use of e-cigs, especially among youth (Nutt et al., 2014). Shortly after the publication of this report, additional research disputed their findings and revealed the devastating health consequences of e-cigs. The FDA started regulating ENDS in August of 2016 with the "Deeming Rule," which gave them the authority over all tobacco products, including ENDS (FDA, 2024b).

E-cigs consist of a reservoir for liquid and a heating element (atomizer) that creates an aerosol from the liquid. The fluid is composed of a solvent (typically vegetable glycerin or propylene glycol) and, in addition to added flavors, has various concentrations of nicotine (FDA, 2024b). In addition to utilizing different materials and copious heating coils, e-cig devices can currently attain a power output that exceeds the 2014 models by up to 20 times. This higher power increases the harm of e-cigs by generating more aerosol and exposing users to more nicotine and other toxicants. Furthermore, modern e-cigs increase bystander exposure (secondhand smoke) to their harmful aerosol components as users exhale more of the aerosol. Even at room temperature, the liquids in e-cigs can be unstable, producing irritating acetal compounds and carcinogens (Eissenberg et al., 2019). According to a review from the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), vaping is associated with significant cardiac changes related to chronic CVD. People who use e-cigs have higher risks of heart attack, stroke, and circulatory problems than those who do not use them (Vindhyal et al., 2019).

In 2018, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) published a report on the public health consequences of e-cigs. They cited the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009, which states that all products introduced after February 15, 2007, must be shown to have a net positive health impact on both users and the community. Their expert panel concluded that while the vapor from e-cigs produced fewer and lower levels of toxicants than CTPs, the overall benefit-to-harm ratio would be determined by three factors: the effect of e-cigs on youth initiation of CTPs, the impact of e-cigs on adult cessation rates of CTPs, and their intrinsic toxicity. Among youth and young adults, the reported use of e-cigs is now significantly higher than the reported use of CTPs. The report cited an increase in e-cig use from 2011 to 2015, with a potential stabilization/decrease in 2016. Further current evidence evaluating the effect of inhaled tobacco products allows for the following conclusive findings (Nabavizadeh et al., 2022; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al., 2018).

- Vascular endothelial function (flow-mediated dilation [FMD]) was not dependent on nicotine, but higher nicotine levels did increase levels of impairment.

- Findings did not support any particular vascular benefits from reduced nicotine products.

- FMD impairment is found with all inhaled tobacco products (including e-cigs).

Nicotine Dependence

More than two-thirds of smokers report a desire to quit, and thousands attempt to stop every day. In 2018, 55.1% (21.5 million) of adult cigarette smokers tried to quit during the past year, and 7.5% (2.9 million) were successful (CDC, 2021, 2022b). According to the HHS (2020), most individuals who try to quit eventually succeed, as 3 in 5 adults who have ever smoked have quit. Since 2002, there have been more former smokers than current smokers (HHS, 2020). Due to its highly addictive nature, nicotine is responsible for many failed cessation attempts, and most users make multiple attempts before they stop permanently.

Nicotine dependence occurs when someone needs the nicotine, as their body has become accustomed to having the substance. Nicotine dependence has physiological and behavioral mechanisms. Nicotine produces a temporary increase in endorphins within the brain's reward circuits, eliciting a slight, brief period of euphoria. It increases levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain, reinforcing the behavior of taking the substance. It also temporarily bolsters aspects of cognition, such as improving a person’s attention span. For people who use tobacco, the long-term brain changes induced by continual nicotine exposure lead to substance use disorder. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) defines addiction as compulsive drug-seeking and use, even in the face of adverse health consequences. Dependence involves unpleasant withdrawal symptoms when tobacco is withheld, such as irritability, cravings, depression, anxiety, cognitive and attention deficits, sleep disturbances, and increased appetite. Furthermore, withdrawal symptoms can begin within a few hours after the last cigarette, making it harder to sustain the desire to quit. Nicotine may make the brain more susceptible to substance use disorder by boosting dopamine concentrations and “prime” the brain for other dependencies. However, research in this area is ongoing (NIDA, 2022; Prochaska & Benowitz, 2019).

Benefits of Quitting

According to the HHS (2020), smoking cessation is beneficial at all ages because it improves overall health, dramatically reduces the risk of developing smoking-related diseases and improves quality of life. The CDC, HHS, and other anti-smoking organizations have generated various public campaigns and educational programs on the benefits of smoking cessation (CDC, 2022b; HHS, 2020). The health benefits of quitting start nearly immediately and extend for decades. See Table 2 for an overview of the time-sensitive health benefits of smoking cessation (CDC, 2022b, 2024a; HHS, 2020).

Table 2

Health Benefits of Quitting Smoking

- Within minutes of quitting, the heart rate drops.

|

- By 24 hours after quitting, the nicotine blood levels drop to zero.

|

- Within several days after quitting, the CO blood level decreases to the level of a nonsmoker.

|

- Within 1 month to 1 year after quitting, shortness of breath and coughing decrease.

|

- From 1 to 2 years after quitting, heart attack risk sharply drops.

|

- From 3 to 6 years after quitting, coronary heart disease risk drops additionally by half.

|

- From 5 to 10 years after quitting, the added risk of cancers of the throat, mouth, and voice box drops by half, and stroke risk decreases.

|

- 10 to 15 years after quitting, additional lung cancer risk drops by half. Further decrease of bladder, esophagus, and kidney cancers is noted.

|

- At 15 years after quitting, the coronary heart disease risk decreases to almost that of a nonsmoker.

|

- By 20 years after quitting, the risk of mouth, throat, and voice box cancers decreases almost to the level of a nonsmoker.

|

(CDC, 2024a)

According to the HHS (2020), quitting smoking reduces premature death, can add up to a decade to a person’s life expectancy, and reduces the risk of numerous adverse health effects, including CVD, COPD, and at least 12 types of cancer. Furthermore, quitting smoking reduces the financial burden on the health care system and society (CDC, 2024a; HHS, 2020).

Treatment Options for Tobacco Dependence

While multiple evidence-based treatment options are available for tobacco dependence, the HHS (2020) has shown they are widely underutilized. Fewer than 1 in 3 adults who try to quit smoking have used proven cessation treatments. The HHS (2020) highlights the need for coordinated action at the clinical, system, and population levels to increase access to treatment. Since tobacco dependence has behavioral (the habit of using tobacco) and physiological (tobacco dependence) roots, effective treatment should address both aspects. According to a 2019 systematic review conducted by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), there is strong evidence that various pharmacologic and behavioral interventions (individually and in combination) effectively contribute to smoking cessation for adults. The review also noted that among pregnant women, behavioral interventions are adequate since there is a lack of evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of pharmacologic therapies in this population (Patnode et al., 2019). The HHS (2020) has endorsed smoking cessation interventions as successful and cost-effective, promoting behavioral treatments such as individual, group, internet-based, and telephone counseling, as well as seven pharmacotherapies approved by the FDA (American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP], 2019; FDA, 2024b).

Behavioral Approaches

Many studies have demonstrated that various behavioral counseling and medication interventions increase smoking cessation compared with self-help materials or no treatment. There are several behavioral support resources for patients who want to quit using tobacco. Combined with ongoing monitoring, support, and treatment, referring patients to Quitline (1-800-QUIT-NOW) or another cessation resource can improve their chances of quitting. Quitline is a free and confidential telephone-based support staffed by trained counselors available across the U.S. Internet-based support systems connect patients to others struggling with tobacco dependence and offer cessation-related links and resources for more information. Federally funded text messaging programs can help patients looking for on-demand encouragement, positive reinforcement, and real-time support. Over recent years, there has also been an influx of smartphone apps that offer ongoing and easily accessible support (CDC, 2021, 2024e).

According to the American Psychological Association (2023), psychotherapy can be utilized to enhance a patient's capacity to make behavioral changes (such as smoking cessation). Types of psychotherapy with demonstrated efficacy in treating tobacco use and nicotine dependence include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). CBT is among the most well-cited and established forms of psychotherapy, as it has the most evidence supporting its clinical utility. The overarching features of CBT include short-term, problem-focused intervention that employs both cognitive and behavioral techniques. CBT teaches patients to restructure cognitive distortions and self-defeating behaviors and replace them with more accurate thoughts and functional behaviors. The focus is narrowed to the patient's current problem(s) to provide practical solutions and strategies to manage them successfully (David et al., 2018). In CBT, patients learn to reframe negative or self-defeating thoughts, making it easier to cope with cravings and unpleasant emotions associated with quitting, including withdrawal symptoms. Thus, CBT treatments may increase the likelihood of successful smoking cessation (GoodTherapy, 2020).

ACT is an action-oriented, process-based intervention that promotes mindfulness techniques to achieve psychological flexibility and help patients live more authentic lives. Psychological flexibility refers to being present, remaining open-minded, and acting consistently with core beliefs. ACT encourages patients to develop a new and positive relationship with their underlying cognitions. Patients learn the consequences of avoiding, denying, and suppressing their inner emotions. By recognizing these challenges and accepting their feelings as appropriate responses to life events, patients learn to behave in ways consistent with their values. ACT encourages patients to acknowledge unwanted emotional experiences as unavoidable aspects of life and forgo viewing them as problems or symptoms. It promotes acceptance of circumstances as they come without attempting to change inevitable things (Rostami et al., 2022). For example, ACT encourages patients to recognize and accept their urges to smoke, with the understanding that these sensations are temporary and will dwindle over time. ACT principles are employed by various smoking-cessation smartphone apps to help smokers achieve enhanced psychological flexibility through education, practice, and committed action (GoodTherapy, 2020; HHS, 2020).

The HHS (2020) reviewed the available behavioral interventions for smoking cessation and found sufficient evidence to conclude that behavioral counseling and cessation medications (see next section) are independently effective in increasing smoking cessation but even more effective when combined. Furthermore, the HHS found sufficient evidence supporting Quitline's counseling services' clinical usefulness and efficacy when provided alone or in combination with medications. In addition, text messaging services are practical and effective mechanisms for improving success rates, especially if they are interactive or offer personalized text responses. Finally, HHS (2020) has also supported the value of internet-based behavioral interventions to enhance smoking cessation, stating that they can be more effective when they contain behavioral change techniques and interactive mechanisms for each person.

For a detailed account of the various types of psychotherapies and their clinical utility, refer to the Psychotherapy NursingCE course.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT)

NRT was first introduced in the late 1970s to assist smokers with gradually weaning off nicotine, the most physically addicting component of cigarettes. Nicotine undergoes first-pass metabolism, which limits the effectiveness of orally ingested formulations. Therefore, NRT options available over the counter (OTC) in the U.S. include patches, gum, and lozenges. Nasal sprays and inhalers are also available but require a prescription from a licensed prescriber (See Table 3) (American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP], 2019).

Table 3

NRT Formulations

OTC Options | Prescription Only |

Type | Gum or Lozenge | Transdermal Patch | Nasal Spray | Inhaler |

Adverse Effects | - Unpleasant taste

- Mouth and throat irritation

- Hiccups

- Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (dyspepsia, nausea, flatulence)

- Jaw soreness

- Due to the rapid release of nicotine, adverse effects are often experienced if chewing the lozenge or if incorrectly chewing the gum, including:

- Lightheadedness

- Dizziness

- Nausea/vomiting

- Increased mouth/throat irritation

| - Skin reactions, such as erythema, pruritus, and burning

- Sleep disturbances, such as abnormal or vivid dreams or insomnia

| - Nasal/

- throat irritation

- Ocular irritation, such as tearing

- Sneezing

- Coughing

| - Mouth/ throat irritation

- Dry cough

- Hiccups

- GI effects, such as dyspepsia or nausea

|

(AAFP, 2019)

NRT has been shown to improve smoking cessation rates by 50% to 70%. Combined therapy (using two or more NRT products, such as a patch and gum) is more effective than monotherapy. The transdermal patch is the slowest and longest-acting option, with serum concentrations peaking in 6 to 8 hours. Most reported adverse effects (see Table 3) improve quickly once the patch is removed. The gum, lozenge, and inhaler formulations peak in 20 to 60 minutes. The nasal spray offers the fastest onset of action, peaking in the central nervous system (CNS) within 5 to 20 minutes. This most closely mimics the effects of smoking a cigarette. Most NRTs are recommended for use for up to 3 months (except the oral inhaler, which may be used for up to 6 months), as prolonged use increases the risk of throat and nose irritation. APRNs should counsel patients not to abruptly discontinue NRTs. They should be tapered before stopping (AAFP, 2019; Prochaska & Benowitz, 2019; Sealock & Sharma, 2023). NRT was shown statistically to improve abstinence rates among smokers compared to placebo in the EAGLES trial. In this large, randomized trial of adult smokers, the bupropion and NRT group showed superior abstinence rates compared to the placebo group (Evins et al., 2019; FDA, 2022).

Cunningham and colleagues (2016) mailed nicotine patches to 500 adults in Canada who smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day and compared their self-reported abstinence rates to 499 smokers who did not receive patches. The study group reported a 7.6% abstinence rate, while the control group reported 3% at 30 days. Saliva samples were also requested to validate abstinence, but only half of the study participants returned samples, and only 14 samples (2.8%) could be confirmed negative. Interestingly, while 421 of the 500 participants in this study reported receiving the patches, only 246 reported using them. Furthermore, only 46 reported using all patches at the 8-week follow-up point (Cunningham et al., 2016). In a randomized trial involving 657 adult smokers in New Zealand, nicotine patches resulted in a quit rate of 5.8% in that group and 7.3% when combined with e-cigs. In addition, when NRT was studied in pregnant women, its use resulted in decreased smoking in the second trimester and better child development outcomes at 2 years (Dinakar & O’Connor, 2016). Efforts to help people quit smoking are ongoing, but the outcomes have not been particularly effective, and there has been no substantial improvement in recent years. A Cochrane review (2021) of 81 randomized controlled trials that included over 112,000 participants found moderate-certainty level evidence that counseling, cost-free smoking cessation medications, and tailored smoking cessation print materials may increase rates of smoking cessation in primary care practices. Combination methods have been found in some studies to be the most effective for smoking cessation, with quit rates from 8% to over 20%. The Cochrane review concluded that more research is needed to determine which combinations are most effective (Lindson et al., 2021; Sealock & Sharma, 2023).

Pharmaceuticals

Bupropion sustained-release (SR) and varenicline are FDA-approved prescription medications for smoking cessation. Bupropion SR is an atypical antidepressant that primarily functions as a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It was developed to treat depression since it helps improve concentration and focus and reduce hyperactivity. It was also found to have nicotinic receptor-blocking activity. It has been shown to double smoking cessation rates in short-term studies versus placebo, with slightly less efficacy than NRT. Bupropion SR improved abstinence rates among smokers compared to placebo in the EAGLES trial, with 22.6% and 16.2% abstinence rates at 12 and 24 weeks, respectively, compared to 12.5% and 9.4% in the placebo group (Evins et al., 2019). The most reported adverse effects include insomnia, dry mouth, headaches, nausea, anxiety, agitation, increased motor activity, tremors, and tics. Patients should be advised to avoid taking bupropion SR at bedtime to minimize insomnia. Prescribing guidelines recommend a dosing schedule of 150 mg PO daily for 3 days, followed by 150 mg PO BID. The dose should not exceed 300 mg per day, and patients should be counseled to allow at least 8 hours between twice-daily doses. Bupropion SR should be started 1 to 2 weeks before the target quit date (TQD). The duration of therapy is typically 7 to 12 weeks, but maintenance therapy can continue for up to 6 months in some patients. Dose tapering is not necessary when discontinuing treatment. The medication carries a 0.1% risk of seizures and, therefore, is contraindicated in patients who have underlying seizure disorders and should not be given to patients who have a history of stroke, brain tumor, brain surgery, or traumatic brain injury. Additional contraindications include a current or prior diagnosis of bulimia or anorexia nervosa, simultaneous abrupt discontinuation of alcohol or sedatives/benzodiazepines, and current or recent (in the previous 14 days) monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) use. APRNs should perform a complete medication reconciliation before prescribing bupropion to ensure patients are not taking other medications known to lower the seizure threshold (AAFP, 2019).

Varenicline works by blocking nicotine receptors in the brain. As a partial agonist, it binds selectively to alpha-2 beta-4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, inhibiting dopaminergic activation produced by smoking to decrease cravings and withdrawal symptoms. It is more effective than bupropion SR, roughly as effective as NRT, and has been shown to have a lesser risk of withdrawal symptoms when compared to other medications (HHS, 2020; Singh & Saadabadi, 2022). The most common adverse effects include nausea, insomnia, vivid dreams, headaches, constipation, vomiting, flatulence, and xerostomia, with increased adverse effects reported when used in combination with NRT. APRNs should counsel patients to take varenicline with a full glass of water after eating in order to decrease GI upset. Sleepwalking, agitation, and drowsiness have been reported. Some observational studies have demonstrated an increase in neuropsychological symptoms or exacerbations of previously existing psychiatric illness and suicidal behavior, as well as an increased rate of cardiovascular events (AAFP, 2019; Singh & Saadabadi, 2022). However, the FDA-mandated EAGLES trial showed no statistically significant increase in moderate-to-severe neuropsychological adverse events for patients taking varenicline versus placebo. The study’s findings also revealed a statistically significant improvement in abstinence rates with varenicline at 12 and 24 weeks (33.5% and 21.8%, respectively) compared to all other groups (Evins et al., 2019).

In a previous study, varenicline was compared with an NRT patch as well as a combination of a patch and a lozenge. After 12 initial weeks of treatment, the study showed no significant difference in sustained abstinence at follow-up at 26 weeks. The varenicline group did report more adverse effects than the NRT group, such as abnormal dreams, insomnia, nausea, sleepiness, constipation, and indigestion (Baker et al., 2016). The American Thoracic Society concluded in 2020 that varenicline is more effective than bupropion or nicotine patches with similar or less adverse effects. Additional benefits have been noted with combination therapy, including varenicline and nicotine patches. Studies have shown there are also significant benefits to extending treatment beyond 12 weeks in comparison to shorter durations of treatment (Leone et al., 2020).

Varenicline should only be prescribed to patients 18 years and older. Prescribing guidelines recommend the following dosing schedule.

- Days 1 to 3: 0.5 mg PO daily

- Days 4 to 7: 0.5 mg PO BID

- Weeks 2 to 12: 1 mg PO BID (AAFP, 2019)

Ideally, varenicline should be started a week before the TQD, and the duration of therapy is typically 12 weeks. An additional 12-week course may be given to some patients. Patients may initiate treatment up to 35 days before their TQD. Alternatively, patients may reduce smoking over 12 weeks of therapy before quitting altogether and continue treatment for an additional 12 weeks. A maximum dose of 0.5 mg twice daily is advised for patients who have renal impairment (creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min/1.73m2) since this medication can cause renal failure and kidney stones. For patients who have end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on hemodialysis, a maximum dose of 0.5 mg once daily is recommended (AAFP, 2019; Singh & Saadabadi, 2022).

Although not approved in the U.S., cytisine has been available in the UK since January 2024 and has been safely used in Eastern Europe and many other countries for smoking cessation since the 1960s, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2024). Cytisine is a partial agonist of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha-4 beta-2 and is primarily derived from the Cytisus laburnum plant. Clinical trials have demonstrated promising results, linking cytisine to an increased likelihood of smoking cessation as a practical, low-cost medication option. The rationale for its lack of approval in the U.S. is unclear, but critics blame its generic structure and pharmaceutical market exclusivity as the primary obstacles. Cytisine is considered a highly promising aid for quitting smoking due to its affordability and quick action. However, its limited availability and research within the U.S. are likely attributed to the minimal financial motivation for companies to invest in the expensive regulatory approval process there (Gotti & Clementi, 2021; Tutka et al., 2019).

E-Cigs and Smoking Cessation

E-cigs, while initially thought to offer some advantage over NRT and other methods for quitting smoking, are not endorsed by the FDA as a cessation tool. This stance is due to emerging evidence of their negative health impacts, as highlighted by the CDC and recent shifts in research focus (FDA, 2024a). Despite this, research is conflicting. For instance, a study in 2024 (Auer et al.) involving 1,246 smokers found that those who used e-cigarettes in combination with standard cessation counseling were more likely to abstain completely from tobacco and nicotine after 6 months (33.7%) compared to those who did not use e-cigarettes (20.1%). Additionally, a comprehensive meta-analysis in 2023 (Lindson et al.) indicated that e-cigarettes helped 14 out of 100 smokers quit long-term, which is more than double the rate of those who did not use any cessation aids. However, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) in 2018 reported only limited evidence supporting e-cigarettes as an effective smoking cessation aid. Despite some individual studies suggesting benefits, the overall safety and efficacy of e-cigarettes remain unproven (Auer et al., 2024). The general consensus among U.S. health care professionals is that the potential risks of e-cigs overshadow their benefits, especially considering the lack of rigorous studies identifying their long-term effects. Public health officials, pediatricians, and parents express significant concern over the rising e-cigarette use among young people and the uncertain long-term consequences (Lindson et al., 2023; Prochaska & Benowitz, 2019).

Other Alternatives

Some have proposed that smoking rates in the U.S. could be drastically reduced with legislative action. Various groups have proposed federal harm taxes based on a similar system in Sweden, in which all tobacco products are taxed based on their relative harm. Others have proposed federal regulations regarding the amount of nicotine that manufacturers of cigarettes can include in their products. One study used a simulation model based on the opinions of eight experts to predict the public health effects of such a federal regulation on cigarettes. It concluded that initiation rates would steadily drop as cessation rates increased. Only 1.4% of the country will be smoking cigarettes by 2060, and the rate of tobacco use will gradually decrease to 11.6% by 2060. They predicted that 16 million would-be smokers would be spared by 2060, 33 million by 2100, and 8.5 million tobacco-related deaths would be avoided by 2100 (Apelberg et al., 2018). HHS (2024) has proposed a national framework for furthering smoking cessation efforts based on four major principles: advancing health equity; community engagement; coordination, collaboration, and integration; and evidence-based approaches. These population-level strategies, including pricing increases, harm taxes, comprehensive smoke-free policies, and nationwide mass media campaigns, have been shown to increase and support smoking cessation in the U.S. (HHS, 2024).

Additional cessation treatments have also been explored. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of mindfulness meditation looked at 10 randomized trials and found no statistically significant effect on abstinence rates or the number of cigarettes per day (Maglione et al., 2017). A similar study looked at financial incentives compared to e-cigs or NRT. Over 6,000 adult smokers were randomized to one of four groups: free NRT or pharmaceuticals with secondary e-cigs (if desired), free e-cigs, or two different financial incentive programs (reward versus deposit) for smoking cessation. Both financial incentive groups were also offered free NRT or pharmaceuticals with a secondary free e-cig (if desired). The results showed only 80 confirmed cases of abstinence. Abstinence rates were significantly higher in the financial incentive groups (2% and 2.9%) versus the usual-care group (0.1%) (Halpern et al., 2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis including 22 studies looking at the effectiveness of financial incentives on smoking cessation showed that financial incentives are particularly beneficial in specific groups of people, including those who have unmet financial needs, those who are pregnant or recent postpartum, or those who respond well to external rewards or whose threshold is high for behavior change (Siersbaek et al., 2024).

The APRN's Role in Smoking Cessation

According to the HHS (2020), 4 out of every 9 adult cigarette smokers who saw a health care professional did not receive smoking cessation advice during the past year. Even brief advice to quit (typically under 3 minutes) from a clinician improves cessation rates and is highly cost-effective. APRNs have a responsibility to educate patients on the health consequences of tobacco use and the health benefits of quitting. APRNs working with children and adolescents should offer preventative counseling, as preventing tobacco use among youth is critical to ending the tobacco epidemic. APRNs should integrate cessation discussions and interventions into patient encounters where appropriate, as they are well-positioned to facilitate increased access to treatments. Through environments that encourage patients to quit smoking and interventions that make quitting easier, patients are more likely to be receptive to information and take their health care provider’s concerns seriously (HHS, 2020).

References

Allen, M. S. & Tostes, R. C. (2023). Cigarette smoking and erectile dysfunction: An updated review with a focus on pathophysiology, e-cigarettes, and smoking cessation. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 11(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/sxmrev/qeac007

American Academy of Family Physicians. (2019). Pharmacologic product guide: FDA-approved medications for smoking cessation. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/tobacco/pharmacologic-guide.pdf

American Cancer Society. (2020). Health risks of smoking tobacco. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/tobacco/health-risks-of-tobacco/health-risks-of-smoking-tobacco.html

American Lung Association. (2023). What’s in a cigarette? https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/smoking-facts/whats-in-a-cigarette

American Psychological Association. (2023). Understanding psychotherapy and how it works. https://www.apa.org/topics/psychotherapy/understanding

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Health effects of cigarettes: Cardiovascular disease. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/cigarettes-and-cardiovascular-disease.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022a). Smoking and tobacco use: Costs and expenditures. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/cost-and-expenditures.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022b). Smoking cessation: Fast facts. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/cessation/smoking-cessation-fast-facts/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023a). Burden of cigarette use in the U.S. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/resources/data/cigarette-smoking-in-united-states.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023b). Current cigarette smoking among adults In the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm#nation

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023c). Youth and tobacco use. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/tobacco_use/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). Benefits of quitting smoking. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/benefits-of-quitting.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). Health effects of cigarette smoking. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#smoking-death

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). Health problems caused by secondhand smoke. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/secondhand-smoke/health.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024d). Trends and disparities in secondhand smoke. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/secondhand-smoke/disparities.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024e). Quitlines and other cessation support resources. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/hcp/patient-care/quitlines-and-other-resources.html

David, D., Cristea, I., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

Dinakar, C. & O’Connor, G. T. (2016). The health effects of electronic cigarettes. New England

Journal of Medicine, 375(14), 1372–1381. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1502466

Eissenberg, T., Bhatnagar, A., Chapman, S., Jordt, S., Shihadeh, A., & Soule, E. K. (2019). Invalidity of an oft-cited estimate of the relative harms of electronic cigarettes. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 161–162. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305424

Evins, A. E., Benowitz, N. L., West, R., Russ, C., McRae, T., Lawrence, D., Krishen, A., St Aubin, L., Maravic, M. C., & Anthenelli, R. M. (2019). Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders in the EAGLES trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 39(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001015

Goniewicz, M. L., Smith, D. M., Edwards, K. C., Blount, B. C., Caldwell, K. L., Feng, J., Wang, L., Christensen, C., Ambrose, B., Borek, N., van Bemmel, D., Konkel, K., Erives, G., Stanton, C. A., Lambert, E., Kimmel, H. L., Hatsukami, D., Hecht, S. S., Niaura, R. S., Travers, M., Lawrence, C., & Hyland, A. J. (2018). Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Network Open, 1(8), e185937. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5937

GoodTherapy. (2020). Smoking cessation. https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/issues/smoking-cessation

Gotti, C. & Clementi, F. (2021). Cytisine and cytisine derivatives. More than smoking cessation aids. Pharmacological Research, 170, 105700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105700

Institute of Medicine; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; & Committee on Reducing Tobacco Use: Strategies, Barriers, and Consequences. (2007). Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. (Bonnie, R. J., Stratton, K., & Wallace, R. B., Ed.) The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11795

Li, M., Koide, K., Tanaka, M., Kiya, M., & Okamoto, R. (2021). Factors associated with nursing interventions for smoking cessation: A narrative review. Nursing reports, 11(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11010007

McMurtrey, J. E. (n.d.). Tobacco. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/plant/common-tobacco

Nabavizadeh, P., Liu, J., Rao, P., Ibrahim, S., Han, D. D., Derakhshandeh, R., Qiu, H., Wang, X., Glantz, S. A., Schick, S. F., & Springer, M. L. (2022). Impairment of endothelial function by cigarette smoke is not caused by a specific smoke constituent, but by vagal input from the airway. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 42(11), 1324–1332. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.318051

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; & Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. (2018). Public health consequences of e-cigarettes: Consensus study report. (Stratton, K., Kwan, L. Y., & Eaton, D. L., Eds.). The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24952

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2022). Tobacco, nicotine, and e-cigarettes research report: Is nicotine addictive? https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/tobacco-nicotine-e-cigarettes/nicotine-addictive

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2024). 2024 exceptional surveillance of tobacco: Preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence (NICE guideline NG209). National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK602607/

Nutt, D. J., Phillips, L. D., Balfour, D., Curran, H. V., Dockrell, M., Foulds, J., Fagerstrom, K., Letlape, K., Milton, A., Polosa, R., Ramsey, J., & Sweanor, D. (2014). Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the MCDA approach. European Addiction Research, 20(5), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360220

Patnode, C. D., Henderson, J. T., Coppola, E. L., Melnikow, J., Durbin, S., & Thomas, R. G. (2019). Interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventative services task force. JAMA, 325(3), 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.23541

Prochaska, J. J. & Benowitz, N. L. (2019). Current advances in research in treatment and recovery: Nicotine addiction. Science Advances, 5(10), eaay9763. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay9763

Rodriguez, D. (2024). Cigarette and tobacco products in pregnancy: Impact on pregnancy and the neonate. UpToDate. Retrieved May 31, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cigarette-and-tobacco-products-in-pregnancy-impact-on-pregnancy-and-the-neonate

Rostami, M., Moheban, F., Davoudi, M., Heshmati, K., & Taheri, A. A. (2022). Current status and future trends of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for smoking cessation: A narrative review with specific attention to technology-based interventions. Addiction & Health, 14(3), 229–238. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9743826/

Sealock, T. & Sharma, S. (2023). Smoking cessation. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482442/

Singh, D. & Saadabadi, A. (2022). Varenicline. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534846/

Tutka, P., Vinnikov, D., Courtney, R. J., & Benowitz, N. L. (2019). Cytisine for nicotine addiction treatment: A review of pharmacology, therapeutics and an update of clinical trial evidence for smoking cessation. Addiction, 114(11), 1951–1969. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14721

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health consequences of smoking- 50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). E-cigarette use among young and young adults: A report of the surgeon general. https://article.images.consumerreports.org/prod/content/dam/consumerist/2016/12/2016_sgr_full_report_non-508.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Smoking cessation: A report of the surgeon general: Executive summary. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-executive-summary.pdf

U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2022). Want to quit smoking? FDA-approved and FDA-cleared cessation products can help. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/want-quit-smoking-fda-approved-and-fda-cleared-cessation-products-can-help

U. S. Food & Drug Administration (2024a). E-cigarettes, vapes, and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/e-cigarettes-vapes-and-other-electronic-nicotine-delivery-systems-ends

U. S. Food & Drug Administration (2024b). Resources for professionals about vaping & e-cigarettes: A toolkit for working with youth. Center for Tobacco Products. https://digitalmedia.hhs.gov/tobacco/hosted/Vaping-ECigarettes-Youth-Toolkit.pdf

Vindhyal, M. R., Ndunda, P., Munguti, C., Vindhyal, S., & Okut, H. (2019). Impact of cardiovascular outcomes among e-cigarette users: A review from national health interview surveys. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 73(9), 11. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(19)33773-8

World Health Organization. (2023). Tobacco. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco